About fifteen per cent of Estonia’s population are foreign-born migrants; a recent study looked into the biggest grievances of the foreigners who have decided to settle in Estonia and discovered that in addition to learning the local language, migrants have other issues, too, they’re not completely happy with.

“I came here for four days as a backpacker, arrived hungover from celebrating my birthday in Vilnius the day before, and made the decision to stay here while drunk. I regret nothing!” – anonymous.

In 2020, a grand total of 16,209 people moved to Estonia. In fact, as of 2021, Estonia is home to 199,452 foreign-born migrants who make up a staggering 15% of the country’s population.

Each new migrant has a unique story (let’s just say some are more peculiar than others) yet shares common challenges in adapting to the Estonian way of life. The Integration of the Estonian Society (EIM 2020) survey, co-authored by the Institute of the Baltic Studies, aims to capture these shared experiences to inform policymakers.

Yet, as expected for such macro-level academic endeavours, statistics are prioritised over individual stories. To counteract this feature and gain a deeper understanding of migrant experiences in Estonia, a recent supplementary report analysed a total of 1,166 optional text comments left by EIM 2020 survey respondents. This article highlights a selection of especially salient issues discovered in the process.

From tragic accounts to reassuring declarations

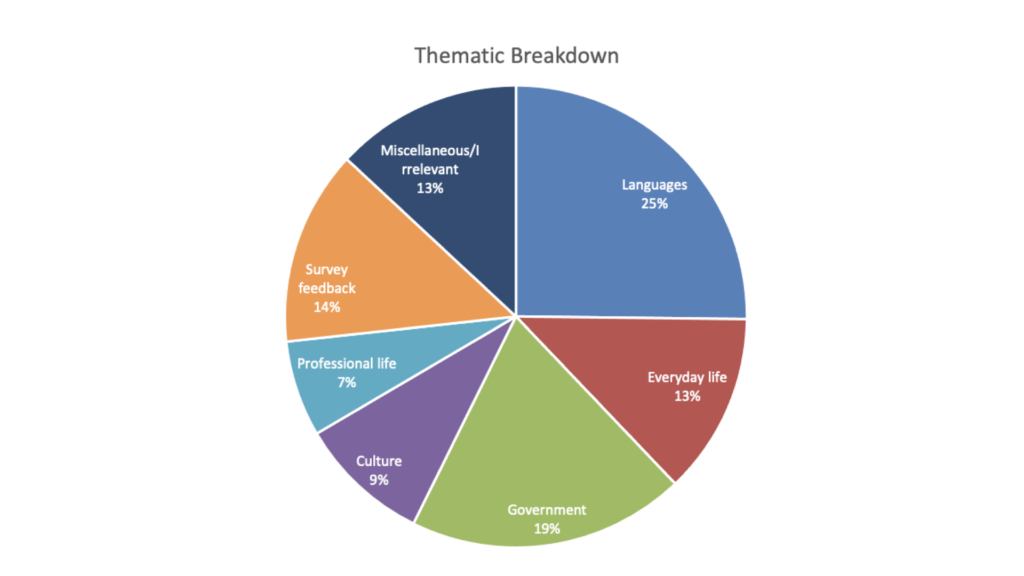

Let’s first take a glance at a few numbers. Gathered from citizens of 85 countries who moved to Estonia within the past decade, the comments ranged from tragic accounts of “hair loss due to the lack of sunlight” to more reassuring declarations – “Estonia’s ok.” This potpourri of qualitative data was coded into seven themes and, among these, 46 subtopics.

The most prevalent concerns came from three themes: language (25%), public services (19%) and everyday life (13%). Learning of the Estonian language, English use in daily life and vague comments (just like the one in the opening of the article) were, in turn, the dominant subthemes.

While sparing you the details on all the numerous sub-categories, it is important to examine some of the principal complaints raised within these themes.

Breaking through the language barrier with government support

Learning the local language is undoubtedly a crucial step of the integration process. Language fluency is a gateway to social, political and economic participation. While the Estonian government sponsors free language courses for migrants, the EIM 2020 survey shows that only 52% of the participants are satisfied with the current provisions – a concerningly low figure.

The comment section shines a light on the causes of this low satisfaction rate. The shortage of sign-up slots was the main issue highlighted by the comments. As one respondent writes, “it feels like as soon as they [the language courses] are made available, they run out of space.”

Some of those who did manage to get a spot complained of low course quality and outdated teaching methods. The “rather traditional learning model” is unsuitable for modern students.

It is clear the current number of language-learning slots is not enough to accommodate the high demand. While expanding the teaching capacity will take time and resources, the rewards for such efforts promise to outweigh the costs.

Dealing with “the elusive family doctors”

Reportedly, “palatable potatoes” and English-speaking family doctors are both few and far between in Estonia (some new private initiatives have started to offer multilingual health advice; please see Minudoc and Salu – editor). This presents a pressing challenge for Estonia.

Some family doctors reject English-language speaking patients, passing them onto their colleagues in a game of administrative hot potato. “I gave up after three years and just visit the emergency room or go to a private doctor,” one respondent wrote.

One solution to the problem could be creating a registry of English-speaking health-care professionals. Of course, the opponents of this solution argue that this move will produce disproportional patient allocation and general chaos. Thus, in the long run, the government should ensure better English training for medical personnel.

Local friendships

As a self-proclaimed nation of introverts, Estonia presents a challenge to even the most socially sophisticated expats. As the survey indicates, only 44% of migrants interact with locals on a regular basis. Most of these contacts take place in formal settings at school or work.

Multiple comments similarly note that Estonians are not particularly eager to establish close friendships. “If you don’t have an Estonian friend already (by some magical ways), it is incredibly hard to make friends,” a respondent commented. Meaningful friendships are thus challenging to establish as “Estonians are very kind but extremely closed.”

While there is little we can do to help the national propensity for introversion, more social events with locals (and perhaps some traditional beverages) can do wonders. More than 40 comments suggested state-organised social events with native Estonians. Some have even proposed a German-style buddy-up programme where local Estonians become guardian angels of sorts for newly arrived migrants.

The dark side of Estonia’s naturalisation policy

Naturalisation, the process of receiving local citizenship, is rightfully considered the pinnacle of integration. Estonia requires all naturalisation applicants to renounce their original citizenship. Unfortunately, as noted by 28 respondents, this condition bars foreigners from about 19 countries that do not provide their citizens with the right to waive their citizenships.

Roughly 34% of the EIM 2020 survey respondents who do not plan to apply for naturalisation cited having another citizenship as the reason. As the comments indicate, a good portion of these respondents might be unable, rather than unwilling, to give up their original citizenship.

To ensure Estonia’s naturalisation policy is fair and equal, the government should provide exceptions to the rigid migration law. In Denmark, for example, citizens who do not have a legal right to give up their first nationality can still apply for citizenship.

Wrapping up on a more optimistic note

Evidently, the process of migrant integration in Estonia has its hurdles, which policymakers should aim to tackle. As the analysis of text comments left by the EIM 2020 respondents illustrates, improvements could be made in multiple areas such as language course provisions or naturalisation requirements.

Nevertheless, it is also crucial to acknowledge the various positive aspects of integration. Ranging from praises of Estonia’s lush nature to commendations of the country’s streamlined bureaucracy, hundreds of these positive comments attest to Estonia’s attractiveness as a destination country for thousands of migrants. The main EIM 2020 survey report has other encouraging statistics that provide a more balanced picture of migrant experience in Estonia.

After all, even an adventurous backpacker who decides to settle in the country on a hangover-induced whim can make Estonia a home. That, if anything, is an indication that we are doing something right!

This is a lightly edited version of the article originally published on the Institute of Baltic Studies web page. Read also: Hesam YR: Could Estonia be home to expats?

The cover image is illustrative. Photo by Mariann Liimal.