Members of the European Union are emphasising the need for the free movement of data across the bloc, and at the eve of the Estonian presidency of the EU Council, the country is trying to start the processes that could eventually lead to it becoming reality.

In February 2016, the then-president of Estonia, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, gave a speech to the European Parliament in Strasbourg where he proposed an idea that had been talked about by Estonian officials before, but at the time seemed like impossibility – a fifth freedom of the European Union, the free movement of data between the members of the bloc.

A year later, more and more people are emphasising the need to make this a reality, and now, at the eve of the Estonian presidency of the EU Council, the country will make efforts to start the process that could eventually lead to the point where no country can impose restrictive measures to the free flow of data across member states’ borders.

In his speech a year ago, Ilves gave a much-publicised example of how it was easier to ship a bottle of olive oil from Sicily to the Arctic Circle than to send an iTunes song across a border. In a later interview, he explained his thoughts further, saying that he was unable to buy an iTunes album for his Latvian wife because he had an Estonian iTunes account. And while that example might have something to do with the cross-border data movement policies of Apple, a US company, he did make a valid point. Why is something so elementary this complicated in the digital sphere, where no physical obstacles exist?

Removing the restrictions

Of course, this was just an example, or as former president Ilves himself puts it, “the most understandable example for the largest number of people”. The problem, he told Estonian World, is within the European Union, because the movement of data in itself is, at least as of now, within the hands of every member state’s national data protection agency who decide each on their own, which data can cross borders and which can’t.

“My position has, for years, been that the problem is not technology, but policy, regulation and legislation,” Ilves says. This means the EU should send a signal that it is an open environment for business and competition – by removing the restrictions of the analogue world that inhibit free flow of data among the member states.

Although regulations are enablers for this, the mind-set also has to change – data is an asset that should be shared and transmitted across borders, however, not forgetting the rules on the protection of the rights of the individuals. By that, Estonia wishes to emphasise the importance of creating the right kind of regulatory conditions for the cross-border data exchange that would create more competition, jobs, products and services.

Of course, agreeing to such rules between member states at the EU level is not an easy task. However, with the advances in technology like the Internet of Things, 3D printing and autonomous cars, more and more data will be machine-generated and this data is the raw material of the information society we live in. This topic needs an EU-level approach and Estonia wishes to share its expertise in the digital field and make digital advances we have here a reality across the EU.

Influence to the entire European Union

“The Single Market Act, or the legislation to create a single market, also demanded that every country would change its own internal laws,” Ilves explains. “This is the case every time a pan-European law is passed – countries’ laws need to be changed so that they wouldn’t contradict.”

But even though a year has passed since president Ilves publicly proposed the fifth freedom of the EU, not much has happened. Some discussions have started on whether we need a legal act at the EU level in order to remove unjustified data localisation requirements. And one of the country’s priorities during its six-month presidency in the second half of 2017 is to start the process that would eventually lead to free movement of data becoming reality.

Margus Mägi, an advisor on digital policy at the Government Office of Estonia, an organisation with the mission to support the government and the prime minister in policy drafting and implementation, and also tasked with organising Estonia’s 100th birthday celebration, points out that the ideas and proposals Estonia can make during its presidency have a longer term effect than the presidency itself.

“The free movement of data is a subject that influences entire Europe,” he points out. “It influences almost every aspect of life, but it’s time-consuming and difficult, but not impossible, to come to the ‘one size fits all’ solution.”

Focus on the synergy between privacy and technology

One of the issues the countries have to tackle is the fact that more and more devices are becoming “smart” – they are connected to the internet and they are generating data. This raises a lot of complex issues. “For example, to whom belongs the data created by a smart fridge, concerning the information what people have in their fridge and when was the last time they went shopping?” Mägi brings out an issue. “How is this information used? Is that personal data that has very concrete rules, or is it a different type of data that the manufacturers can use as they please? And if so, should the manufacturers be the sole parties that decide how this data is used?”

According to Mägi, the free movement of personal data has been discussed in the EU for a long time. Back in 1995, the EU passed a data protection directive where one of the objectives was the free movement of personal data. “Of course, the current legislation talks about personal data, but today we’re more and more coming to the realisation that in addition to personal data there might be other data that isn’t associated with a specific person and therefore aren’t, legally, personal data,” he describes. “For example, the statistics of public transport, the aggregated information about people’s purchasing behaviour, data generated by the sensors in a car, etc.”

But how exactly can Estonia influence the processes that would lead to the free movement of data becoming a reality? “We live in a developed digital society, we use different technological solutions every day and, understandably, we’d like to use them all over Europe,” Mägi says.

“During our presidency, we will definitely rely on our expertise to provide potential ways forward for the EU in its goals to achieve the free movement of non-personal data like in case of personal data. The premise is that besides personal data that can move freely in case of certain safeguards are applied, there should be a coherent and clear set of rules that enable the free movement of data that is not of personal nature. ”

The whole of Europe is interested

Estonia is a digital pioneer not only in the EU, but all over the world. Estonians vote online, do their taxes online, sign documents with a click of a mouse with their digital ID-cards, and also purchase prescription medicine via digital prescription, or e-prescription. These are all things that an average Estonian takes for granted when communicating with the government.

However, in most of the member states in the EU, things are not that rosy. Let’s not forget that in some countries, people still use bank cheques, albeit less and less. So how is it possible to make all the “old European” countries that are so set in their ways to accept this new reality of the digital age and create policy that would pave the way to the truly free movement of data across borders?

“The free movement of data is a general principle; its realisation is about regulations and agreements.” So first, the EU member states will have to discuss the matter and the potential rules and regulations. “This is what we will try, during our presidency, to accelerate and find solutions together.”

“To make the free movement of data truly a reality in the EU, there are many solutions,” Mägi says. “One of the positions is that we need a regulation that would eliminate the cross-border data movement barriers set by the member states, which would mean free movement of data within the entire territory of the EU. Others find, however, that we don’t need a separate regulation and these barriers will have to be eliminated on sector by sector basis.”

Good news

There is some good news there, too. According to Mägi, by 2018, the data protection legislation in all European Union countries is almost identical. This puts one very important rule regarding personal data in place. “Of course, it would be naive to say that creating unified rules for non-personal data is easy – but through negotiations it’s possible to reach a solution that pleases all parties.”

“Right now, the time is right to move on with the issue of free movement of data,” the government advisor says. “We’ve agreed on personal data, now we can look further from it and deal with the data that is not of personal nature.”

Another bit of good news is that the movement of at least certain data already works between Estonia and Finland. By 2018, the e-prescription system will cross the borders of the two nations, making it possible for Finnish people to buy their medicine in Estonia with a prescription issued in Finland – and vice versa.

Digital IDs are already there

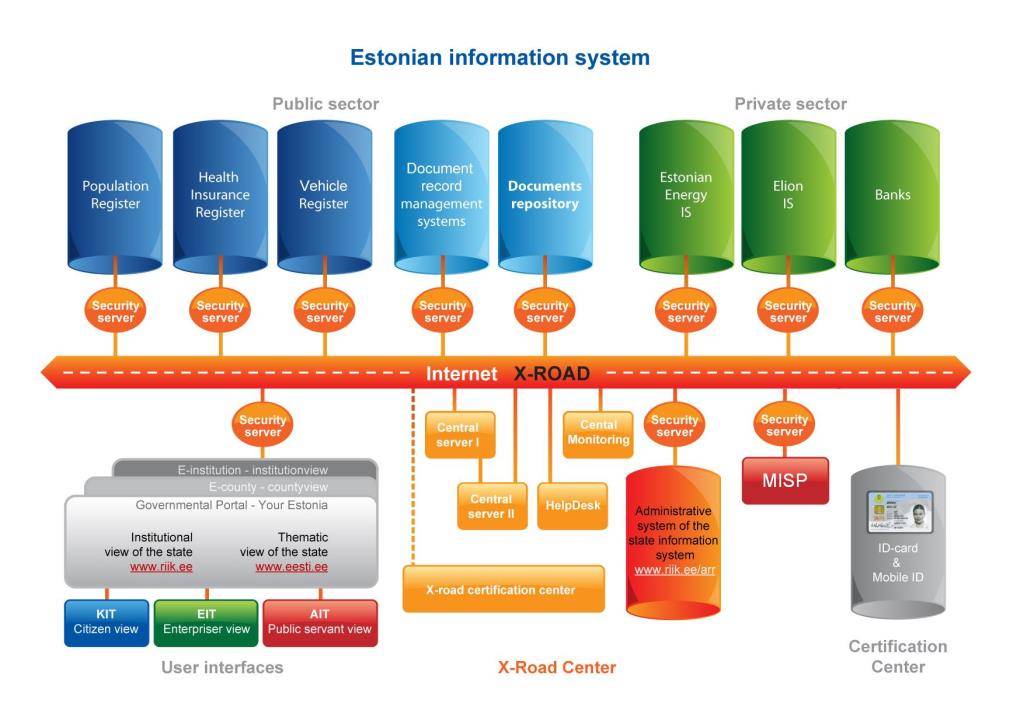

Estonia and Finland have been developing a data exchange platform that is based on the Estonian data exchange layer X-Road. According to Rauno Veri, the chief communications officer at the Estonian Information System authority, Estonia and Finland last year signed the memorandum to connect the Estonian X-Road and its Finnish equivalent, Palveluväylä, by April 2017 at the latest. “Technologically the platform is ready for data exchange, some organisational and legal aspects are still under negotiations,” he says.

For a service like the e-prescription to really work across the borders of the EU member states, these countries also need a digital ID system similar to the Estonian ID-card. Fortunately, this is where the member states have already come to an agreement. In 2014, the EU countries passed the eIDAS regulation that set the rules for accepting the digital signature across the union. The regulation became law in July 2016, and the part of this legal act that deals with the mutual recognition of digital identities will become law in 2018.

So there’s yet another part of some good news – the future ideal of the data actually moving freely across the borders of the European Union might not be that far away.

I

Cover: The digital identity card of Estonia’s e-residents (the image is illustrative.)