What do the world’s oldest continually living cultures, i.e. those of the Australian indigenous people and Estonians, have in common? At first glance not much, but at a closer look at their respective cultural history, we can surprisingly find many similarities.

Although the recorded Aboriginal history traces back at least 50,000 years and the Estonian one “only” 5,000, both have traditionally lived from the land and have a very close connection to it. Nature guides them both. In Aboriginal Australia, it is the whole life philosophy or the Dreamtime that is the foundation of all; in Estonia it used to be the nature god Taara and being connected to the land.

Similarily, the history of displacement and foreign people taking over their land, is what both Aboriginal people and Estonians have in common.

One of the most fascinating spheres that reveals the aboriginal world view is their art. Australian Aboriginal art is among the oldest art movements in the world. But art should not be separated from the rest of the aboriginal philosophy since it is just a part of it.

When we look at a Western painting, often there is no right or wrong answer and different interpretations may be welcomed. In case of an aboriginal painting, however, specific knowledge of the tribal members would be needed to fully understand the work. There is almost always an outside story for the public and an inside story that only the initiated tribe members would understand.

An artist called Jimmy Robertson Jampijinpa has said: “Our tribal members look at our paintings and they can read them. They know where things began and ended, and which place is holy. The Europeans have to look onto the paper and read from the book what the artwork is, they do not read from a painting. They only look at the patterns.”

Aboriginal art is not created for aesthetic purposes. It is rather a natural process to describe the surroundings and pass on the stories of Dreaming. Art has a strong didactic meaning.

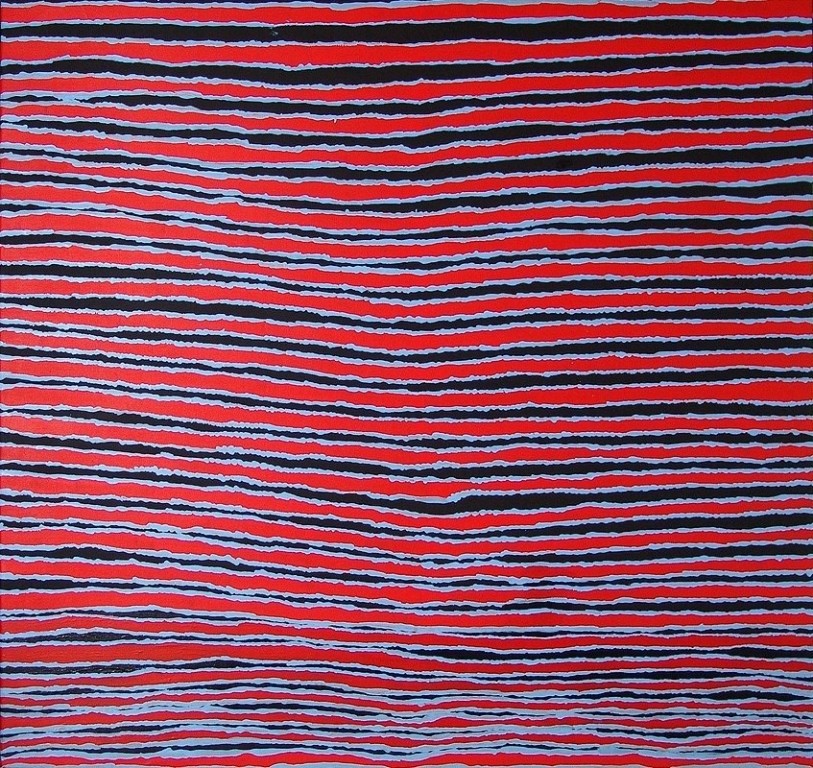

The most common technique used on Aboriginal paintings are dots. Historically, they would cover a secret subject or represent the desert environment which looks dotted from high above due to its grass tufts. Lines are also common and they usually represent sand dunes in the desert. In addition, a myriad of different but often repeating symbols are used, such as concentric circles, half circles or animal prints. The meaning of these differs in different regions and tribes. The artworks are tied to the specific place where they were created, the images are often from a bird’s perspective – and paintings can be viewed as maps of the country.

Aboriginal art is characterised by a complex set of rules. Some works are meant to be viewed by initiated men only, some are for women to see, and only a part of the created artworks are for the public.

But if Aboriginal art is such a multi-faceted complex world of hidden meanings and historical secrets, how would a person from a non-Aboriginal background feel to be involved in it?

Di Stevens, who runs an art gallery dedicated to indigenous art, Tali Gallery in Sydney, explains that the art is aesthetically beautiful and contemporary, yet holds traditional stories that are 40,000 years old. She says that she is passionate about it because it never ceases to amaze her. The extraordinary diversity of Aboriginal art makes her realise that the more one learns about it, the more one realises how little one knows about it.

Stevens also points out that the people at the Tali Gallery have found that indigenous art is a highly successful medium to create a profound and impactful understanding of Aboriginal cultural traditions among non-indigenous Australians in a more general sense. Artwork also conveys evidence of living cultural practices still to be found. Its diversity shows that Indigenous Australians are not a homogeneous culture. The paintings and crafts can hold the key to generating respect as well as a far greater appreciation of this complex and cleverly structured civilisation which is the longest living continuous culture in the world that should be widely revered.

I

Paintings by Alice Nampitjinpa. Nampitjinpa’s all three paintings are called “Sandhills” – and to an Estonian viewer they look distinctly like the stripes of our folk skirts. Alice Nampitjinpa comes from Haasts Bluff, Northern Territory, Australia.