Juhan Kuus, the internationally renowned photographer of Estonian descent, was completely unknown in his country of ancestors, but the Estonian public is now becoming aware of his works.

Kuus (1953–2015) may have been one of the greatest photojournalists in South Africa, but his works are practically unknown in Estonia. Now an exhibition at the Adamson-Eric Museum in Tallinn aims to give Kuus and his legacy a worthy place in the cultural scene and in the cultural history of the country of his ancestors.

Scattered Estonian talent

By the end of World War II, more than 90,000 people had left Estonia as refugees. Among them was Juhan Kuus’s father, Harry, who was one of the “Finnish Boys”, young Estonian men who fought for Finland during its defensive war against the occupying Soviet Union. Kuus Sr finally ended up in South Africa via Sweden, and his son, Juhan, was born in his new home country.

Juhan Kuus started to work as a photo reporter at the age of 17, and developed into one of the most influential and radical photographers of the country during his 45-year-long career.

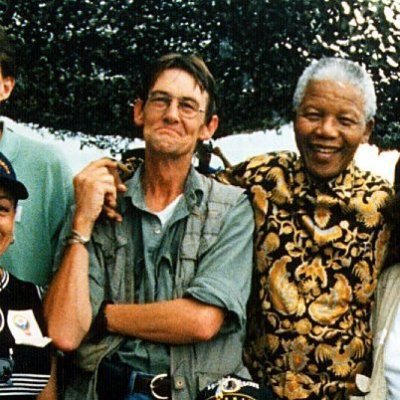

“His photos, which were taken with utter devotion, direct poignancy and unyieldingly close contact to what he was shooting, found their way into the world’s leading newspapers, journals, exhibitions and photo festivals. He received dozens of awards, including South Africa Press Photographer of the Year on several occasions, and is the only photographer of Estonian descent ever to have received the most prestigious press photo award in the world: the World Press Photo Award, which he won twice, in 1978 and 1992,” Kersti Koll, one of the curators behind the exhibition, said.

At the peak of his career, from 1986 to 2000, Kuus worked as the South African correspondent and photojournalist for the Paris and New York editorial offices of the prominent Sipa Press Agency, founded in France in 1973. His works were published in the Times, the Independent, the New York Times, Paris Match, the Los Angeles Times, among others.

An anthropologist-documentarian

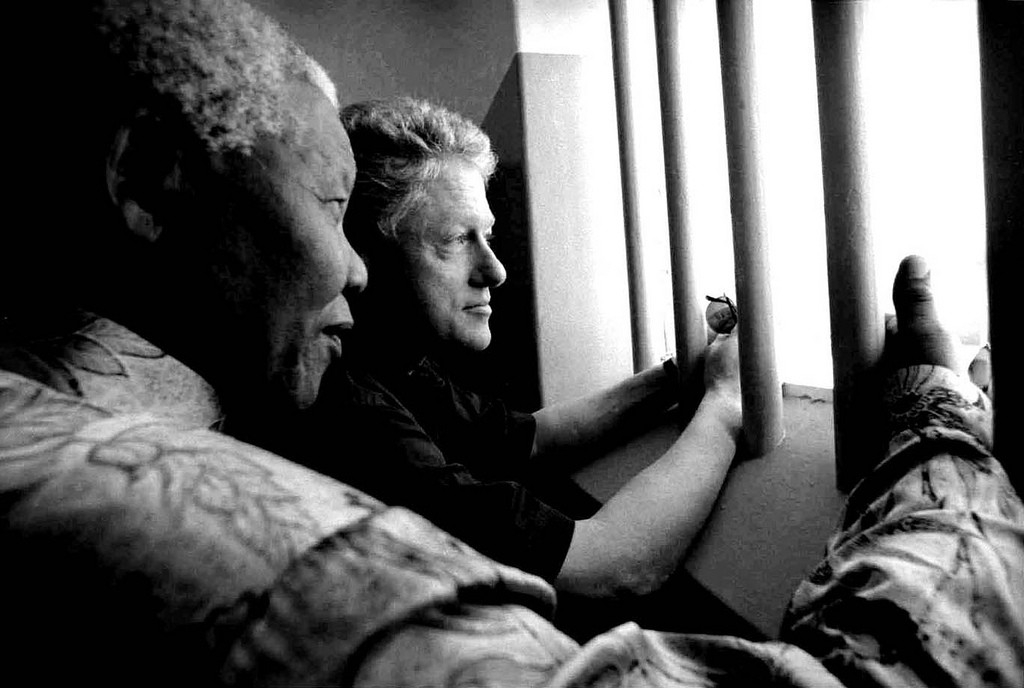

“Throughout his career, Kuus applied his sensitive and sharp eye and complete straightforwardness to record the various aspects of apartheid and the fight against it. He took pictures of the people involved and the events that took place, acquiring the role of an invaluable chronicler of the tumultuous times in South African history,” Koll said.

But according to Koll, his best works are not limited to news photography. “First and foremost, he considered himself to be an anthropologist-documentarian, whose photos narrate deeply humane stories about South African people, regardless of their racial background.”

Kuus’ photos recorded the fighting and brutal violence of the fierce conflicts in his country at the time, which was what the press worldwide was mainly interested in. But his photos also depict the joys and concerns of simple people, their everyday lives and traditions, the relationship between man and land, the prevailing social norms and taboos, and paradoxical situations.

“Kuus was always looking for humaneness and trying to see the reasons behind a person’s behaviour, attitudes and choices. Having seen and recorded every possible aspect of human nature through his camera lens without sparing himself physically or emotionally, he became increasingly interested in the philosophical issue of humaneness, and the possibility or impossibility of being and remaining human,” Koll explained.

Believer in the grander scale of things

Although renowned for his work, Kuus’ destiny took a sad turn in his later life. In one of the tributes – after his death from falling – one of his former colleagues and friends described many episodes from working with Kuus, which included many proud as well as sad moments.

Fearless and single-minded, documenting the world around him was the most important thing in his life and came before anything else. “Despite getting into financial hardship, he never wavered in his belief that what he did was important and, in the grander scale of things, was bigger than himself or any financial discomfort,” his former colleague said.

When his friend wondered why Kuus wouldn’t take on commercial work or shoot weddings on the weekends to help dig himself out of the financial hole, Kuus replied: “Because that type of stuff is trivial. I’ve got more important work to do.”

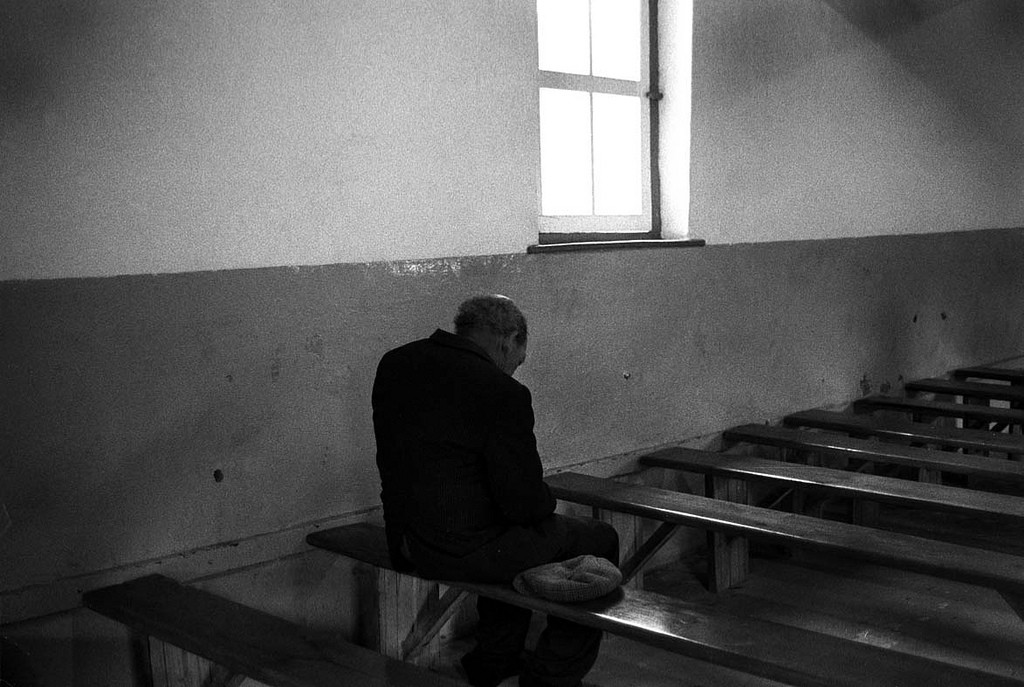

Towards the end of his life, Kuus was completely penniless and homeless, living in a Salvation Army shelter, although his friends supported him. “He focussed on documenting and photographing the lives of the homeless and street-people of Cape Town, who accepted him as one of their own, because he was,” his friend wrote in a tribute.

And while still optimistic and planning new projects, an unfortunate fall from the stairs took this talented life.

His former friends and colleagues hope that Kuus, who signed one of his last emails as “Concerned Humanities and Documentary Photographer”, will be remembered and revered for his great work. The exhibition in Tallinn plays its part to accomplish this.

I

The exhibition is part of the long-term goal of the Art Museum of Estonia and the Adamson-Eric Museum to map the art and culture of Estonians living abroad, and to introduce artists from different generations of our diaspora to audiences in Estonia. Images courtesy of Juhan Kuus. Cover: Himba women in Namibia, 1989 (Juhan Kuus).