A colour film, published on YouTube, courtesy of the Canada-based Museum of Estonians Abroad depicts Estonian towns and people in the 1930s.

The film, made in 1938 and 1939, shows the Estonian towns of Tallinn, Tartu and Narva as well as the Estonian folk and singing culture just few years prior to losing the country’s independence to the Soviet Union.

Although the period of authoritarian rule during those years was a low point in the Estonian democracy, economically the country had recovered from the Great Depression and was doing very well by the standards of its time.

In fact, a well-known Estonian historian and Tallinn University researcher, Jaak Valge, has said that Estonians were better off in the 1930s in comparison to the rest of the continent, that they are today.

“If the current Estonia is more than two times poorer than Finland, then before World War II Finland was just a quarter wealthier. While Portugal is presently richer than Estonia, Estonians were far more wealthy in the 1930s than the Portuguese,” Valge told the Estonian Television in 2013 (however, the Estonia’s GDP per capita is about equal with Portugal as of 2016 – editor).

Judging by this film, the people looked happy, energetic and cheerful, indeed.

Estonia in interwar period

After becoming an independent nation in 1918 and signing the Tartu Peace Treaty with Russia in 1920, Estonia’s first constitution was promulgated, establishing a parliamentary system. Next year, the country became a member of the League of Nations.

With a political system in place, the new Estonian government immediately began the job of rebuilding. As one of its first major acts, the government carried out an extensive land reform, giving tracts to small farmers and veterans of the War of Independence. The large estates of the Baltic German nobility were expropriated, breaking its centuries-old power as a class.

At first, agriculture dominated the country’s economy. Thanks to land reform, the number of small farms doubled to more than 125,000. Although many homesteads were small, the expansion of landownership helped stimulate new production after the war.

Land reform, however, did not solve all of Estonia’s early problems. Estonian agriculture and industry (mostly textiles and machine manufacturing) had depended heavily on the Russian market. Independence and Soviet communism closed that outlet by 1924, and the economy had to reorient itself quickly toward the West, to which the country also owed significant war debts.

The economy began to grow again by the late 1920s, but suffered another setback during the Great Depression, which hit Estonia during 1931-34. By the late 1930s, however, the industrial sector was expanding anew, at an average annual rate of 14 per cent. Industry employed some 38,000 workers by 1938.

Independent Estonia’s early political system was characterised by instability and frequent government turnovers. The political parties were fragmented and were about evenly divided between the left and right wings.

The first Estonian constitution required parliamentary approval of all major acts taken by the prime minister and his government. The Riigikogu (State Assembly, the Estonian parliament) could dismiss the government at any time, without incurring sanctions. Consequently, from 1918 to 1933 a total of twenty-three governments held office (in comparison, in 25 years since regaining independence in 1991, just 14 governments have held office).

The country’s first big political challenge came in 1924 during an attempted communist takeover. In the depths of a nationwide economic crisis, leaders of the Estonian Communist Party, in close contact with Communist International leaders from Moscow, believed the time was ripe for a workers’ revolution to mirror that of the Soviet Union.

On the morning of 1 December 1924, some 300 party activists moved to take over key government outposts in Tallinn, while expecting workers in the capital to rise up behind them. The effort soon failed, however, and the government quickly regained control. In the aftermath, Estonian political unity got a strong boost, while the communists lost all credibility. Relations with the Soviet Union, which had helped instigate the coup, deteriorated sharply.

The era of Silence

By the early 1930s, Estonia’s political system, still governed by the imbalanced constitution, again began to show signs of instability. As in many other European countries at the time, pressure was mounting for a stronger system of government. Several constitutional changes were proposed, the most radical being put forth by the protofascist League of Independence War Veterans.

In a 1933 referendum, the league spearheaded replacement of the parliamentary system with a presidential form of government and laid the groundwork for an April 1934 presidential election, which it expected to win.

Alarmed by the prospect of a league victory and possible fascist rule, the caretaker prime minister, Konstantin Päts, organised a pre-emptive coup d’état on 12 March 1934. In concert with the army, Päts began a rule by decree that endured virtually without interruption until 1940. He suspended the parliament and all political parties, and he disbanded the League of Independence War Veterans, arresting several hundred of its leaders.

The subsequent “Era of Silence” was initially supported by most of Estonian political society. After the threat from the league was neutralised, however, calls for a return to parliamentary democracy resurfaced. In 1936, Päts initiated a tentative liberalisation with the election of a constituent assembly and the adoption of a new constitution. During elections for a new parliament, however, political parties remained suspended, except for Päts’s own National Front, and civil liberties were only slowly restored. Päts was elected president by the new parliament in 1938.

Losing independence

Although the period of authoritarian rule that lasted from 1934 to 1940 was a low point in Estonian democracy, in perspective its severity clearly would be tempered by the long Soviet era soon to follow. The clouds over Estonia and its independence began to gather in August 1939, when Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact (also known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact), dividing Eastern Europe into spheres of influence.

Moving to capitalise on its side of the deal, the Soviet Union soon began to pressure Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania into signing the Pact of Defence and Mutual Assistance, which would allow Moscow to station 25,000 troops in Estonia.

President Päts, in weakening health and with little outside support, acceded to every Soviet demand. In June 1940, Soviet forces completely occupied the country, alleging that Estonia had “violated” the terms of the mutual assistance treaty.

With rapid political manoeuvring, the regime of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin then forced the installation of a pro-Soviet government and called for new parliamentary elections in July. The Estonian Communist Party, which had only recently re-emerged from underground with fewer than 150 members, organised the sole list of candidates permitted to run. Päts and other Estonian political leaders meanwhile were quietly deported to the Soviet Union or murdered.

With the country occupied and under total control, the communists’ “official” electoral victory on 17-18 June with 92.8 per cent of the vote was merely window dressing. On 21 July, the new parliament declared Estonia a Soviet republic and “requested” admission into the Soviet Union. In Moscow, the Supreme Soviet granted the request on 6 August 1940. The independent Estonia was finished.

Very interesting movie. Clearly shows Estonia’s success between two World wars.

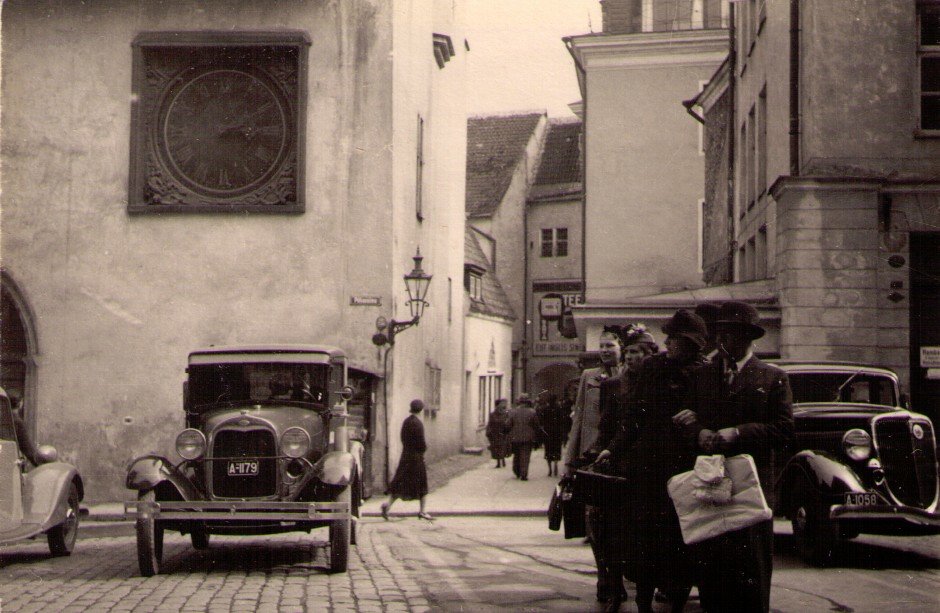

The picture of the old clock is one of the ones my great grandfather Ernst von Stackelberg took in 1938.

This clock is very beautiful. It is good to know your information about this!

Very middle class take on life in Eesti .Not everyone could afford to go to Pirita to hang out at the beach restaurant The people in the countryside lived very poor lives, in primitive conditions which had not improved in 100 years. As for the “Vaikiv Ajastu” , as Päts saw he was not going to hold on to power, he fomented a coup d’etat to prevent Kindral Larka being elected.This included having one of his opponents ,Sirk, being defenestrated in Luxemburg.Would a democratically elected Vapsid government have been better for the country than a Päts-Laidoner dictatorship? I think Probably.

What Stalin did to our people, and the people of the once free countries in that part of the world was one of the biggest crime ever perpetrated on humanity in the history of the world & should not ever be forgotten. I am the grandson of Adam Matteus, and I am fully aware of our great history. The true history of the great Estonian people, going back to 1,000 BC. The world needs to know the truth about just what the communist & Stalin did to both our country & it’s people. I am very proud of just how far we have come since we became a free country once more. I only wish there were more films about Estonia in the past. Many people do not understand or know what we fought with the Germans against the Russians in WWII. They must understand that there is good & bad no matter where you go or who you wish to talk about, yes there were some bad Germans, but there were far more good Gremans & they knew what the spread of communism would do to this world. We need to be proud of what we did. Keep up the good work you are doing, and “Thank You”