On the occasion of the day celebrating the restoration of independence, Estonian World has chosen 12 of Estonia’s most outstanding statespeople in recent times.*

In the evening of 20 August 1991, Estonian parliamentarians decided to take advantage of the chaos in Moscow – the conservative Soviet hardliners had gone on offensive against the reformist Mikhail Gorbachev and attempted a military coup – and declared the nation’s independence.

Luckily for Estonia, the attempted coup d’état in Moscow failed and the more liberal forces, led by the chairman of the Russian SFSR Supreme Soviet, Boris Yeltsin, prevailed – thus starting the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Estonia was free again. The first country to diplomatically recognise Estonia’s reclaimed independence was Iceland, on 22 August. The Soviet Union finally recognised the independence of Estonia on 6 September 1991.

A lot has happened since, both good and bad. All in all, Estonia has done well by most accounts, but not in everything.

The country stood out for brave economic reforms in the 1990s and has become one of the most advanced digital societies in the world today. Successive governments have followed strict budget discipline and Estonia is one of the few NATO members to fulfill an obligation to spend at least 2% of GDP on defence. The number of startups and innovative companies – many of them started by high-school students on these days – is really impressive. In PISA tests, Estonian 15-year-olds – if not necessarily the happiest of chaps – are the best in Europe and third on the global scale.

On the other side of the coin, however, a whopping 21.3% of the Estonian population lives in relative poverty and 3.9% in absolute poverty. The country has also lost many of its bright minds and skilled workforce to Scandinavian countries, Germany, the UK and other countries. Salaries are still very low while the cost of life is rocketing. The gender pay gap is the largest in the European Union and the country has had only moderate success at best integrating its large Russian minority. Estonia has currently also the highest prevalence of HIV/AIDS in Europe – and the issue is constantly brushed aside.

“Ninety percent of the politicians give the other ten percent a bad reputation,” Henry Kissinger, the legendary former US secretary of state, once said. It’s an impossible task to figure out how many politicians in Estonia have had a genuine mission to make life better for everyone – and how many have acted merely for personal gain. It is fair to say that in a democratic society like Estonia, we – citizens, voters, members of parliament, state officials – are all responsible for Estonia’s wins and failures.

On the occasion of the day celebrating the restoration of independence, Estonian World highlights 12 of the country’s most outstanding statespeople of the last 26 years. Most of them have had their failures, too – but this publication believes they deserve a credit for various reasons: either for their hard work and resolve to make Estonia a better place during toughest of times, their grand vision, or for inspiring the nation.

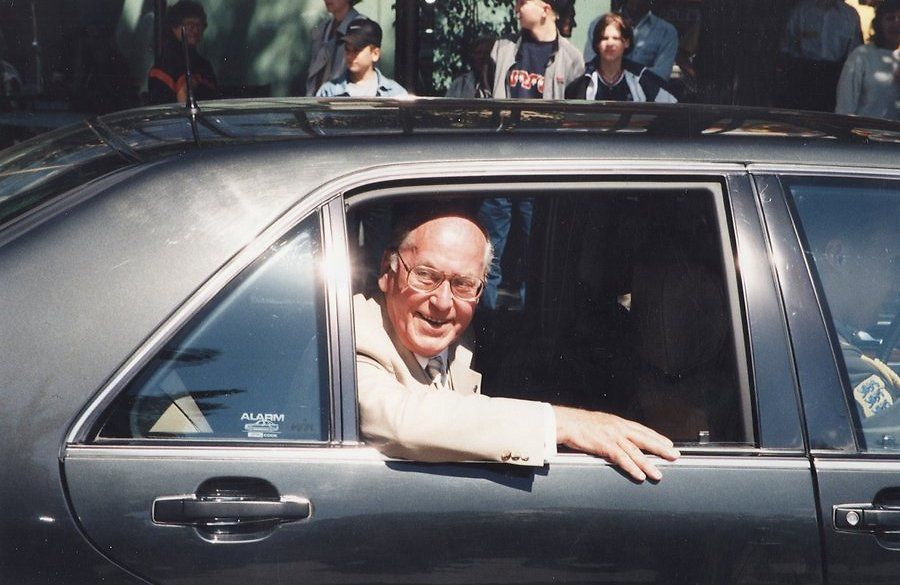

Lennart Meri

Estonia’s second president – and the first after the restoration of independence – is arguably one of the greatest – if not the greatest – of statespeople Estonia has seen in the last 30 years. Intellectual, yet approachable, Lennart Meri had this marvellous ability that most contemporary politicians lack – he could relate as easily with an average Joe as he could with the world leaders in Washington, Paris or Berlin.

He was truly cosmopolitan from the start – born to the family of an Estonian diplomat, Meri had left Estonia at an early age and studied abroad in nine different schools and in four different languages – but he never forgot his roots and had a great knowledge of the country’s history. In fact, as a writer and a documentary film director, he found a way to contribute to the preservation of the Estonian national identity even during the darkest times of the Soviet occupation.

His work and achievements prior to the restoration of independence are so extensive that they deserve a separate article – hence we focus on his tenure as president and borrow the characterisation from another heavyweight who, as a prime minister at the time, worked very closely with president Meri in 1992-1994, Mart Laar. We couldn’t put it any better.

Laar wrote these lines about Meri in 2013: “He was born in independent Estonia, lived there until its destruction and then moved with his nation to the Golgotha Mountain. He worked hard for the restoration of Estonia’s independence.

“Meri was the president of Estonia in the most difficult years of our restored independence. The banks collapsed, criminality was very high and people earned 60 euros per month. The situation looked quite hopeless. Meri, nevertheless, kept the nation together and calmed the tensions. He gave to the Estonian people a vision that united us – Europe. This was not an easy task. He was very outspoken and for his prime ministers and governments he was not an easy person to deal with. Occasionally, he clearly crossed the borders of the Estonian constitution. But his way of doing things worked. The people lived miserably, but they liked the direction in which Estonia was heading. Meri also liked the truth and was very frank.”

Mart Laar

Probably one of the most important – if not the most important – statesmen in the history of the post-occupation Republic of Estonia, Mart Laar was the first prime minister of the country after it had restored its independence. Having held the post twice (1992-1994 and 1999-2002), he’s widely credited for the important economic reforms that Estonia undertook to shake off the remnants of the Soviet occupation and set the path to again becoming a full member of the Western world.

His government, from 1992-1994, introduced the flat tax system in Estonia, privatised most national industries in transparent public tenders, abolished tariffs and subsidies, stabilised the economy, balanced the budget, and, probably most importantly, restored the strength of the national currency – the kroon – pegging it to the stable Deutsche Mark. His reforms and politics set the country’s course to become a member of the European Union and NATO. Later in his life, he also served as minister of defence, a member of parliament, and the leader of the Pro Patria Union. Since 2013, he’s served as the chairman of the supervisory board of the Bank of Estonia.

Toomas Hendrik Ilves

Born in Sweden and grown up in the United States, Toomas Hendrik Ilves’s involvement with the Estonian independence movement started many years before the sovereignty was officially restored in 1991. Working at Radio Free Europe – a Munich-based, US-funded anti-communist news source – he became the head of the station’s Estonian desk in 1988, the year of the Singing Revolution.

He started to participate in the new democratic movements of the country of his parents and in 1993, Lennart Meri asked him to become Estonia’s ambassador to Washington. There, as well as an Estonian foreign minister later in the decade, he played a major role by convincing various Western movers and shakers that Estonia has reoriented decisively towards the West and is eager to join first the European Union and second, NATO (as it happened, Estonia managed to join the both in 2004.)

Foreign policy aside, it was another field that would years later also define his presidency: digitalisation. Inspired by his own experience as a young programmer, Ilves proposed the Tiger Leap project – which involved investing in the development of computer infrastructure in Estonia, with a particular emphasis on education. In 1996, the Tiger Leap project got the green light and soon snowballed: all Estonian schools gained internet connections and most had computer labs installed too.

Elected president in 2006, Ilves became one of the principal global spokespersons for this newly-confident, digital Estonia that also became a hotbed for startups. It is fair to say that internationally, no Estonian politician has stood out as brightly before or after Ilves – not yet, anyway.

Marju Lauristin

The Grand Old Lady of the Estonian politics, Marju Lauristin’s influence in the Estonian society is impossible to overestimate. Not only is she one of the heavyweights in the politics, but she is also a social scientist whose thoughts and lectures at the University of Tartu as a professor have helped shape generations of Estonian journalists and thinkers.

Her family history is controversial – her father Johannes Lauristin was a communist who was appointed in charge of Estonia by the Soviet Union shortly after occupation in 1940. But Marju Lauristin is not “like father, like daughter”. In 1988, she was forming a forceful duo with an Estonian politician Edgar Savisaar at the helm of the Popular Front, the first large-scale independent political movement in Estonia since the beginning of the Soviet occupation.

It was Lauristin who played a major part in formulating the goals and ideas of the movement and she was also very successful at being a calming and moderate voice between the radical Estonian ethnic Russians who were fiercely against an independent Estonia, and more extremist Estonian nationalists. Lauristin’s actions helped calm tensions.

Lauristin’s later career saw her working as the deputy speaker of the Estonian parliament and as the minister of social affairs, while throughout the decades she has been a thoughtful voice in the Estonian political arena. In 2014, at the age of 74, Lauristin stood as a candidate to the European Parliament. TV ads saw the agile and vigorous Lauristin jump on a motorbike and call everyone to “come along to the European Parliament”. Almost 20,000 votes took her there indeed.

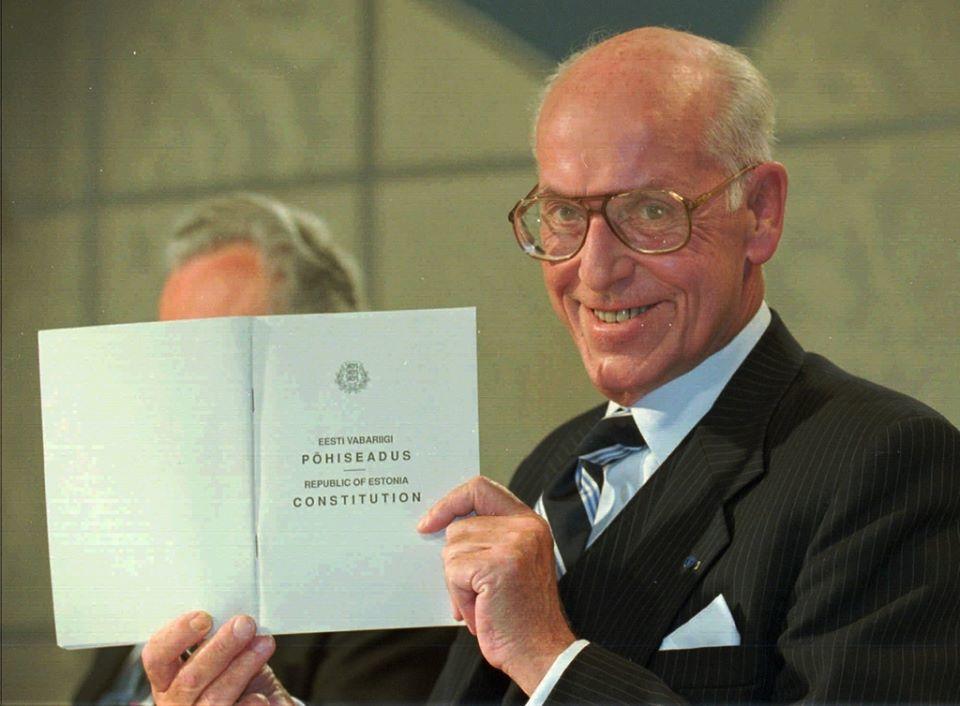

Jüri Adams

It would be hard to overestimate Jüri Adams’ contribution to the Estonian statehood after the Soviet occupation. The politician played an active part in the underground movement and the secret free press, having in 1978 founded a censorship-free underground magazine, “Additions to the free distribution of thoughts and news in Estonia”. Notably, he translated into Estonian the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (the infamous pact that in 1939, carved Europe in half between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union).

He can also be called one of the founding fathers of the present Estonian constitution – between 1991-1992, Adams was a member of the Constitutional Assembly of the newly-restored Republic of Estonia and one of the main authors of the constitution that is still in effect in the country. He also served as a member of parliament (which he still is), as a minister of justice and in the Congress of Estonia. He left politics in 2003, only to return in 2015 as an MP.

Tunne Kelam

Now a member of the European Parliament for 12 consecutive years, Tunne Kelam played a crucial role in restoration of Estonia’s independence. Already in 1972, he prepared a memorandum to the United Nations, asking for assistance to remove Soviet forces from Estonia and organise free elections. He also organised underground opposition groups and passed information to the West about human rights violations in the Soviet-occupied Estonia.

By the end of the 1980ies, he had become one of the leading advocates for restoration of independence. In 1988, he was one of the founders of the Estonian National Independence Party, in 1989 he emerged as one of the leaders of the Estonian Citizens’ Movement, and in 1990, he was elected to the Congress of Estonia. In August 1991, he was instrumental in achieving a national understanding with the Soviet Estonia’s Supreme Council on the principles of restoring the country’s independence.

In later life, he always remained active in politics, serving in the parliament and holding the reigns of the Pro Patria Union, a centre-right political party, before being elected to the European Parliament.

Siim Kallas

In 1987, with the increasing political freedom in society, Estonians started demanding economic reforms and the right to make their own decisions. Kallas (who by that time was mainly known by leading the popular Sunday morning quiz show, called “Mnemoturniir”, on the Estonian radio) joined with three other masterminds – government official Edgar Savisaar, scientist Mikk Titma and journalist Tiit Made – and proposed self-managing Estonia (the Estonian acronym IME stands for “miracle”). The plan was to make Estonia economically independent from the Soviet Union – adopt a market economy, establish Estonia’s own currency and tax system. The idea met an enthusiastic discussion in the society and was the start of a long political career for the initiators (except Titma, who chose to stay away from politics.)

After Estonia restored its independence, the country’s economy was in tatters and the inflation was going through the roof, as the country was still dependent on the Soviet ruble. The advancement to reintroduce Estonia’s own currency, the kroon, was slow to come. Kallas, who had already made a name for himself as an efficient executive, was offered to take the helm at the Estonian central bank to kick-start the progress. Taking over the Bank of Estonia, which only employed 11 people at the time, he quickly established a coherent structure and less than a year later, in June 1992, Estonia brought back into existence the independent currency, after a break of over 50 years.

Always restless and looking for a new challenge, Kallas was eager to enter politics and in 1994, he and a group of well-known business and media figures, established a new entrepreneur-friendly political entity, the Reform Party. Starting in 1999, the party was in the Estonian coalition government for 17 years in a row. As prime minister in 2002-2003, his government finalised negotiations, which had been started under Mart Laar’s cabinet, to join the EU and NATO.

When Estonia joined the European Union in 2004, Kallas became the country’s first top European official, assuming an EU commissioner post in Brussels, where he remained for the next 10 years. In 2016, while indicating that he is the best leader to deal with the new challenges that the country faces in coming years, such as shrinking and ageing population and lack of economic growth, he announced his candidacy for the president of Estonia, but ultimately lost.

Liia Hänni

A former politician and an established astrophysicist, Liia Hänni was one of the most significant women in the independence movement of the newly-restored Republic of Estonia. In 1990, she joined the Estonian Rural Centre Party, a centre-right political movement that later merged into a centre-left party that by today has become the Social Democratic Party. She also participated in the activities of the Congress of Estonia and in 1992, she was elected to parliament. Hänni also took part in the Constitutional Assembly and later on was a member of the constitutional committee of the country’s parliament.

During Mart Laar’s first government, Hänni served as the reform minister – and Estonia badly needed reforms. Laar has later written in his memoirs that despite the immense pressure and occasional public backlash against the reforms, Hänni stood calm and resolute – and just got on with her job.

She has published numerous scientific articles and written extensively about the privatisation of industry and the early reforms that took place in the beginning of the 1990ies. Presently, she serves as the senior expert on e-democracy at the e-Governance Academy.

Andrus Ansip

Andrus Ansip’s meteoric rise to become prime minister in 2005 surprised many – after all, he had just left his job as a mayor of Tartu and had assumed his first ministerial post a year before. He eventually surprised even more people by becoming the longest-serving Estonian prime minister, governing for almost 10 years. Prior to that, the governments and prime ministers changed usually in every two years or so. Yet, Ansip somehow managed to keep it all together. His critics say that he lacked a grand vision while others compliment him for strong management skills.

He was also skilful at displaying confidence even during the crises – and the public bought it. So much so that even after Estonia’s economic output had fallen by 14 per cent in 2009 due to the global financial crisis and the collapse of a real estate price bubble fueled by cheap and easy credit from banks, the Reform Party – which Ansip led – still won the general election in 2011. As the American author, Justin Petrone, would later write, “we would all know that Ansip was the kind of man who would, say, amputate his own arm should it get stuck under a boulder, and not shed a tear about it, ‘because it made sense and it was the right thing to do’. Estonians have a word, kindel, which can mean “certain” and “secure”. Ansip seemed to embody both meanings.”

It is fair to say Ansip’s government demonstrated a sound management with state finances. Ironically, when the economic crisis of 2008 brought many countries, such as Ireland and Greece, to their knees, Estonia´s global image was strengthened further – here was a country that had been hit, too, but managed to keep its budget balanced. Few years later, Estonia even managed to join the eurozone, the first of the EU states formerly occupied by the Soviet Union to do so.

Siiri Oviir

For long, Siiri Oviir has been one of the most pre-eminent female politicians in Estonia. With a background in law, in 1989 she helped re-establish the Estonian Women’s Union, which she leads since 1996. She was the only female minister in the transformational government, led by Edgar Savisaar in 1990-1992. Oviir was the minister of social affairs and social issues have been closest to her heart throughout her political career. During the harshest times in Estonian society, Oviir was fighting for those who needed help, such as people with special needs, for example.

She assumed the same ministerial role twice later – in the cabinets of Tiit Vähi and Siim Kallas.

In 1991, she became a founding member of the Centre Party – the leading party in the current coalition government – and for many years was one of its leaders, alongside the domineering Savisaar (although like many, who eventually became disillusioned with the party’s leader, Oviir terminated her membership in 2012, after issuing a damning statement.)

During the 1996 presidential election, Oviir was the only female candidate (Lennart Meri won for the second term). She finished her political career as a member of the European Parliament, working in Brussels for 10 years.

Tiit Vähi

An interim leader of the Estonian government during the transitional period (and, later, the third prime minister after the Soviet occupation after Mart Laar and Andres Tarand), Tiit Vähi laid the groundwork for transforming Estonia into a free market economy, having introduced the Estonian Privatisation Agency and overseeing the currency reform that returned to the country its pre-occupation currency, the kroon.

Before assuming the post of the interim leader of the government, he served as the minister of transport and communication, where he forged close ties with the transport ministries of the Nordic countries and improved transport-related ties with Latvia and Lithuania. He’s also credited with transferring control of Estonia’s airports, sea ports and railways from Moscow to the Estonian authorities.

By now, he has left the political scene and works as the chief executive of Silmet, the largest employer in Ida-Viru County in eastern Estonia. He also oversees the construction of the easternmost sea port of the European Union – the Sillamäe Harbour.

Lagle Parek

The minister of the interior in the first post-occupation government (Mart Laar’s first cabinet), Lagle Parek is known more as a dissident during the Soviet occupation of Estonia. She was a political prisoner in a Russian prison camp from 1983-1987 for anti-Soviet activities, where she took part in a hunger strike and other protests, for which she was imprisoned in solitary confinement.

Having been pardoned in 1987, she returned to Estonia and was one of the main organisers of the Hirvepark meeting on 23 August 1987, the anniversary of the Nazi-Soviet Pact. By various estimates it was attended by 2,000 to 5,000 people and was one of the first organised public demonstrations against the Estonian Communist Party, effectively starting the political independence movement. In 1988, Parek became one of the founders of the Estonian National Independence Party, the first non-communist political party in the Soviet Union, also serving as its chairman. She also participated in the Congress of Estonia, and was elected to the first post-occupation parliament.

In 2010, she published her book, “I Do Not Know Where I Get Joy. Memories” where she vividly recalls her life as a dissident, imprisonment and life in the Soviet prison camp. In the 1990s, she converted to Catholicism, and now, she is head of the non-profit association, Caritas Eesti, part of the international Catholic charity confederation, Caritas. She lives in the Pirita Convent.

Cover: Lennart Meri in his presidential Mercedes. * Please note that this article was originally published on 20 August 2017.

Hardo Aasmäe!