An exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London highlights the historical products once manufactured by Estonian plywood producers.

A small but extraordinary exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum gives us a concise social history of one of the most fascinating materials – plywood. It sheds light over 120 objects and focuses on the development of design and industry over the past 150 years. Cars, dinghies, aeroplanes; chairs, tables, and architectural solutions – it all displays the ways plywood has shaped the modern world.

Hold on; is plywood – the material of the modern world – actually old or new? Due to reinvention and hand-making turned into digital manufacturing, plywood seems to be a perennially modern material. The technique of layering cross-grained veneers to make a material stronger than just solid wood was known a long time ago – as early as 2600 BC in ancient Egypt. Archaeologists have discovered it was trendy to use laminated timber to make a range of things from jewellery boxes to coffins for pharaohs.

Noticing Luterma hatboxes, bags and suitcases in the limelight of this exhibition is as heart-warming for me as, for example, seeing photos of my Estonian ancestors using the same kind of items while travelling in the then world. The whole collection displayed – plus many more – were made in Estonia, manufactured by Luterma (previously A. M. Luther), and distributed by Venesta.

Made in Estonia

Luterma was an important 20th century Estonian plywood manufacturer, with a large British distributor called Venesta. They sold moulded products like these in great quantities. The hatboxes, handbags and suitcases were marketed as lightweight and strong, and came in a range of sizes, telling the world about a move towards smaller luggage in the1920s and ‘30s, linked to new kinds of travel in aeroplanes and cars.

Plywood was widely experimented in connection with vehicle construction between the First and the Second World War. From 1928, the German manufacturer, DKW, used moulded plywood for the bodies of their affordable family cars. Combatting prejudice that plywood was less reliable than metal, the German producers emphasised its unique properties – strong and stress-bearing, easy to repair and quieter on the road due to better suspension.

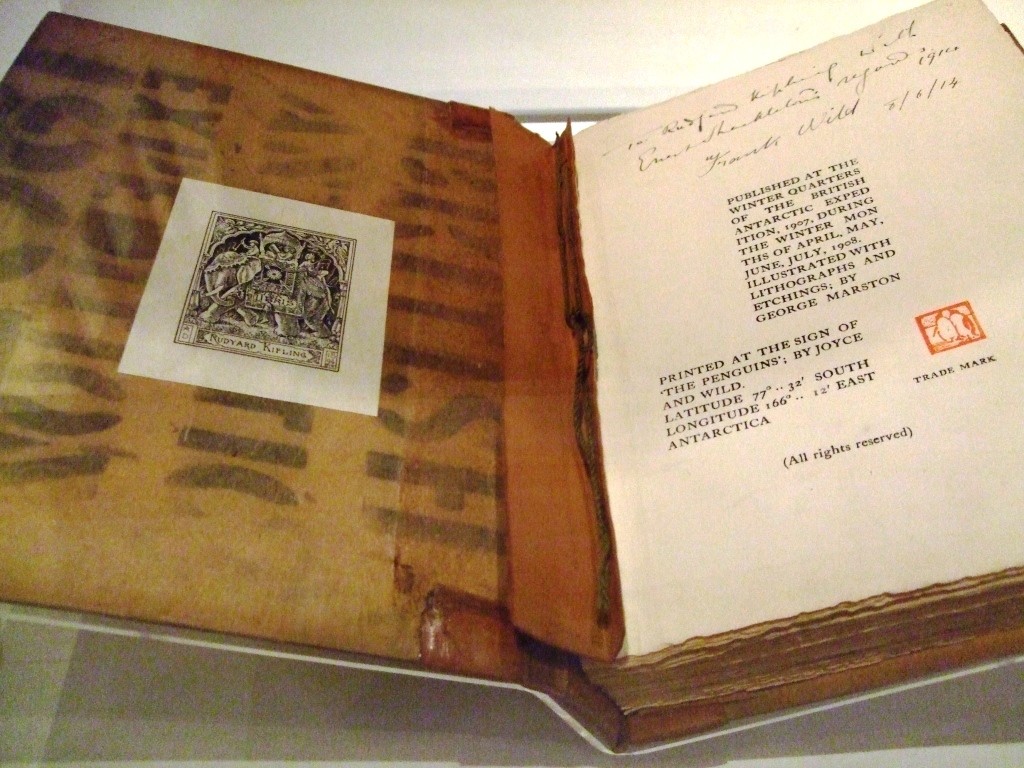

With specimens of boats, planes and chairs dangling from the ceiling, the plywood show brings to one’s mind a knowingly arranged all-in-one shop, displaying old trends and highlighting the humble origins of what we might consider new. Examples range from plywood packing cases taken to the Antarctic by Ernest Shackleton’s expedition, where some of them were broken down and transformed into furniture, to the most stylish chairs from the middle of the 20th century.

Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition to the Antarctic (1907-09) required about 2,500 plywood packing cases. Among other things, Shackleton and his crew took a printing press on their expedition – to guard them from the danger of lack of occupation during the polar night. Some of the plywood cases that carried their provisions were cleaned, planed and polished to be used as bindings for the books. Aurora Australis (1908), written, illustrated and published by the British Antarctic Expedition crew members was printed with binding of Venesta three-ply birch plywood, leather and green silk cord, and presented to Rudyard Kipling by Ernest Shackleton in 1914.

Versatile use

One of the most prescient was a plan for a pneumatic railway in a big plywood tube, designed to hang off the side of buildings, the drawings of which were published in 1867. It makes you instantly think about Elon Musk’s plan for Hyperloop.

Although plywood was widely known and also used from the 1880s, prejudice against it as cheap or poor quality meant it was often used structurally or hidden under other materials. Today, plywood is common in the construction industry, yet it was not until 1930s that architects and builders first began to experiment with it as a building material. Plywood was of interest to modernist designers because it was seen to be industrial and symbolised the new machine age. Certainly, a big part of the appeal was low cost, uniformity and the fact that it was factory-produced in standard sizes.

The invention of synthetic glues in the 1930s revolutionised the use of plywood; it meant that manufacturers could also produce new types of waterproof plywood, ideal for exterior use. The other side of the coin was that the rise of synthetic adhesives and the lack of standards for adhesives helped create the so called petrochemical homes. Nowadays, there are strict standards for adhesives, but taken into account that a vast bulk of plywood is manufactured in the countries where the illegally logged wood is also on the rise, the production of plywood cannot be brought under strict control.

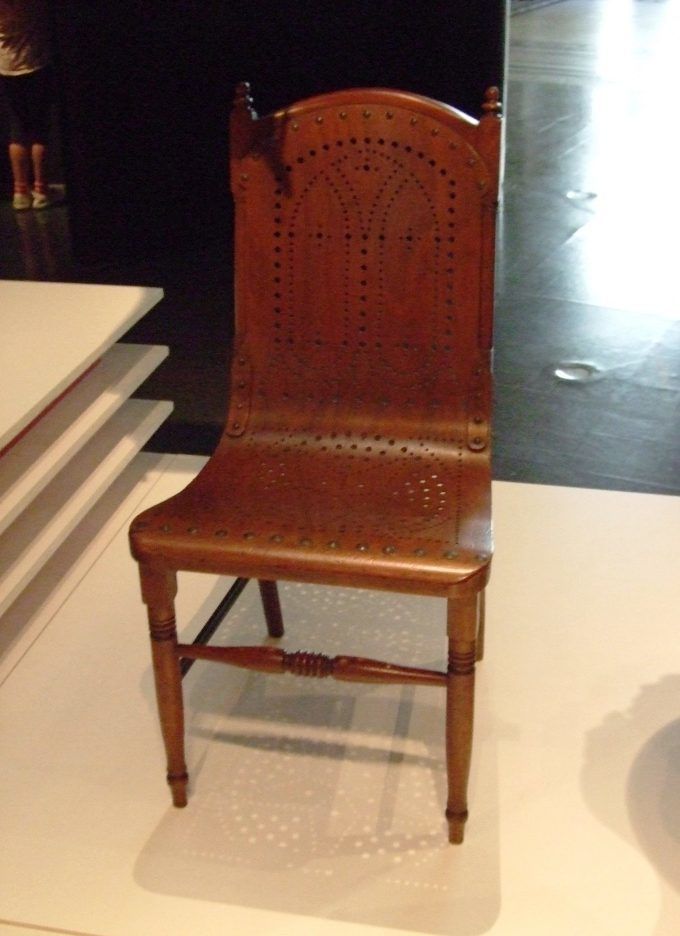

During the 1870s, the New York firm, Gardner & Company, patented a chair with a single piece seat and back of moulded plywood. The seat and back ingeniously formed a self-supporting structure that could be attached to any minimal frame – this made the chair lighter and cheaper to produce.

During the 1870s, the New York firm, Gardner & Company, patented a chair with a single piece seat and back of moulded plywood. The seat and back ingeniously formed a self-supporting structure that could be attached to any minimal frame – this made the chair lighter and cheaper to produce.

No wonder it was a commercial success imitated across Europe, appreciated equally in houses around the Baltic Sea and in the Alpine homes. A.M. Luther manufactured the chairs in Estonia as a part of his fashionable American Furniture range.

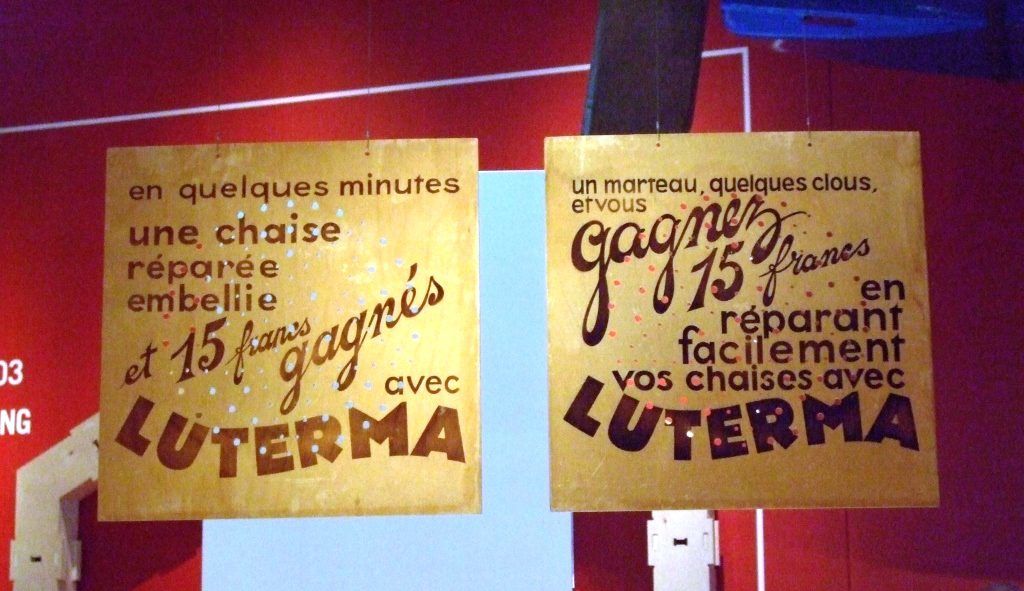

What if your modern chair gets broken? No need to worry! In a few minutes, a chair repaired, embellished and 15 francs saved, with Luterma. A hammer, a few nails, and you save 15 francs by easily repairing your chairs with Luterma. These are the messages conveyed by advertisements – perforated plywood posters – used in French shop windows and elsewhere during the 1920s to promote plywood seats that were easily attachable to existing frames.

Luterma copied Gardner & Company by using perforations to make their brand instantly recognisable. The two jazzy ads displayed at the London show come from the private collection that belongs to Dr Jüri Kermik, a widely recognised authority in the field. His The Luther Factory, Plywood and Furniture 1877-1940, published by the Museum of Estonian Architecture in 2004 is a thorough survey of the period.

Fascinated by its thinness, flexibility and strength, furniture designers – who perceived that the time was right – started seriously experimenting with plywood to create attractively light and curved forms. In 1929, the Isokon company was founded in London by the entrepreneur, Jack Prichard, the architect, Wells Coates, and others.

Isokon produced thoroughly modern architecture and furnishings, most often in plywood. Interestingly, Prichard had previously worked for Venesta, the British distributor of the Estonian plywood company Luterma. The pride of the present display is their lightweight plywood stool (1.1 kg; 2.4 lbs) that was made by Luterma and sold in Britain by Isokon.

In the year 1932, the Finnish architect and designer, Alvar Aalto, designed his famous chair for the Paimio Tuberculosis Sanatorium in Finland. A year later the chairs were already manufactured for general sale, alongside his other furniture designs. Aalto’s furniture was exported in large quantities to the United Kingdom and the US. No doubt his innovative use of plywood had a significant impact on other designers.

In the year 1932, the Finnish architect and designer, Alvar Aalto, designed his famous chair for the Paimio Tuberculosis Sanatorium in Finland. A year later the chairs were already manufactured for general sale, alongside his other furniture designs. Aalto’s furniture was exported in large quantities to the United Kingdom and the US. No doubt his innovative use of plywood had a significant impact on other designers.

Short Chair, designed by Marcel Breuer, came into the limelight in 1936. Its thin and light seat was moulded as a single piece of plywood. The beauty of this piece of furniture lies in the impression of the seat floating on air, suspended in its frame. Plywood seats for Breuer’s Short Chairs were moulded in batches by the Estonian company Luterma; they were shipped to Britain and then attached to locally-made laminated wood frames.

Educating on design and technology

Plywood was also successfully used to produce door handles and doors. And then, in the 1930s, Plymax, a branded copper-faced plywood manufactured by Luterma for both industrial and architectural use, became fashionable. The Plymax door displayed at the exhibition was designed for the penthouse apartment of Lawn Road Flats, a modernist apartment block in Hampstead, London. The famous crime novelist, Agatha Christie, who used to live in one of the flats, probably derived some feel of avant-garde modernist design reflected in her many works also from the Isokon Building.

By using Plymax, the designers, Wells Coates and Jack Pritchard, exploited a modern material with industrial associations while also creating a rich decorative surface. Nowadays, the most modern floor designers offer similar solutions based on computer designed processed wood, and once again, the question arises – old or new?

The exhibition displays an educating story of design and technology that has been shaped by taste and prejudices in different times.

I

Cover: Short Chair, designed by Marcel Breuer. Images by Ann Alari.