Estonian diplomats in exile worked tirelessly to ensure that Estonia was not forgotten and that the Soviet occupation was reported accurately.

The current London Diplomatic List weighs in at a hefty 142 pages. Listed within are the names and positions of every diplomatically accredited member of staff of all foreign embassies, high commissions and international organisations (with some variation in diplomatic status) to be found in the capital.

To the outside observer, this might seem like an uninteresting and somewhat bland directory of names. But to those of London’s large diplomatic community it is one of the most important documents in existence – it enshrines their status in law under the Diplomatic Privileges Act 1964 which gives them, among other things, immunity from criminal prosecution.

During the Cold War, the list ended not as it does now, with a run-down of international NGOs, but with a small section entitled: “List of persons not included in the foregoing list but still accepted by Her Majesty’s Government as personally enjoying certain diplomatic courtesies”.

Essentially this category was devised for the representatives of formerly independent countries which had been annexed by the Soviet Union. Despite recognising the de facto position of these countries as being occupied, they rejected the legal basis upon which the annexation was founded and continued to recognise their independent diplomatic representatives in London.

Estonian envoys in London

Appointed in 1934, the Estonian envoy in London was August Torma, a former military officer and career diplomat, formerly envoy to Italy, Switzerland and the League of Nations.

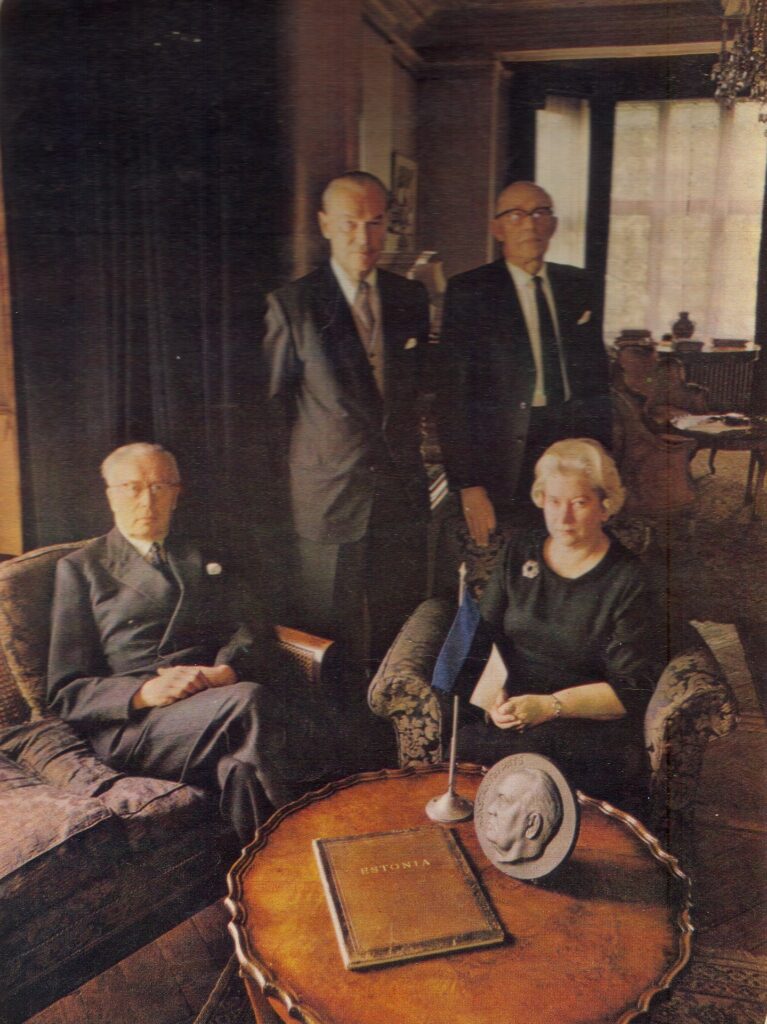

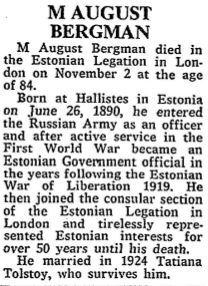

Born in 1895 near Pärnu, he served in the Russian Imperial Army and the British Expeditionary Force before becoming a military attaché and diplomat. Serving alongside him were (his eventual successors) counsellors Ernst Sarepera and August Bergman.

After the end of the Second World War, they found themselves in a bizarre (but not unheard of) situation in that they had no governments to represent. Unlike previous representatives of conquered or annexed countries (such as France in WWII), there was no “government in exile” functioning elsewhere which still needed representation.

Granted, there was a body in Sweden claiming to be the legitimate government in exile, but it had little diplomatic recognition outside the country. As such, Torma and his colleagues found himself stuck in a sort of diplomatic limbo, with no orders to receive and nobody to whom he could give orders.

As the Cold War grew chillier, the status of these stateless ambassadors started to cause headaches for the British Foreign Office, particularly when it came to dealings with the Soviet Union, who regarded the Baltic legations with absolute suspicion.

Britain’s policy towards the Baltic representatives was a sort of “halfway house”: while it did not recognise the Soviet annexation de jure, it did recognise it de facto (in a stark contrast to the United States, which refused to accept both the de jure and de facto position of the occupation). Torma’s relationship with the British authorities hence had its ups and downs – he was sometimes understandably frustrated by an apparent desire on the part of the British to avoid upsetting the Soviets.

Ensuring that Estonia was not forgotten

Life for Torma and his compatriots was difficult. Initially they had relied on a Foreign Office grant, yet often day-to-day expenditure was met through pawning of the personal possessions of staff members.

Soviet attempts to have the legation disbanded were numerous but all failed, generally because of Torma’s persistence and determination. It was due to his foresight and quick thinking that Estonia’s gold reserves were transferred to London before they could be acquired by the Soviet Union immediately after Estonia was annexed.

The duties of the legation consisted mainly of administrative tasks such as issuing birth certificates and translating them into English (so as to be used to accompany a pension claim) and registering deaths. Interestingly, they also issued passports, mainly to Estonians who wished to visit the US, one of the few places where an Estonian passport was still valid. They also worked tirelessly to ensure that Estonia was not forgotten and that the Soviet occupation was reported accurately, often by writing letters to newspapers and through attendance at society functions.

Yet despite the obvious risks that being an exiled minister in the height of the Cold War entailed, it was death by natural causes that was to prove most troublesome. In 1970, Torma died and was followed shortly afterwards by his legal successors, Sarepera and Bergman.

His obituary in The Times noted that “he enjoyed great respect for his unequalled knowledge of the Baltic and indeed the Soviet scene” and made reference to his vice presidency of the British and Foreign Bible Society.

Due to the legation’s lack of de jure recognition, a successor could not be appointed – the Foreign Office insisted that only those who had been accredited under the last legitimate government were eligible for diplomatic status. The day-to-day work of the legation was then undertaken by Anna Wagerstrom-Taru, a staff member albeit without diplomatic accreditation.

Reluctant decision to sell the old embassy building

For most of the rest of the Cold War, the 40-room-mansion that was the Estonian legation building (it was never referred to as an embassy, even during independence) in 167 Queens Gate remained more or less as Torma and his colleagues had left it, with old furniture covered by cloths and dusty rooms that lay empty.

The Soviets, in the shape of Ambassador Leonid Zamyatin, made a final attempt during the 1980’s to try and take over the building through legal means, but the combined resistance of Wagerstrom-Taru, despite ill-health, and the Estonian Consul General in the New York won through and the attempt was thwarted. New York continued to provide for the maintenance of the building in London until 1989, when the financial pressure became too great and they made the reluctant decision to sell.

However, none of the £2,500,000 raised through the sale was available until after independence – the High Court ruled, after an application by the Foreign Office, that as the last owner of the building, the Estonian National Bank, had ceased to exist then the money was to remain with the British Treasury.

The spirit of these exiled diplomats lives on today in the Hyde Park Gate building which houses the present embassy.

Her Excellency Ms Aino Lepik von Wirén, Estonian Ambassador to the UK, commented: “It is hard to overestimate Torma and his colleagues’ contribution in defending Estonia’s interests at the political as well as the interests of Estonian citizens at consular level. We can be thankful to them and to all other Estonian diplomats who continued their work abroad during the Soviet occupation. Likewise, we can be thankful to those foreign governments who made it possible for our diplomats to continue working.”

For Torma, Sarepera and Bergman independence came far too late, but Wagerstrom-Taru was still alive when a new ambassador to the UK was appointed in 1991 (she died in 1995). Their bravery and dedication bore testimony to a proud spirit of Estonian independence.

Mrs Taru was a clam and dignified person who kept the flame of Estonian freedom alive in the most difficult years. I am proud to have known her.

I knocked on the door in 1982 on a visit from Australia and the acting ambassador gave us a tour of the elegant and immensly sad building in Queens Gate.

So glad to learn that she lived to see 1991 and independence.

I stayed with Mr. Torma for several days in the fall of 1970, on my way to spend a year at the Department of Theoretical Physics in Oxford from the University of Toronto, Canada, where I had just obtained my PhD in physics. Mr. Torma was a very gracious host, but he was a fast eater and I was greatly embarrassed when he finished eating his meal and I had barely got started.

Jaan Noolandi

The top picture is of the right street but of the wrong building(s). 167 Queen’s Gate is a few blocks to the right.