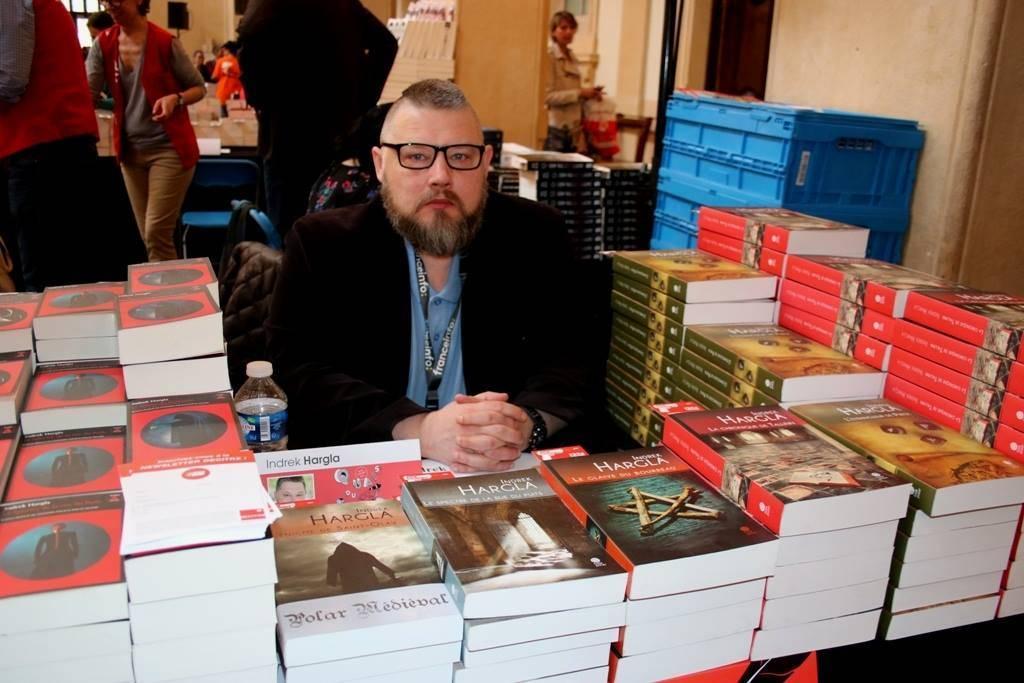

Edith Soosaar interviews one of the best known and best-selling fantasy and fiction writers in Estonia, Indrek Hargla – the author of the popular Apothecary Melchior detective novels – who shares thoughts about his writing process, experience in publishing and translating, and becoming a writer.

Indrek Hargla has written novels, novelettes and short stories. He became famous with the Apothecary Melchior stories (historical crime-fiction set in a medieval Tallinn) of which the first two are translated and available in English. Over the years his works have been translated into French, English, German, Hungarian, Latvian and Finnish. His books are available to order from the Book Depository, (yes, this is affiliate link and these are good books).

I would like to know more about your writing process. Do you plan out the story before you start writing or start from the beginning with a vague outline and see where the characters take you?

I use both methods; writing must be an adventure and disciplined craftsmanship at the same time. You should always have certain ideas what you want to write but sometimes you don’t need to stick to original plans, the story and characters come alive and guide you. The genre is important; in crime fiction, the genre dictates the structure, disposition of characters and events. Crime and science fiction readers have certain expectations and writer must fulfill them, play by the rules but be original and innovative.

I do a lot of outlining when I write Melchior novels. Crime fiction always involves “engineering” – you just cannot kill somebody and see what happens and who might be the killer. I must know from the first sentence who did it and why. Then again, outlining and research must be minimal; a writer must not be enslaved to outlining. Usually, when you have written about one-third of any text, it is a right time to read it over and assess what kind of thing it wants to be, where it goes, what is the soul and spirit inside it; what it needs to succeed.

The thing is, you do not know your characters before writing. They develop and start to live on their own, listen to them, argue with them but try to understand them.

You have emphasised in your previous interviews the importance of the writer’s voice. How long did it take for you to get comfortable with your own writer’s voice? What would you recommend for young authors to develop theirs?

About 10-15 years I guess, and I am still not very comfortable with my own voice, but I am getting there.

The most important thing I recommend: do not write your story as you’d think this kind of story is usually written. In your mind, you imagine a certain way of style and choice of words how writing generally goes, and you try to replicate, to mirror this. That is the wrong way, this way you get very average, ordinary, a mediocre blend of a very usual literature – a kind of second-hand derivative stuff.

There is no other way but to meditate, work hard, concentrate really hard. You must write as you write and not how you think it is usually written but not overdo it, not to be too original, postmodern or challenging or too cool. About 70% of excellent writing is standard, common to all good literature – clear storytelling, colourful characters, sharp ideas, eloquent and powerful style. If it is not in you, then it’s not in you. When the real you is a bad writer, you have to face it and try not to write anymore.

How do you discipline yourself through the writing and multiple editing rounds? Do you use the Pomodoro technique (20-minute writing, 10-minute break) or some other time control-technique?

I do not use any specific technique. I just work, contemplate, meditate, plan, research and plan again whenever I can, and this is how it is most of the time. I may sit behind the computer for five hours and not write a single sentence – and then suddenly write three pages in one go. I think four or five pages of quality text per day is enough and one cannot demand more.

How do you decide on the genre for a new book? Have you had a case where you started writing with an idea in your head, but the story didn’t work, and you had to change something really fundamental (like a genre, location etc) to make it work?

No, you cannot change the genre. Novelettes can grow into novellas and novellas into novels, yes – but genres do not change. Maybe sub-genres can – what you originally planned as a steampunk-themed, may turn into more science fantasy, but no more. When you start a crime novel and cannot stick to the rules of the genre you probably end up with a boring mainstream book nobody wants to read.

Once I started a novel and after a while, I felt I am not up to it. I put it aside for a few years and then suddenly realised that the main idea was still there and still good – so I thought why not to write a short story? And I did; I transformed the idea of a novel into a story, or a novelette rather, and I am still satisfied with it. “Raudhammas” (The Iron Tooth – editor) is the name of the novelette; people still remember it and it was broadcasted on national radio.

What do you consider your weakest point/downfall as a writer? What’s your strongest side? What is the hardest part about being a writer? What’s the best part?

Weakest point? Impatience maybe. I am lazy enough to be a writer, but you have to be lazier. You write a sentence or a chapter; you know it’s not perfect, but it is passable, and you think: fine, let it be. There is always a better choice of words, which comes with more meditation and concentration.

The strongest side? A wish not to write ordinary stuff that has been written so many times before. The hardest part is the realisation that writing is not easy. It takes so much from you – time and energy – so basically, you give something away. The best part is this miraculous feeling when you see that suddenly things are falling into right places. You have put some ideas and elements into the story and you do not know why… And then you see it, everything fits like someone has been guiding you.

Do you find it harder to come up with positive or negative characters?

Positive ones, probably. Positive characters tend to be very much the same and ordinary. You need to give them some bad traits, make them from good characters into chaotic good ones, or so.

Being a writer seems to be an ever-learning process. What are the things you feel you still need to master? What is the most useful skill you have learned to help you along with your career? Both as a person writing books as well as helping your books reach the audience?

Ever-learning, yes. As I said, there is always a better choice of words. I have learned not to use common expressions in fiction. I learned there are words that a more loaded, suggestive, thought-provoking and full of possibilities than others and you need to find them. If you cannot write a good dialogue between two characters, then do not write that scene. You must always put interesting and unexpected things into every scene. Do not deliver empty scenes.

It takes much more time to come up with interesting ideas and that’s why I am such a slow writer. But I feel I must not give anything away.

Apothecary Melchior stories

Two of your books from Apothecary Melchior murder mysteries have been translated into English. Did you search for translation–publishing options yourself or was its initiative from the publishing house?

No, I never do that, I do not search for options myself. In fact, I cannot even remember now how the first two books got published in English. French and Finnish translations are much more important to me.

The Melchior series gets better all the time if I’m allowed to say this. The fifth and sixth novel really stands up for me and I am very happy that they are published in French. Jean Pascal Ollivry, my translator, was this wonderful person who once took the initiative to recommend the Melchior series to the French publisher.

It’s not uncommon to add a character flaw or a handicap to the protagonists to make them more humane and balances as humans. In Melchior’s case, you choose to add his health condition. What other options did you consider when first building his character?

I cannot really say I considered any other options. I just came up with the idea when I wrote and inserted it into the story not knowing what I am going to do with it or how important it was going to be, if ever. It just felt like a right or interesting thing at the time.

In later books, I picked it up and started playing around. Writing is like this – you just sit alone, come up with things and hope somebody takes interest in reading it. Melchior’s curse was not a product of careful engineering, just a spark of an idea that I used, in hope it would help make the character more interesting.

How did you come up with the Melchior’s health condition? Did you had a specific condition in mind or is it made up for the story?

It is made up. Mostly. But the reasons behind it and the true essence are not yet revealed so I cannot say anything more.

Do you control the story, do the stories take over as you write or is it a joint effort?

They must take over. They must come alive and guide me, they must tell me what they want. But writing a crime novel is an “engineering” to a large extent. There are certain rules and you must be disciplined to follow them. There have to be suspense and surprise ending in crime fiction; you have to deceive your readers, but you cannot cheat.

There can be a love story in crime novel but it can’t be a romance novel as a whole. You can use an element of horror or thriller, make them organically part of the story, but you must not lose focus and concentrate on a murder mystery. Murder must have the central role and prevail over other storylines. The crime novel is meticulously crafted, constructed and engineered product but it must look effortless.

Publishing home and abroad

Tell us about your very first novel manuscript? How long it took to write, how many rewrite rounds? When you had a manuscript ready how did you go about finding a publisher?

My first novel, “Baiita needus” (The Curse of Baiita – editor), is a very badly written novel. I wrote it quickly, I seem to remember. It was written by an aspirant of literature. I sent it to a local novel competition. Eventually, unfortunately, it got some honourable mentioning there, so one publisher approached me and bought it. I do not want to be remembered for that novel. Estonia is that small that even raw material like this gets published.

Do you participate in the marketing of your books abroad? How? The London Book Fair? Festivals? Books signings?

I do when I am asked. I do not market anything on my own. When I am invited to a festival, I go. I was not invited to the London Book Fair. Mostly, I have been to France for different fairs and festivals.

How is the marketing of books for the international audience different from marketing in Estonia?

Well, nobody knows anything about the Estonian literature abroad, so it must be very tough for a foreign publisher to publish an Estonian novel. I do not think that any Estonian author would ever be sold at airport book stands. You must be an Anglo-American or Scandinavian author to be really promoted in the international market.

Despite being one of the best known, bestselling and widely read Estonian author, you have chosen not to be a member of the Estonian Literature Association. Why?

I left the association before the last elections. Some members from the board were recruited to a certain left-wing, pro-Soviet party, and started intensely to use their membership in literature association to promote left-wing politics under the red flags. Most of the supporters of this party do not even speak the Estonian language. It felt like the association was hijacked by Soviets, so I chose to give up my membership.

I do not think that you can be a member of the board and speak in the name of all association to promulgate ideas that are against the principals that form the core of Estonian statehood.

Who in your opinion is currently the best writer in Estonia and in the world?

I do not know about the world. In Estonia, I could name three – or two, rather – because Rein Põder recently passed away, probably the best novelist of all times in Estonia. The other two are Meelis Friedenthal and Andrus Kivirähk.

In your Q&A session at the Estonian Opinion Festival 2015 at Rahva Raamat’s (Estonian book retailer) garden you said Estonia already had plenty of “looking-out-the window-and-telling-what-you-see” books and Estonian literature could use some more fiction writing. Do you feel the situation has improved since?

Not much. Realism and writing about yourself and every-day life are the main paradigm of Estonian literature. Those who dare to venture away from that mainstream do not write well yet.

Asimov or Adams?

Asimov!