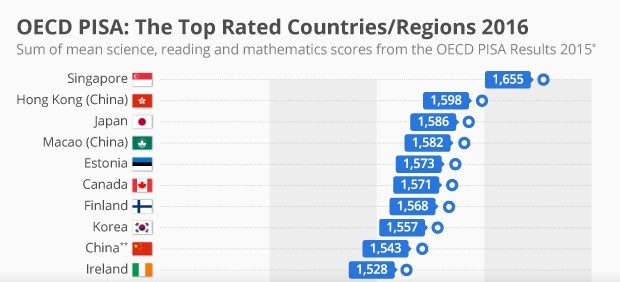

According to the PISA tests, the results of Estonian 15-year-olds are the best in Europe and among the strongest in the entire world. But what is the recipe for this success and what could be improved upon?

It is rather difficult to objectively measure how good the Estonian education system is, but one of the ways is an international survey conducted on the OECD’s (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) initiative that aims to evaluate education systems worldwide – the PISA tests.

These tests are held once in every three years to test the skills and knowledge of 15-year-old students. Pupils from randomly selected schools take tests in functional reading, mathematics and science. The skills of Estonia’s basic school students rank among the best in the world and at the absolute top in Europe. Every time Estonia has participated in the tests (2006, 2009, 2012), the results have improved.

The number of top achievers, who can solve extremely complicated tasks, is higher than ever before – standing at 13.5 per cent, while the OECD average is eight. Among the European countries, Estonia has the smallest number of low performers – over twice as little compared with other countries’ averages.

As Estonian World finds out from the schoolchildren and teachers, the recipe for success in the Estonian basic education system consists of motivated students, hard-working and professional teachers and supporting homes. Although the success tastes sweet, there is still a lack of one ingredient – joy – and this is the real challenge for Estonia. Luckily, many people are already working on different projects to bring the joy back to children.

Equal opportunities

Three 15-year-old boys from Saku, a borough near Tallinn – Edvin Kabanen, Aron Pill and Johann Adamberg – attend 8th grade at Saku Gymnasium. They are happy that teachers have given them marks from the first grade. “It has developed our sense of duty, but at the same time, we have always known that if we fail a test, we can do it again,” Kabanen explains.

Kadre Lahtmets graduated from Tartu Hugo Treffner Gymnasium in the summer of 2016. She has also studied at Nõo Elementary School and Tartu Mart Reinik School.

According to her experiences in different schools, she says that in Estonia, education is one of the first priorities for the adolescents – and pupils work hard for better results already in the elementary school.

“I have learned that if the larger part of the class is motivated to study, then it also makes those students work harder who might not be as motivated – because they do not want to have worse results than anyone else. It creates a good learning environment, where everybody motivates each other,” she explains. At the same time, Lahtmets notes that more support could be given to the laggards.

Lotta and Märten Josh Peedimaa – sister and brother, both studying at Tartu Miina Härma Gymnasium, (Lotta in 11th and Märten Josh in 9th grade) – say that the reason for good PISA results lie in intensified teaching that is offered to more talented or enthusiastic pupils. Lotta Peedimaa also underlines equal opportunities – a chance for everyone to prove themselves – as one of the key factors of basic education success in Estonia.

Maie Kitsing, an external evaluation adviser at the Estonian ministry of education and research and Estonia’s representative in the OECD PISA council, agrees with Peedimaa’s opinion and says the Estonian education policy has always been driven by principle of comprehensive school. “All children and adolescents must have equal access to the education, no matter where they live or how wealthy their parents are,” Kitsing explains.

She adds that this is evident in the PISA results – in Estonia, the kids’ background plays a smaller role than in most other countries in the world.

The society helps value education

According to Jaan Reinson, the principal of Tartu Descartes’ School, the results show the elementary schools meet their challenges head-on – both the content (curricula) and the organisational side (a presence of qualified teachers) are strong. “Also, we do not have educational stratification – so the system works,” he says.

Both Kitsing and Reinson note that the reason derives from the society – people in Estonia value education highly and the majority of the parents encourage their children to take learning seriously.

Comprehensive school means there is one national curriculum framework and all pupils study accordingly, Kitsing explains. Moreover, the education policy has always placed a lot of emphasis on creating equal opportunities and need-based funding of educational resources – in order to implement appropriate supporting measures for pupils with educational special needs.

Kitsing also points out that one of the reasons for good results is the autonomy given to teachers and schools. “On a national level, we have agreed on the basic results a schoolchild has to achieve, but every school and teacher can decide it by themselves on how to reach these goals,” she says and adds that the high demand on teaching profession assure the reliability of the teachers.

Enough room for development

But what worries principal Jaan Reinson is the lack of joy at schools. Although the PISA results are excellent, pupils and teachers do not feel happy.

Eighth graders Edvin Kabanen, Aron Pill and Johann Adamberg admit that if a pupil has a great sense of duty, they can be pretty stressed out when, for example, seven tests are waiting in a row in a week. “Teachers give us a lot of homework. On one hand, it is good – it helps remember and understand new material, but on the other hand – we are overloaded with all the tasks,” Pill says.

Adamberg adds that this causes the situation where children show great results, but are not exactly jolly. Kabanen suggests that at least the weekends could be for resting and without homework.

Reinson argues that the overloaded curricula could be reduced in the volume and become more vital. “We face a great challenge to increase schoolchildren’s physical activity again and to create up-to-date schools,” he says. “Material resources are important here, but not only – human resources ought to be well-looked after as well.”

Maie Kitsing mentions that to keep up with good results and to solve the bottlenecks, it is important to use the resources thoughtfully, improve the reputation of the teacher profession and to support consistently the professionalism of the pedagogues. “We have to ensure that the school could hold the pace of the changing world,” she concludes.

Jubilee celebrations help bring joy to schools

In 2018, the Republic of Estonia celebrates its 100th birthday and everyone can show initiative and create something as a gift to Estonia and its people. As the children and adolescents are one of the main focus groups, the Estonia 100 organising committee hopes the projects aimed at schoolchildren help make the school environment and atmosphere friendlier and happier – so that the school joy of Estonian pupils could be as high as the results in the knowledge test.

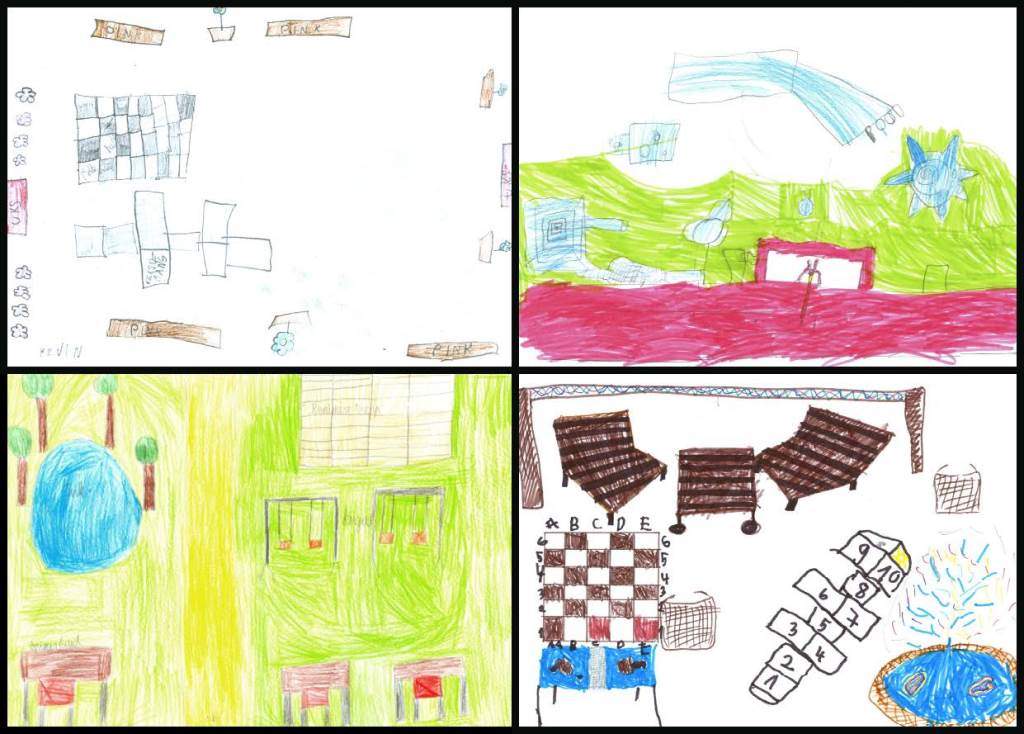

For example, NGO Estonian Green School Grounds has initiated the pilot project, “Children to Play and Learn in School Grounds!”, with an aim to increase and improve outdoor learning and play facilities. “This is a way to get children away from the smartphone screens and to encourage them to move around, play and be more active outside,” Siiri Treufeld, the head of the NGO, explains.

One of the 15 schools participating in the pilot project is Albu Elementary School. Maie Rambi, the principal of the school, says they want the school ground to be more attractive to the children so they would choose to spend their leisure time in fresh air. “We want to improve outside learning possibilities, maybe to create some nature tracks,” she explains.

Rambi is also planning to involve the local government, parents and community. “We already had a great brainstorming, where all children and school personal could either write down or make a drawing of their wishes – now we are analysing which ideas to select,” she says.

Fresh air, physical activity and digital solutions together

Keeping children and adolescents at least a bit away from the screens and make them forget possible school stress seem to be key factor for many people who want to give a gift for Estonia.

One of the initiatives is a project called “Estonia’s 100 oaks”. There is at least one school in every county that already grows small oaks that they are going to plant to the local parks in 2018.

In a somewhat similar attempt, the Natural History Museum and the botanical garden of the University of Tartu strive to send children out to the forests and grassland to collect Estonian plants.

Muraste School, on the other hand, invites all the other schools to dance during the breaks. Aule Kikas, a project leader, tells that in Muraste children really love those breaks. “They completely lose themselves to the dance – they dance the tensions away,” she says.

This being a forward-looking society, however, there are also projects that plan to educate children about the topics in the digital world.

One of them involves introducing dedicated “smart classes” in every school – an idea by Birgy Lorenz from the Estonian Informatics Teachers Association. She says it is so compelling to see how the smart devices are used in other schools and to share the ideas with each other.

“We have a group on Facebook and 25% of Estonian schools have already joined in. It is absolutely amazing how thanks to ICT, it is possible to weave with other subjects,” Lorenz says. For example, at Haljala Gymnasium, a computer programme is used for digital embroidery.

These projects play their part ensuring that the school joy of Estonian pupils could be as good as the results in the knowledge test.

Cover: Schoolchildren starting the Gustav Adolf Grammar School in Tallinn. Photo by Kristjan Salum. * This article was originally published on 9 February 2017.

Interesting data, their should be more policy towards copying the success of better educational programs.