Just days before the European Parliament election in May, the Estonian society was rocked by allegations in The Guardian newspaper of the inherent security flaws in the well-established e-voting system. For all in the know, as well as probably a large majority of the country, the shock was not about these apparent “flaws”, but about being caught off-guard by a political attack in the international media. Almost a month after the election, no serious information that could put into question the security of e-voting has emerged.

A group of “independent experts” found “serious security problems” in the system after having allegedly created the same system in laboratory conditions which led them to discover serious technical and procedural issues.

The Estonian cyber security expert, Anto Veldre from CERT, very succinctly described (in Estonian) how criticisms of various IT projects tend to come in two categories: technical and PR (political). When a technical security flaw is found in a system by an external party, the responsible thing to do is to first inform the developer and only publicise the vulnerability once a patch is available.

This team asked Estonia to immediately discontinue the use of the e-voting system. Even after making such a preposterous claim to the government of a sovereign democratic country, the team would not give any details until after the election (they did publish the results on a website, but did not show any credible problems). Not only was this a very political move to make, it was bordering on irresponsible. If no concrete flaw is identified, it cannot be verified or fixed. But the political opponent has made their move successfully – uninformed journalists pick up the headlines and because the inner workings of the e-voting system are so complicated, no one bothers figuring out how much substance the initial claims had.

The group claims, for example, that because in one public picture the password to the public WiFi available at the election authority’s office is visible on the back wall (just like in any other office with a public WiFi), it demonstrates the lacklustre approach of the authorities. Frankly it is very hard to take anything seriously from the “expert” after a claim like that.

What makes the recent attack political rather than technical is firstly the deeply political nature of the process and secondly the implausibility of their claims. The political nature of the team and their claims was all too clear from the way the revelations were made. For example, one of the experts, Harri Hursti, has repeatedly participated in the Estonian Centre Party’s anti e-election propaganda events before. This attack started with a very doom-and-gloom press release where the experts claimed to possess “evidence” of security flaws in the e-voting system. This happened just a few weeks before the election. No verifiable evidence was given. The information published after the election will probably help the authorities to tighten procedures in some ways, but most definitely there was not anything there to question the security of the elections.

The sole aim of the entire exercise was to discredit the electoral system of Estonia, as well as to undermine the established democratic system.

There is an inherent beauty to the way secure systems are developed. In pursuit of pure perfection, all developers understand (hopefully quite early in their career) that it is not attainable. No system has ever been perfect, be it the Titanic or the Death Star. This inherent flaw is what makes the systems beautiful. As a result, safeguards are put in place. This includes audits, not only for the IT-system, but also for the procedures and the results. It includes constant monitoring of the system and improvements and patches throughout time. Most importantly, it includes an acceptance of imperfection. For example, the fact that voters’ computers might be infected with malware was acknowledged as a risk before the system was rolled out. Just like it is very hard to make sure that all voters only make informed decisions, the state cannot control that everyone practices good computer hygiene. But this is an accepted risk – that is where safeguards come in.

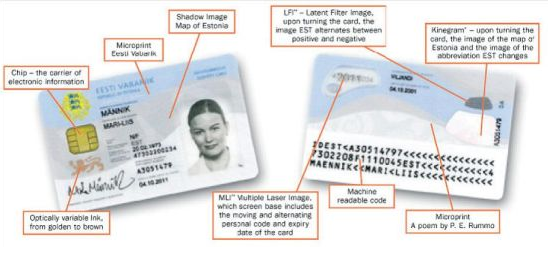

Just like no one can really know whether a voter is casting their vote the traditional way without any external duress or that the voting authority is not inundated with spies working for a foreign power, there are some risks connected to online voting. E-voting was created with an already conscious acceptance of flaws connected to voting – so it was intended to be much more secure than traditional ballots. Encrypted connections, fool proof authentication thanks to the national ID-card and the ability to change your vote as often as one would like up to the deadline have helped Estonia create an unparalleled system in the world that has worked without exploited vulnerabilities for six elections and will continue to do so for many elections to come.

I

Cover photo: Estonian ID-card, used for e-voting.

I think the best way to solve this is to allow independent experts to examine the system (including source code).

here you go:

https://github.com/vvk-ehk/evalimine

Rather than trying to discredit the accredited election observers (many of them respected security experts) as politically motivated, it would have been better to explain what has been done to alleviate the security concerns. There were clearly technical and well founded, and you are not doing yourself (or the credibility of your e-voting system) a favour by simply dismissing them.

For factual information about the security flaws, I recommend the article in the Guardian:

http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/may/12/estonian-e-voting-security-warning-european-elections-research

Hope, you will find some answers here: https://www.ria.ee/e-voting-is-too-secure/

I believe the question should be not whether a voting system is perfect, but whether it’s more perfect than any other voting system. All have flaws, but I suspect the Estonian e-voting system has far fewer flaws than most.

This article seems slanted the other direction. They make fun of how critics didn’t like that the wifi network password was posted on the wall — but why do they think that’s OK? Sure, for your home network it’s fine, but based on the report (I read it), there were lots of basic IT procedural lapses (loading the software from someone’s personal USB stick, etc) that really shouldn’t be there if we’re talking something important like voting. Why are such lapses OK?