Estonia’s digital nation likes clean stories: a borderless ID, thousands of new firms, and a record €125 million for the treasury; the messier truth is that much of the gain is concentrated, partly time-driven – and a long way from the early dream of 10 million e-residents.

Estonia’s e-Residency programme is enjoying a vintage year on paper. A government press release says that in 2025 e-residents founded 5,556 new companies – up 15 per cent on 2024 – and delivered nearly €125 million in “direct revenue” to the state, an 87 per cent rise year on year. Officials add a flourish: for every euro invested in e-Residency, Estonia got more than twelve back.

It is, at first glance, the sort of clean, modern success story Estonia likes to export: a digital nation minting tax receipts from entrepreneurs who may never set foot in Tallinn. Look a little closer and the picture becomes more complicated – not necessarily less impressive, but less straightforward than the headlines suggest.

And by the programme’s own early moonshot standards, it also remains smaller than once imagined: e-Residency was at times framed as a project that could reach 10 million e-residents. Even allowing for the rhetoric of the era, today’s reality falls well short.

A record boosted by a tax deadline

The €124.9 million figure is largely tax. The release breaks it down as €54.5 million in labour taxes, €66 million in corporate income tax on distributed profits (mostly dividends), plus roughly €4.3 million in state fees from applications and company registrations.

Those numbers are plausible, and they align with how the programme has reported impact in recent years. The problem is the dramatic jump. A significant slice of the 2025 “record” was inflated by timing, not just growth.

Estonia raised its dividend tax regime, removing a previously lower rate for regular pay-outs. Predictably, many companies accelerated dividends into early 2025 to lock in the old treatment. That front-loading boosted corporate tax receipts, and even programme officials have acknowledged as much. Revenues remained robust after the initial spike, but the surge means the headline figure is not a clean measure of steady-state performance – and the growth rate is unlikely to repeat once behaviour normalises.

What, exactly, counts as “e-Residency impact”?

There is also the question of attribution. Estonia uses a government-approved model that counts taxes and fees from companies tightly linked to e-residents: firms founded by an e-resident, or where an e-resident becomes an owner or board member within 90 days of the company’s establishment. The rule is designed to be conservative – to avoid claiming credit for businesses that would exist in Estonia anyway.

The National Audit Office has previously reviewed and accepted the methodology, and that matters. Yet the model has a built-in limitation: the e-Residency team cannot identify which specific companies generated the tax totals. Privacy rules mean tax data arrives aggregated, not itemised. That makes independent verification hard. It also leaves a grey zone: the model may be conservative, but the public must still take on trust the claim that these revenues “would not” have flowed to Estonia without e-Residency.

Journalists have pointed out the obvious stress test. If a sizeable company operating in Estonia happens to have a foreign executive who holds e-Residency, its taxes could be swept into the programme’s “impact” – even if the business has nothing to do with e-Residency’s promise of borderless entrepreneurship. Officials argue such cases are limited and the 90-day rule reduces noise. Without granular visibility, outsiders cannot meaningfully audit that assertion.

The long tail: thousands of firms, few taxpayers

A second caveat is concentration. Tens of thousands of companies have been founded by e-residents since 2014, but only a minority appear to generate substantial activity – and a smaller minority pays serious tax.

Officials have said that out of the broad universe of e-resident firms, only around 2,000 paid any taxes in a recent year. Past programme figures suggest roughly 29,000 companies had been started by early 2024, about 22,000 still existed, and only about half were “active” in any meaningful sense. In other words: e-Residency creates a long tail of micro-companies, dormant entities and short-lived experiments, while the state’s revenue is likely carried by a much narrower group of successful businesses.

That does not invalidate the programme. It simply changes how to read it. Averages can mislead. If only a fraction of firms pay tax, the average contribution per tax-paying company looks hefty – which usually signals a skewed distribution: a few high performers, many small consultancies and a large remainder doing little at all.

Risks the press release doesn’t mention

Press releases are not designed to enumerate downside. But e-Residency’s vulnerabilities are not footnotes – they are central to its political sustainability.

Illicit finance and reputational exposure. Estonia’s Financial Intelligence Unit has repeatedly warned that easy digital access to company formation carries money-laundering and sanctions-evasion risks. Estonia has tightened screening over the years and, after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, suspended new applications from Russian and Belarusian citizens. These are not optional bureaucratic flourishes; they are the price of keeping partners and banks confident that e-Residency is not a back door.

Economic substance. The release boasts that e-residents account for about one fifth of new company founders in Estonia. That is striking — but many of those firms exist mostly on paper in Estonia, run from elsewhere with local service providers handling compliance and registered addresses. Labour taxes are real, yet the press release does not explain how many jobs sit behind the €54.5 million, nor how much payroll activity is genuinely anchored in Estonia rather than abroad.

Transparency and accountability. Because the programme relies on anonymised tax data, the public cannot see the composition of its “impact” – which sectors, what scale of firms, what share of revenue comes from a handful of outliers. Even if privacy constraints are legitimate, the effect is to weaken scrutiny at precisely the moment the programme is scaling and marketing harder.

The next leap

The state spent about €10 million on e-Residency in 2025. By the programme’s own maths, the return is still comfortably positive. But scaling is not just a marketing problem; it is a trust and systems problem.

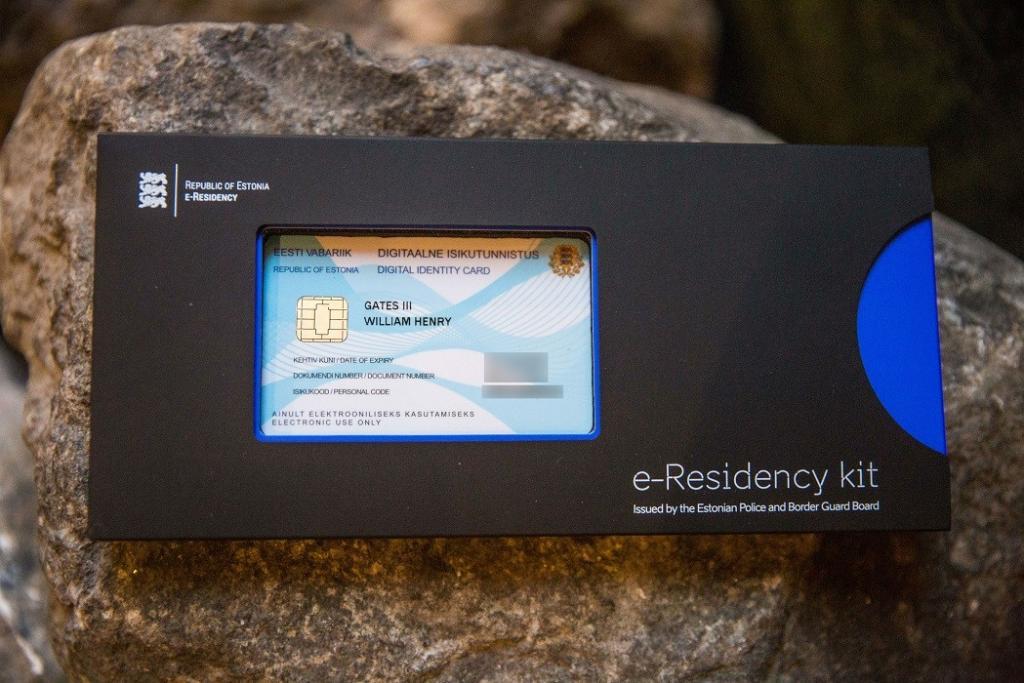

Estonia intends to make e-Residency “cardless”, shifting from a physical ID card (collected in person and used with a reader) to smartphone-based onboarding with remote identity verification. That could cut friction dramatically and boost uptake. It could also widen the attack surface if remote verification is not watertight. The physical card was cumbersome, but it baked in a high-confidence identity step. A mobile-first system will live or die by cybersecurity, fraud controls and the credibility of remote biometrics.

None of this is an argument that e-Residency is failing. On the contrary, it has matured into a meaningful, if modest, revenue stream: €125 million is material, but against a national budget of roughly €15 billion it remains a small fraction, not a fiscal revolution. Its wider value – demand for Estonian legal, accounting and virtual office services; a global community invested in Estonia’s digital brand; a soft-power halo – is real, even if hard to monetise.

The more interesting story is that e-Residency has entered its second decade facing a classic Estonia problem: the country is good at building elegant systems, but it operates under a permanent microscope. Growth brings attention; attention brings scepticism; scepticism brings compliance burdens that can choke the very frictionless appeal the programme sells.

So yes, 2025 looks like a banner year. But it comes with an asterisk: some of the “record” was boosted by a one-off rush to pay dividends before a tax change, much of the revenue is likely coming from a relatively small number of companies, and the programme’s credibility rests on tough, continuous oversight – especially as Estonia shifts to fully remote, app-based issuance. The real test now isn’t how many new users e-Residency can attract, but whether it can grow without the risks growing with it.