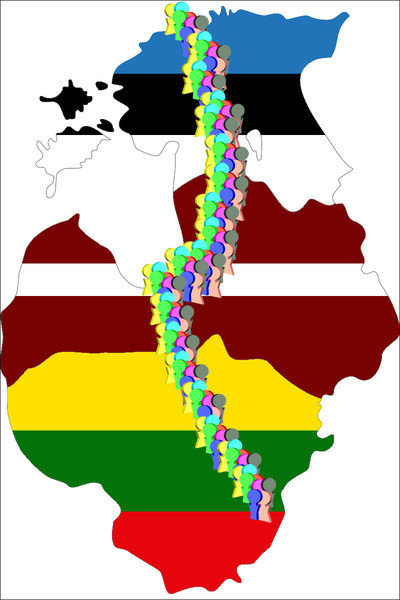

At 19:00 on 23 August 1989, approximately two million people from Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania joined hands, forming a human chain from Tallinn through Riga to Vilnius, spanning 600 kilometres, or 430 miles. It was a peaceful protest against illegal Soviet occupation, and also one of the earliest and longest unbroken human chains in history.*

Prelude to the events

The Baltic Chain, also known as the Baltic Way, was organised in order to draw the world’s attention to the existence of Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact – a treaty signed 50 years prior, on 23 August 1939, between the foreign ministers of the Soviet Union and Germany – Vyacheslav Molotov and Joachim von Ribbentrop.

In the secret protocols that accompanied the treaty of non-aggression, the two totalitarian powers divided Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania in violation of international law into respective spheres of influence, which led to Nazi Germany starting the Second World War on 1 September 1939 with its attack on Poland. The Soviet Union invaded Estonia and Latvia on 16 June 1940.

The pact and its three secret protocols resulted in comprehensive military and economic co-operation between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union from 1939 – 1941. The Soviet Union’s significant political and economic support for Nazi Germany allowed the Nazis to occupy a great part of Europe and begin the widespread persecution in its occupied territories. In turn, Nazi Germany’s support for the Soviet Union made it possible for the Soviets to carry out wide-spread oppression in its occupied territories.

On 22 June 1941, however, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union – until now its partner. Although at the beginning of the Second World War the Soviet Union had been acting in co-operation with the aggressor, in the end of the war it was one of the victors. And the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact essentially remained in effect: the lasting occupation of the Baltic states by the Soviet Union went on.

Although the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and its secret protocols were well-known to democratic Western nations, the Soviet Union denied the existence of secret protocols.

Symbolising the solidarity between the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian people, the Baltic pro-independence movements – Estonian Popular Front, Latvian Tautas Fronte, and Lithuanian Sąjūdis – planned an enormous event to draw global attention by demonstrating a popular desire for independence for each of the countries; and at the same time publicise the illegal Soviet occupation and position the question of Baltic independence not as a political matter, but as a moral issue. The idea for the Baltic Chain was born.

On 23 August 1989, the three nations surprised the world. Approximately two million Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians were taking hold of each other’s hands for fifteen minutes, and jointly demanding recognition of the secret clauses in the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and the re-establishment of the independence of the Baltic States.

People joined hands to create a 600 km long human chain from the foot of Toompea in Tallinn to the foot of the Gediminas Tower in Vilnius, crossing Riga and the River Daugava on its way, creating a synergy in the drive for freedom that united the three countries.

Aftermath

The first reaction from the Soviet authorities was harsh. The statement from the Central Committee of the Communist Party, issued on 26 August 1989 in Moscow, read: “Matters have gone far. There is a serious threat to the fate of the Baltic peoples. People should know the abyss into which they are being pushed by their nationalistic leaders. Should they achieve their goals, the possible consequences could be catastrophic to these nations. A question could arise as to their very existence.“

The pro-independence activists and the public in the Baltic States were concerned, in the light of this statement – could Moscow intervene militarily to crush the national movements, just as the Soviet Union had done in Hungary in 1956, and in Czechoslovakia in 1968?

On 31 August, the Baltic activists issued a joint declaration to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, claiming to be under threat of aggression and asked for an international commission to be sent to monitor the situation.

The US President, George H. W. Bush, and the Chancellor of West Germany, Helmut Kohl, urged the Soviet Union to show restraint, urging peaceful reforms. Faced with an international embarrassment, after four years of so-called perestroika, the Soviet authorities eventually toned down their rhetoric and failed to follow up on any of their threats.

Furthermore, the Soviet Union finally acknowledged the existence of the secret protocols and on 24 December 1989, the Congress of People’s Deputies of the Soviet Union, with a decision entitled “Political and legal assessment of the 1939 Soviet-German non-aggression pact”, declared the secret protocols to the pact to be null and void, and without legal basis.

The Congress stated that the demarcation of the Soviet and German spheres of influence in the pact and other secret protocols signed with Germany between 1939-1941 legally contravened the sovereignty and independence of a number of other countries. With its decision, the Soviet legislature condemned the pact and the signing of other secret agreements with Germany.

Russia, being the legal successor of the Soviet Union, has unfortunately failed to upheld this decision – a matter of concern for Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The Russian government continues to insist that its control of the Baltic states was legal. “There was no occupation. There were agreements at the time with the legitimately elected authorities in the Baltic countries,” declared Sergei Yastrzhembsky, the Kremlin’s European affairs chief, in 2005.

Outcome

The Baltic Chain helped to publicise the Baltic cause around the world and symbolised solidarity among Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The positive image of the non-violent Singing Revolution spread among the Western media.

The national movements used the increased exposure to position the debate over Baltic independence as a moral, and not just political question: reclaiming independence would be restoration of historical justice and liquidation of Stalinism. The pro-independence movements, established in 1988, became more assertive and radical: they shifted from demanding greater freedom from Moscow to full independence – finally achieved on 20 August, 1991.

Remembering the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact as a cautionary example of the agreement made between two totalitarian regimes and its aftermath, on 2 April 2009 the European Parliament approved the resolution “European conscience and totalitarianism”.

The resolution calls on the member states of the European Union to declare 23 August as the European Day of Remembrance for the Victims of all Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes, to be observed with dignity and impartiality. The Estonian Parliament approved its support of the resolution on 18 June 2009 and declared 23 August as Remembrance Day.

Read also: Gallery: The Baltic Way in pictures.

I was there!

What was the feeling being there and being aware you were making history back then? Were you afraid?