Thirty-one years ago, on 28 September 1994, the ferry Estonia vanished into the Baltic Sea, and passenger shipping has never been the same.

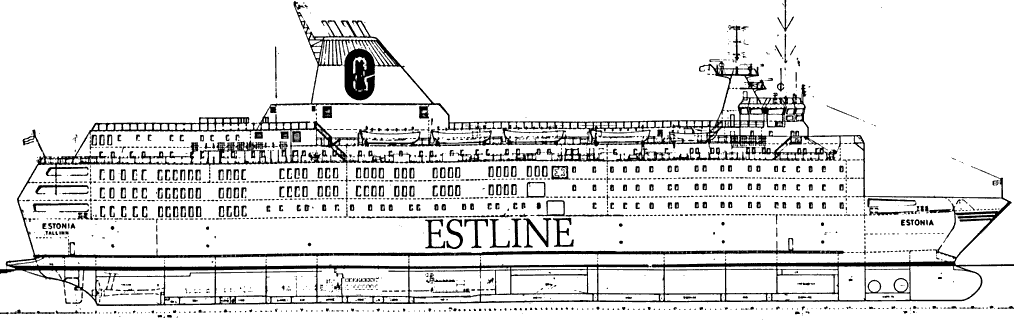

On a late September night in 1994, the ferry MS Estonia left Tallinn for Stockholm and never arrived. Just after one in the morning, in seas that were rough but hardly exceptional for the Baltic, passengers felt a shuddering series of bangs reverberate through the hull. Within an hour, the ship was gone. Eight hundred and fifty-two people drowned. Only 137 survived.

The scale of the loss was staggering, but the shape of it was familiar. Maritime history is punctuated by disasters that remake the very rules of seafaring. The Titanic in 1912 gave the world the first comprehensive safety convention. The Herald of Free Enterprise in 1987 forced regulators to confront the danger of wide, unpartitioned car decks. And then the MS Estonia, whose failed bow visor exposed the vulnerabilities of roll-on/roll-off ferries, spurred another reckoning.

“Major maritime disasters have, throughout history, shaped the development of shipbuilding regulations,” says Kristjan Tabri, a tenured associate professor at Tallinn University of Technology and an expert on marine technology. “The sinking of the Estonia led to numerous additions through the Stockholm Agreement. The most notable of these were the tightening of damaged ship stability requirements under the SOLAS Convention, and the widespread replacement of bow visors with bow doors.”

The night a visor gave way

The bow visor – a fifty-tonne steel shell designed to swing upward, exposing the loading ramp behind it – was the MS Estonia’s defining weakness. Held in place by three locking mechanisms, it was meant to withstand heavy seas but, as the official inquiry concluded, it could not withstand the repeated battering of waves that September night. Once the visor ripped free, the ramp gaped open, and water poured onto the car deck.

The efficiency of roll-on/roll-off ferries lies in their design: vehicles drive on and off in minutes, making them ideal for Europe’s short sea crossings. But the design is also treacherous. A flood on the car deck acts like a free weight shifting inside the ship, stripping it of stability almost instantly. Survivors of the Estonia recalled the sudden, irreversible list to starboard that made movement impossible, doors and stairways vertical, escape routes meaningless.

The storm that night was not extraordinary. What was extraordinary was how quickly the vessel succumbed.

From Titanic to Estonia: rules written in grief

If the sea is relentless in its indifference, regulation has always been reactive, written in the aftermath of catastrophe. The Titanic’s 1,500 dead produced SOLAS – the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea – requiring lifeboats and setting buoyancy standards. By the mid-20th century, the conventions had extended into damaged-ship stability, establishing for the first time a mathematical threshold: a minimum metacentric height for vessels even after sustaining damage.

The logic deepened over time. By the 1960s, engineers began applying probabilistic methods, estimating how different configurations of damage might affect a ship’s ability to stay afloat. These rules worked well enough for conventional passenger liners, which lacked sprawling vehicle decks. They were not written for ferries designed as floating garages.

The Herald of Free Enterprise capsized in 1987 within minutes of leaving Zeebrugge, its bow doors still open. That disaster forced regulators to reckon with the unique risks of the ro-ro form: the great, undivided car deck. SOLAS 90 followed – stricter freeboard, bans on fully open decks, management codes obliging crews to check what had once been left unchecked.

The MS Estonia sank the same year those reforms were finally codified. It became the grim proof that they had not gone far enough.

The Stockholm Agreement

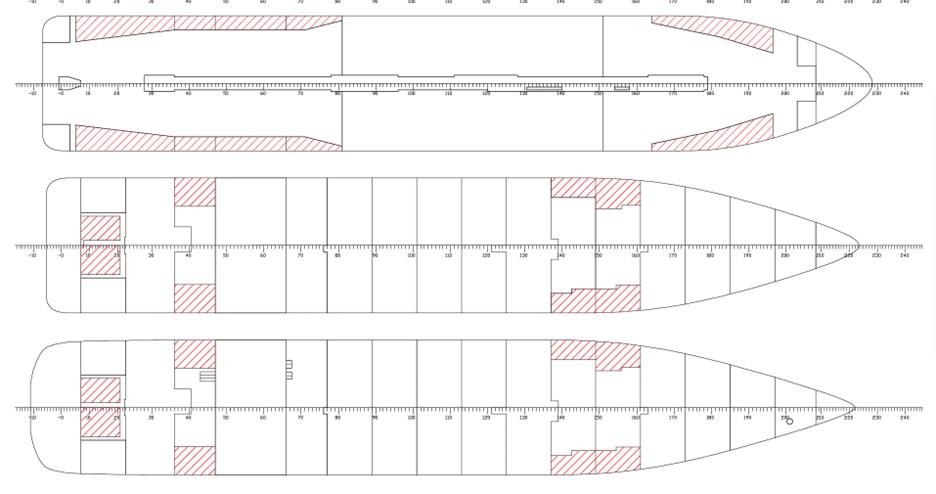

In 1996, European states reached the Stockholm Agreement, which pushed the logic further. It required that ro-ro passenger ferries comply with SOLAS 90 standards even when half a metre of water is already on the car deck. The assumption was simple: ferries must be able to survive conditions that had doomed the Estonia.

That requirement forced a quiet revolution in ship design. New vessels were built with subdivision in mind: longitudinal bulkheads narrowing the sweep of the car deck, watertight partitions beneath it, tanks designed to counteract a list. Hulls were widened with sponsons, giving ships a broader stance against the sea. Older vessels faced expensive retrofits or retirement.

“The requirement meant that water could no longer be allowed to spread freely across the car deck,” Tabri explains. “Either its entry had to be limited, or its movement restricted. For older ships, this was an immense technical and financial challenge.”

The result was not perfection – no engineering ever is – but a vessel that could absorb damage and flooding without surrendering immediately.

The other legacy of the Estonia is visible in every ferry bow. Upward-opening visors, once the standard, have almost disappeared from open-sea routes. Their flaw is structural: waves press side-opening bow doors closed, but they strain visors open, pounding their locks with every cycle of force. Predicting the limit of those stresses is nearly impossible, as Tabri notes, “because the sea is statistical, chaotic.”

By the late 1980s, shipowners had already begun welding visors shut and replacing them with side-opening doors. After 1994, the change became near universal. Today, visors survive mainly on short coastal routes, such as those linking Estonia’s islands to the mainland. Out in the open sea, they are relics.

Safer ships, lasting scars

The story of the MS Estonia is, in part, a story of technical adaptation: stronger standards, redesigned hulls, abandoned visors. It is also a story of how the sea resists complacency. Each time the industry imagines that the rules are settled, another wreck rewrites them.

For survivors and the families of the 852 who died, these reforms arrived too late. The ferries crossing the Baltic today are safer because of what was learned, but the human cost remains incalculable.

Tabri’s view is unsentimental but clear-eyed. “These disasters are part of a chain. Each tragedy forces us to confront weaknesses. The MS Estonia made today’s ferries safer – but at a terrible cost.”

That is the paradox of maritime safety: the lives saved are invisible, the lives lost unforgettable. The Baltic holds the MS Estonia in silence, her wreck sealed on the seabed. Above the surface, every ferry sliding out of Tallinn harbour carries her legacy – a reminder that progress at sea, as on land, is never free.

The legacy of MS Estonia

- The disaster (1994) – in the early hours of 28 September, MS Estonia sank in the Baltic Sea. Within an hour, 852 lives were lost, making it one of Europe’s deadliest maritime tragedies.

- The inquiry (1997) – a trilateral investigation by Estonia, Finland and Sweden found that the bow visor’s failure allowed flooding of the car deck, destabilising the ship and causing it to sink.

- Regulatory turn – the 1996 Stockholm Agreement and subsequent SOLAS amendments tightened stability standards, compelled retrofit work on older ferries, and precipitated the widespread discard of bow visors in favour of bow doors.

- New scrutiny (2020) – a Swedish documentary captured imagery suggesting a large hole in the wreck’s hull. Its release rekindled debate – was the damage caused by an external force, or the ship’s own collapse on the seabed?

- Revelations and debate (2022) – reports surfaced that Swedish defence forces had reportedly transported more military equipment aboard MS Estonia than originally disclosed, renewing public suspicion and calls for deeper forensic study.

- Today – thirty-one years on, the wreck remains on the seabed, its silent presence overshadowed by the safer ships and stricter regulations above. Investigations continue, but many families still wait for fuller clarity.