As Estonians around the world are gathering to cheer for their homeland and celebrate the country’s independence day on 24 February, it’s appropriate to recall how the independent country was born, the independence maintained, lost and restored again.

A quest for independence

Starting with the Northern Crusades, Estonia became a battleground of foreign powers from the 13th century onwards. Denmark, Germany, Russia, Sweden and Poland fought their many wars over controlling the important geographical position as a gateway between the East and the West.

Being first conquered by Danes and Germans in 1227, Estonia was subsequently ruled by Denmark, by Baltic German ecclesiastical states of the Holy Roman Empire, and by Sweden. After Sweden lost to Russia in the Great Northern War in 1710, Russian rule was imposed on Estonia. However, the legal system, the Lutheran church, the local and town governments, and education remained mostly German-influenced until the late 19th century and partially until 1918.

The Estonian people didn’t stop dreaming of establishing a state free from foreign domination. The estophile enlightenment period from 1750–1840, when Baltic German scholars began documenting and promoting Estonian culture and language, led to the Estonian national awakening in the middle of the 19th century when Estonian arts, literature and a sense of identity started to flourish.

The 1917 Russian revolution and the generally unstable situation in Russia created the opportunity for Estonia to gain its independence. The impetus for independence was provided by the National Front, Estonia’s main ideological movement, which based its ideas on US president Woodrow Wilson’s principle of self-determination.

On 8 April 1917, 40,000 Estonians held a demonstration in St Petersburg in support of Estonian self-government. The peaceful demonstration achieved its goal when, on 12 April, the Russian Provisional Government signed the Law on Estonian Autonomy, which united the Livonian counties of Tartu, Võru, Viljandi, Pärnu and Saaremaa with Estonia. For the first time, an Estonian, Jaan Poska, was appointed as a provincial commissioner of Estonia.

A six-member Provisional National Council, the Maapäev, was formed. The Maapäev appointed a national executive that began to organise and modernise local government and educational institutions. Prior to its forceful dissolution by Bolshevik authorities and the impending invasion of Estonia by the German forces (as the First World War was still in full force), the Maapäev took a decisive step toward sovereignty by declaring itself the supreme authority in Estonia on 15 November 1917.

Independence proclaimed

In February 1918, after the collapse of the peace talks between Soviet Russia and the German Empire, mainland Estonia was occupied by the Germans. The Bolshevik forces retreated to Russia. Between the Russian Red Army’s retreat and the arrival of advancing German troops, the Salvation Committee of the Estonian National Council issued the Estonian Declaration of Independence on 23 February 1918.

The manifesto of Estonian independence was first read to the people from the balcony of Endla Theatre in Pärnu at eight o’clock in the evening.

On 24 February 1918, Estonia was publicly proclaimed as an independent and democratic republic.

This was not yet a happy ending, however. On 25 February, the German troops entered Tallinn. The German authorities recognised neither the provisional government nor its claim for Estonia’s independence, counting them as a self-styled group usurping the sovereign rights of the German-Baltic nobility.

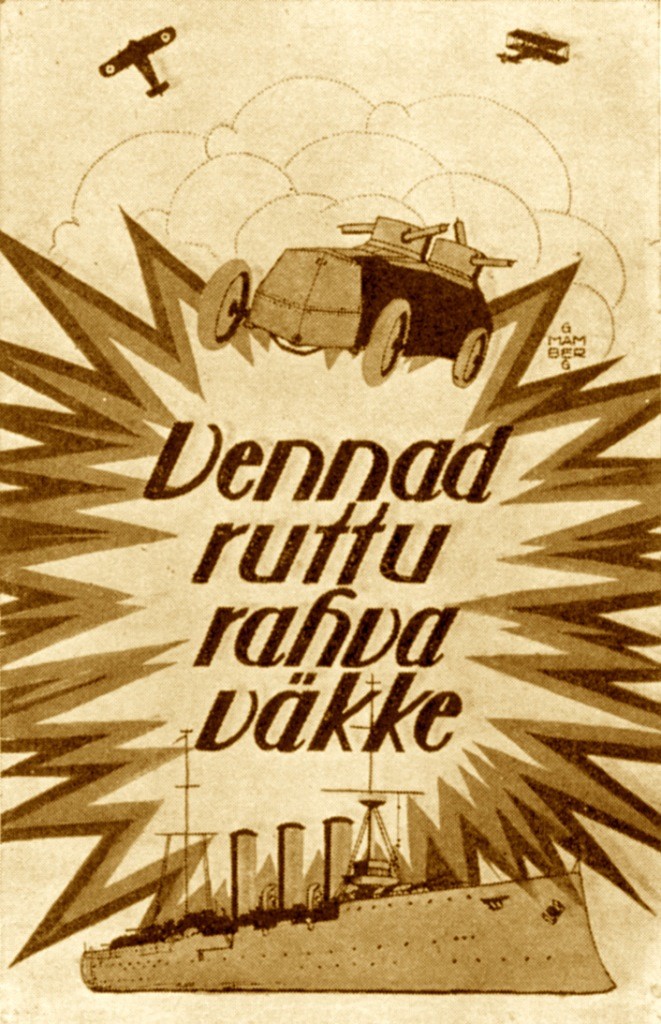

But with the First World War coming to its crushing end and forcing Imperial Germany to capitulate in November 1918, Germany formally handed over the political power of Estonia to the Estonian Provisional Government. The provisional government immediately called for voluntary mobilisation and began to organise the Estonian Army, which initially consisted of one division.

Russia attacks again

On 28 November 1918, the communist Red Army resumed its attack on Estonia when it took the offensive against the units of the Estonian Defence League (consisting partly of secondary school students), deployed in the defence of the border town of Narva. This marked the beginning of the Estonian War of Independence.

The Red Army attack came in an extremely difficult time. The Estonian administration and defence forces had very little experience. The army lacked sufficient weapons and equipment. Food and money were scarce; the towns were in danger of starvation.

Although the majority of the population did not support Soviet Russia, their faith in the survival of national statehood was not high. People did not believe that Estonia would be able to resist the attacks of the Red Army.

The people’s fear was not unfounded. The Red Army captured Narva and opened a second front south of Lake Peipus. But the Estonian government nevertheless decided to oppose the Russian aggression.

Estonia fights back

The Estonian military forces at the time consisted of 2,000 men with light weapons and about 14,500 poorly armed men in the Estonian Defence League. By the end of December, however, the young republic managed to reorganise its armed forces and recruit an additional 11,000 volunteers.

Estonia’s Baltic German minority, fearful of the communist Red Army, also came to Estonia’s rescue, by providing a sizable troop of volunteer militia.

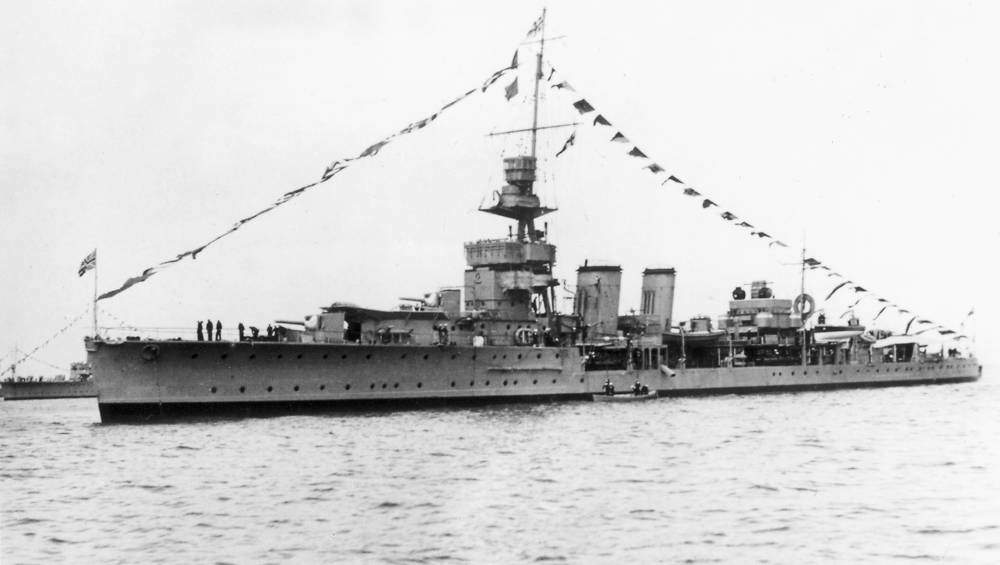

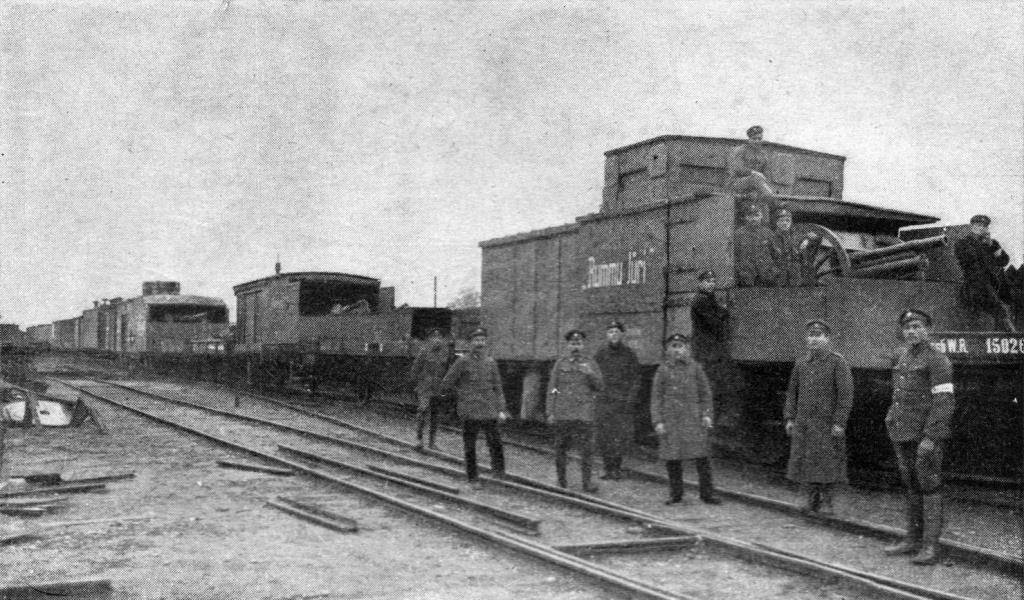

The country also managed to build three armoured trains and called for foreign assistance. In this hour of need, Estonia’s call for help was heeded. When the Soviet army had advanced to 34 kilometres (21 miles) outside of the Estonian capital in December 1918, a British Royal Navy squadron arrived in Tallinn, bringing guns, food and fuel.

The squadron also captured two Russian destroyers, Spartak and Avtroil, and turned these over to Estonia, which renamed them Vambola and Lennuk. The United Kingdom remained Estonia’s main supplier of arms and equipment during the war.

Furthermore, in January 1919, Finnish volunteer units, consisting of about 3,500 men, arrived in Estonia. Danish and Swedish volunteers also participated on the Estonian side.

The strengthened Estonian Army, now totalling 13,000 men, with 5,700 on the front facing 8,000 Soviet soldiers, stopped the advance of the 7th Red Army in early January 1919 and went on counter-offensive.

When the country celebrated its second Independence Day in 24 February 1919, the Estonian forces consisted of 19,000 men and Estonia had become the first country to repel the westward offensive of the Soviet Union.

Forcing the enemy out of the country increased faith in the authority of the young republic and enabled another mobilisation that was crucial in continuing the fight against a much bigger Red Army – at one point during the war, it had committed about 80,000 soldiers against Estonia.

By May 1919, the Estonian troops already contained about 75,000 men. The Estonian government and the army command were feeling so confident that they set a goal to push the front as far from Estonia’s borders as possible.

In May, the Estonian troops started an offensive towards Petrograd (St Petersburg) and conquered a large territory east of Lake Peipus. Later in the year, however, the troops retreated in order to protect Estonia’s borders.

Independence ensured

The War of Independence continued with heavy battles throughout 1919, with the Soviet forces repeatedly attempting to regain their lost ground. By the end of the year, the number of Estonian troops had increased to 90,000.

With Estonia’s strong resolve to defend its independence proven on one hand and the still relatively fragile Soviet Russian government attempting to ensure its Bolshevik revolution within the Russian borders on the other, Russia officially offered a peace agreement to Estonia.

Estonia emerged victorious, secured its borders and signed the Tartu Peace Treaty with Soviet Russia on 2 February 1920.

The country’s losses in the War of Independence were relatively small – about 2,300 killed and 14,000 wounded. Their sacrifice ensured that Estonia could enjoy freedom until 1940 and then again from 1991 onward.

Estonia in interwar period

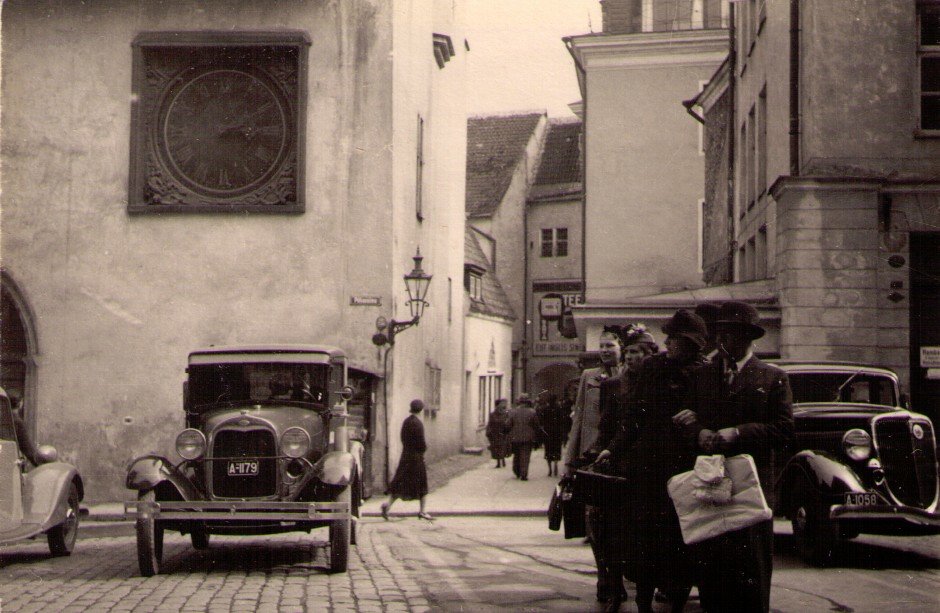

After becoming an independent nation in 1918 and signing the Tartu Peace Treaty with Russia in 1920, Estonia’s first constitution was promulgated, establishing a parliamentary system. In 1921, the country became a member of the League of Nations.

With a political system in place, the new Estonian government immediately began the job of rebuilding. As one of its first major acts, the government carried out an extensive land reform, giving tracts to small farmers and veterans of the War of Independence. The large estates of the Baltic German nobility were expropriated, breaking its centuries-old power as a class.

At first, agriculture dominated the country’s economy. Thanks to the land reform, the number of small farms doubled to more than 125,000. Although many homesteads were small, the expansion of landownership helped stimulate new production after the war.

The land reform, however, did not solve all of Estonia’s early problems. The Estonian agriculture and industry (mostly textiles and machine manufacturing) had depended heavily on the Russian market. Independence and the Soviet communism closed that outlet by 1924, and the economy had to reorient itself quickly toward the West, to which the country also owed significant war debts.

The economy began to grow again by the late 1920s, but suffered another setback during the Great Depression, which hit Estonia during 1931-34. By the late 1930s, however, the industrial sector was expanding anew, at an average annual rate of 14 per cent. Industry employed some 38,000 workers by 1938.

Independent Estonia’s early political system

Independent Estonia’s early political system was characterised by instability and frequent government turnovers. The political parties were fragmented and were about evenly divided between the left and the right wing.

The first Estonian constitution required parliamentary approval of all major acts taken by the prime minister and his government. The Riigikogu (the State Assembly, the Estonian parliament) could dismiss the government at any time, without incurring sanctions. Consequently, from 1918 to 1933, a total of twenty-three governments held office (in comparison, in 27 years after restoring its independence in 1991, just 16 governments have held office).

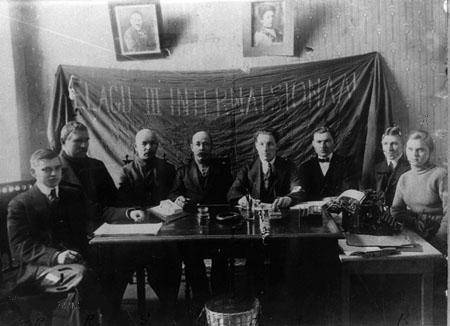

The country’s first big political challenge came in 1924 during an attempted communist takeover. In the depths of a nationwide economic crisis, the leaders of the Estonian Communist Party, in close contact with the Communist International leaders from Moscow, believed the time was ripe for a workers’ revolution to mirror that of the Soviet Union. On the morning of 1 December 1924, some 300 party activists moved to take over key government outposts in Tallinn, while expecting workers in the capital to rise up behind them. The effort soon failed, however, and the government quickly regained control.

In the aftermath, the Estonian political unity got a strong boost, while the communists lost all credibility. The relations with the Soviet Union, which had helped instigate the coup, deteriorated sharply.

By the early 1930s, Estonia’s political system, still governed by the imbalanced constitution, again began to show signs of instability. As in many other European countries at the time, pressure was mounting for a stronger system of government. Several constitutional changes were proposed, the most radical being put forth by the protofascist League of Independence War Veterans.

In a 1933 referendum, the league spearheaded replacement of the parliamentary system with a presidential form of government and laid the groundwork for an April 1934 presidential election, which it expected to win. Alarmed by the prospect of a league victory and possible fascist rule, the caretaker prime minister, Konstantin Päts, organised a pre-emptive coup d’état on 12 March 1934. In concert with the army, Päts began a rule by decree that endured virtually without interruption until 1940. He suspended the parliament and all political parties, and he disbanded the League of Independence War Veterans, arresting several hundred of its leaders.

The subsequent “Era of Silence” was initially supported by most of Estonian political society. After the threat from the league was neutralised, however, calls for a return to parliamentary democracy resurfaced.

In 1936, Päts initiated a tentative liberalisation with the election of a constituent assembly and the adoption of a new constitution. During elections for a new parliament, however, political parties remained suspended, except for Päts’s own National Front, and civil liberties were only slowly restored. Päts was elected president by the new parliament in 1938.

Although the period of authoritarian rule that lasted from 1934 to 1940 was a low point of the Estonian democracy, in perspective, its severity clearly would be tempered by the long Soviet era soon to follow.

The clouds over Estonia and its independence began to gather in August 1939, when Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact (also known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact), dividing Eastern Europe into spheres of influence. Moving to capitalise on its side of the deal, the Soviet Union soon began to pressure Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania into signing the Pact of Defence and Mutual Assistance, which would allow Moscow to station 25,000 troops in Estonia.

President Päts, in weakening health and with little outside support, acceded to every Soviet demand. In June 1940, the Soviet forces completely occupied the country, alleging that Estonia had “violated” the terms of the mutual assistance treaty.

With rapid political manoeuvring, the regime of the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, then forced the installation of a pro-Soviet government and called for new parliamentary elections in July. The Estonian Communist Party, which had only recently re-emerged from underground with fewer than 150 members, organised the sole list of candidates permitted to run. Päts and other Estonian political leaders meanwhile were quietly deported to the Soviet Union or murdered.

With the country occupied and under total control, the communists’ “official” electoral victory on 17-18 June with 92.8 per cent of the vote was merely window dressing. On 21 July, the new parliament declared Estonia a Soviet republic and “requested” admission into the Soviet Union.

In Moscow, the Supreme Soviet granted the request on 6 August 1940. The independent Estonia was finished. After a brief German occupation from 1941-1944 and the failed attempts to restore an independent Estonia, the Soviet Union occupied the country again; the occupation lasted until 1991.

The crisis in the Soviet Union opens a window of opportunity for Estonia

By the mid-1980s, the Soviet Union’s economy was in a critical situation, largely caused by a lack of technological development compared with the West, the inefficient socialist planned economy based on extensive production, and the preferred development of military industries. In the arms race with the main enemy, the United States, the Soviet Union turned out to be the loser, having exhausted its potential.

The Soviet export of oil and gas suffered seriously after fuel prices fell on the world market. At the same time, the Soviet Union increasingly depended on imported grain, which was unable to meet the demands of the domestic market. The increasing lack of food products and basic necessities (footwear, clothes etc.), plus escalating prices, caused bitter resentment among the population.

The Soviet foreign policy had reached a dead end as well, as it had been expansionist for decades, trying to extend Soviet power throughout the world. The war against Afghanistan started in 1979 and proved much more complicated than initially estimated. This brought about foreign policy complications and further strained the country’s economy.

The Soviet leadership did not publicly acknowledge the crisis. Therefore, many people, including most Estonians, were initially cautious of Mikhail Gorbachev, the new leader of the Soviet Union, who started his innovative policies in 1985. The keywords glasnost and perestroika (openness and reconstruction) seemed like empty slogans, and it was not clear what kind of reforms and changes the new Soviet leader was actually pursuing.

The first signs of radical changes in society emerged in Estonia in spring 1987, when the Soviet plans to establish phosphorite mines in northern Estonia were revealed. This unleashed an extensive protest campaign, the “phosphorite war”. This also marked the kick-off of the process of regaining Estonian independence, as the environmental issues were soon supplemented by political topics.

In August 1987, the Estonian Group on Publication of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was founded (the Estonian abbreviation: MRP–AEG). The group organised a mass meeting in Hirvepark in Tallinn the same month, where people demanded that the secret protocols of the 1939 pact be made public. The meeting was not forcefully disbanded, as would have happened before, which showed that civil rights had expanded and the regime had softened – the authorities even granted permission to hold the demonstration.

The Estonian society awakens

The Estonian society became politically active in 1988. A joint plenum of the creative unions (writers, artists, architects and theatre and film people), which focused on Estonian national culture and the threat of intensifying Russification, expressed dissatisfaction with the activity of the Soviet Estonian leadership.

In mid-April, the Estonian Popular Front in Support of Perestroika was founded. This moderate, but clearly innovative movement wanted to make the Soviet Union more democratic and demanded political and economic autonomy for Estonia within the Soviet Union. The moderate aims of the Popular Front were enthusiastically supported by the Estonian population and it quickly became a powerful mass organisation.

The early summer of the same year witnessed a series of concerts and joint singing, soon to turn into a large-scale popular movement, and later called the Singing Revolution.

Besides the moderate course, a more radical national movement emerged in 1988, which was clearly directed at restoring Estonia’s independence. The Estonian Heritage Society, established at the end of 1987, used totally un-Soviet rhetoric. In August 1988, the first Estonian political party was founded: the Estonian National Independence Party (the Estonian abbreviation ERSP). Its core was made up of the MRP–AEG members.

In the summer, the Supreme Soviet of Estonia adopted the blue-black-white flag of the Republic of Estonia once again as the Estonian national flag.

On 16 November 1988, the Estonian Supreme Soviet passed the Declaration of Sovereignty, which confirmed the supremacy of laws passed by the Soviet in the Estonian SSR. The document also declared that the basis of the relations between the central authorities of the Soviet Union and a Union republic must be an agreement that would establish the rights and duties of both sides, achieved by negotiations. Moscow declared the declaration null and void, but was unable to halt the process of restoring independence.

A special mass undertaking by independence-seeking forces in the Baltic countries was the Baltic Chain, which attracted keen interest in the foreign press. On 23 August 1989, on the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, about two million people formed a living chain from Tallinn via Riga to Vilnius, thus eloquently demonstrating their wish for independence.

Estonia regains its independence

In the spring of 1990, the Estonian SSR Supreme Soviet declared the authority of the Soviet Union in Estonia illegal. A transition period was announced, which, in cooperation with the Estonian Congress, would lead to the restoration of the Republic of Estonia. In May, the name Estonian SSR was abolished and replaced by the Republic of Estonia.

However, independence had not yet been achieved. The Soviet Union still considered Estonia and the other Baltic republics to be Union republics subordinated to Moscow, and was prepared to use extreme force to maintain its power, as seen in the violent events in January 1991 in Vilnius and Riga.

In both capitals, the Soviet special troops tried to seize the media centres controlled by national forces, and dozens of people were killed. Estonia was spared violence, apart from the attack at Ikla border control point by special militia units of the Soviet Union in June 1991.

Finally, Estonia took the advantage of the attempted coup d’état (the ‘August putsch’) in Moscow in August 1991. On 20 August 1991, the Estonian Supreme Soviet, in agreement with the Estonian Committee (the executive organ of the Estonian Congress) proclaimed Estonian independence, thus restoring the Republic of Estonia, which had been legally established in 1918 and illegally occupied in 1940 by the Soviet Union.

This decision was quickly followed by the restoration of diplomatic relations and recognition of the Republic of Estonia by many countries, including Russia and the Soviet Union (which ceased to exist four months later).

The Republic of Estonia was restored on the basis of legal continuity – it was first established on 24 February 1918 – and that is why the country is celebrating its independence on that date.

Since restoring its independence, Estonia has introduced many reforms, joined the EU and NATO, and is one of a handful of countries closest to becoming a digital society. In many aspects, the country is punching above its weight internationally. It has proven in the last 32 years that it can do very well as an independent country.

* This article was originally published on 24 February 2015.

Happy Independence Day! Stay alert!

Well put together history lesson. Tänan! Long live Estonia!

Thank you for a very much needed over-view of the history of our tiny nation. So Proud to be Estonian.

I’m so impressed. I had overlooked this rich history.Thanks for sharing.

Happy birthday :* my dear and a big sweet estonia , my sisters , brothers and childrens .)

Palju õnne, julgustav ajalugu

Happy Independence day from Finland! Total bros!

Wish you a very Happy Independent Day Estonia

The Estonian history is partly quite similar as Finland’s. Wehave our Independance Day on Dec.6th since 1917 thus it’ll be 100 years this year. Before the 1917 Russian revolution the country belonged to Sweden until 1809 and then to Russia. Being a country near the Big Bear bot Estonia and Finland have had their bad times with the neighbour and also good times together against the enemy. Hopefully we’ll have peace all over the world – some day. The Finnish and Estonian languages are quite similar though they understand us better than we do -they used to watch Finnish TV before 1991 !

Very concise and well written. Lets hope Estonia has a bright future.

You have forgot the war against Baltic-German Landeswehr:

“The war against the Baltische Landeswehr broke out on the southern front in Latvia on 5 June 1919. The Latvian democrats led by Kārlis Ulmanis had declared independence like in Estonia, but were soon pushed back to Liepāja by Soviet forces, where the German VI Reserve Corps finally stopped their advance. This German force, led by general Rüdiger von der Goltz, consisted of the Baltische Landeswehr formed from Baltic Germans, the Guards Reserve Division of former Imperial German Army soldiers who had stayed in Latvia, and the Freikorps Iron Division of volunteers motivated by prospects of acquiring properties in the Baltics.[26] This was possible because the terms of their armistice with the Western Allies obliged the Germans to maintain their armies in the East to counter the Bolshevist threat. The VI Reserve Corps also included the 1st Independent Latvian Battalion led by Oskars Kalpaks, which consisted of ethnic Latvians loyal to the Provisional Government of Latvia.[1]

The Germans disrupted the organization of Latvian national forces, and on 16 April 1919 the Provisional Government was toppled and replaced with the pro-German puppet Provisional Government of Latvia led by Andrievs Niedra.[27][28] Ulmanis took refuge aboard the steamship “Saratow” under Entente protection. The VI Reserve Corps pushed the Soviets back, capturing Riga on 23 May, continued to advance northwards, and demanded that the Estonian Army ended its occupation of parts of northern Latvia. The real intent of the VI Reserve Corps was to annex Estonia into a German-dominated puppet state.

On 3 June, Estonian General Laidoner issued an ultimatum demanding that German forces must pull back southwards, leaving the broad gauge railway between Ieriķi and Gulbene under Estonian control. When Estonian armoured trains moved out on 5 June to check compliance with this demand, the Baltische Landeswehr attacked them, unsuccessfully.[29] The following day, the Baltische Landeswehr captured Cēsis. On 8 June, an Estonian counterattack was repelled. First clashes demonstrated that the VI Reserve Corps was stronger and better equipped than the Soviets. On 10 June, with Entente mediation, a ceasefire was made. Despite the Entente demand for the German force to pull behind the line demanded by the Estonians, von der Goltz refused and demanded Estonian withdrawal from Latvia, threatening to continue fighting. On 19 June, fighting resumed with an assault of the Iron Division on positions of the Estonian 3rd Division near Limbaži and Straupe, starting the Battle of Cēsis. At that time, the 3rd Estonian Division, including the 2nd Latvian Cēsis regiment under Colonel Krišjānis Berķis, had 5990 infantry and 125 cavalry. Intensive German attacks on Estonian positions continued up to 22 June, without achieving a breakthrough. On 23 June, the Estonian 3rd Division counterattacked, recapturing Cēsis. The anniversary of the Battle of Cēsis (Võnnu lahing in Estonian) is celebrated in Estonia as the Victory Day.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Estonian_War_of_Independence

You are missing the Landeswehr story – when Estonia battled Baltic German forces.