Ilon Wikland is an Estonian-Swedish artist and illustrator, renowned for her illustrations for the world-famous Swedish children author Astrid Lindgren.

Born in Tartu in 1930, and raised in Haapsalu, on Estonia’s western coast, Wikland fled from the Soviet occupation of Estonia in 1944 and found a safe haven in Sweden.

A talented illustrator, she applied for a job as illustrator at Rabén & Sjögren in 1953 and was introduced to Lindgren, who had just finished writing the book Mio, my Son and who could see immediately that Wikland was able to “draw fairy tales”. Wikland did a test-drawing for the book and this was the start of the long-term collaboration with Lindgren. Wikland later said Lindgren’s writing made her see inner pictures. In the same way that Lindgren wrote for “the child within her”, Wikland often also drew for the child within her.

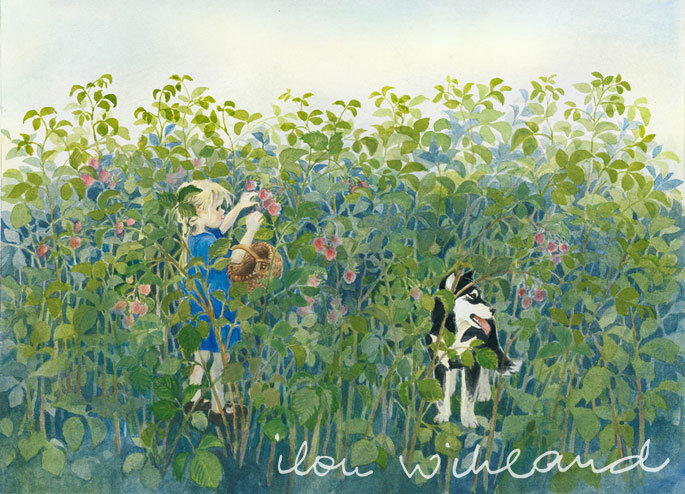

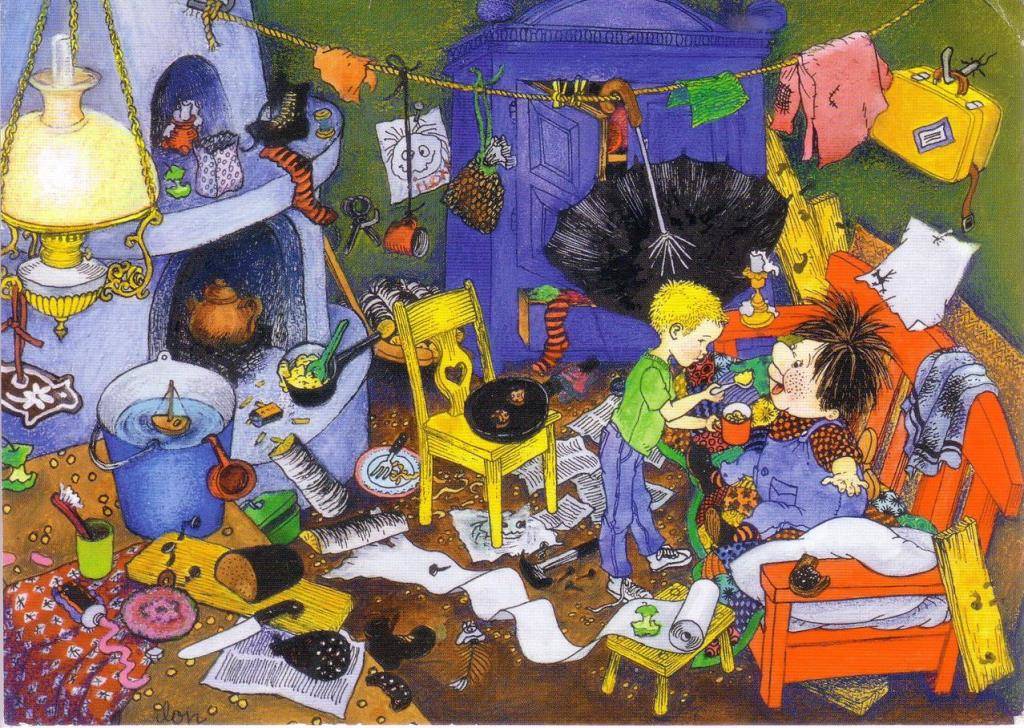

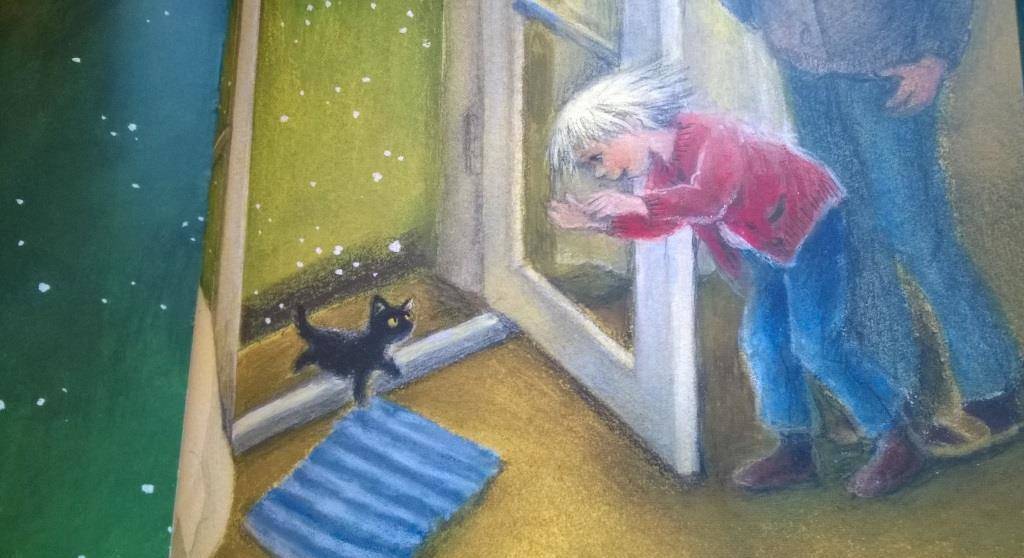

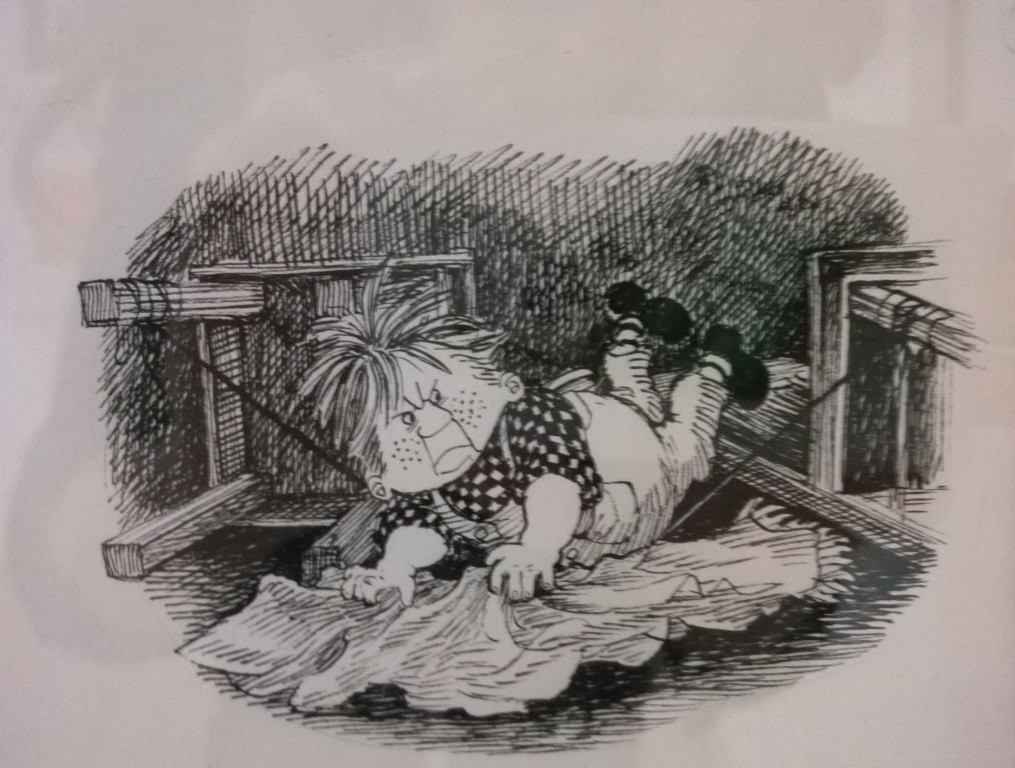

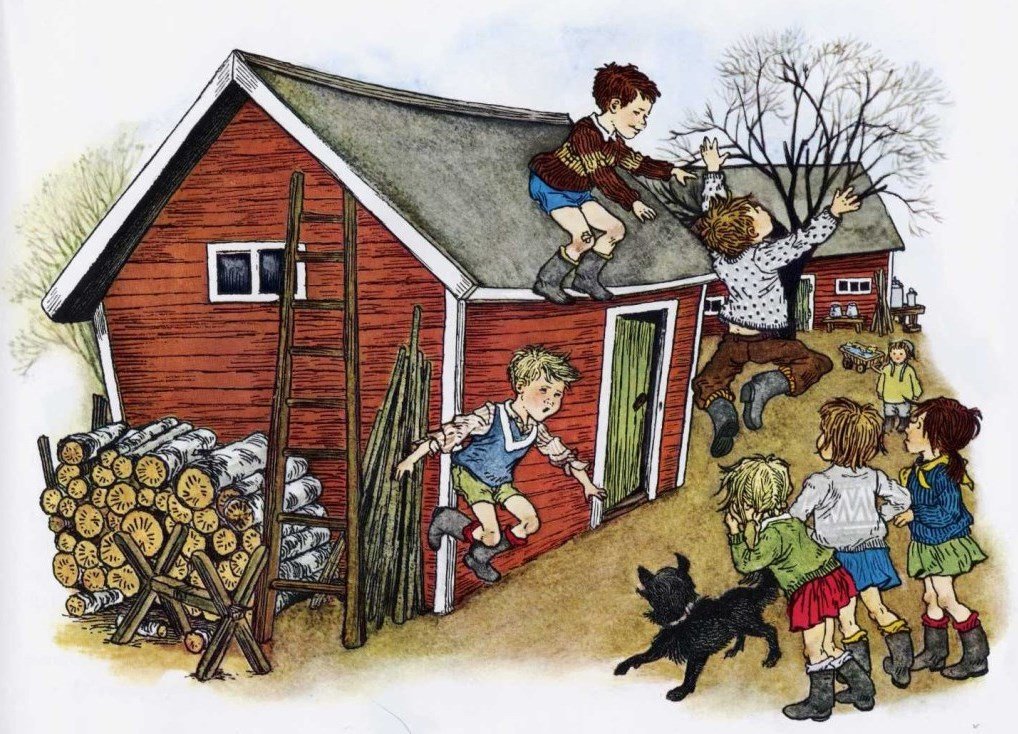

Among other Lindgren’s books, Wikland illustrated The Bullerby Children; The Brothers Lionheart; Karlsson-on-the-Roof; and Ronya, the Robber’s Daughter.

Madli Jõks caught up with Wikland to talk about her grand portfolio.

They’re like old friends to me: Children of Bullerby; Ronya, the Robber´s Daughter; Little Tjorven; and all the others. I know and remember them from my childhood and think back at them as if they had really existed in my life. And, although their stories from Astrid Lindgren were brilliant, I would probably never have been that affected, if the characters had not been brought to life by the magnificent illustrations of Ilon Wikland. I remember looking at the pictures again and again, trying to figure out which exact moment from the story was on every one of them.

Now I had an amazing opportunity to meet all of my childhood favourites in original at Ilon Wikland’s jubilee exhibition in Berlin at LesArt, the Berlin Centre for Children’s and Youth’s Literature.

Wikland, widely known and recognised children’s books’ illustrator, was born in Estonia in 1930 and spent her childhood in Haapsalu, but moved to Sweden as a war refugee at the age of 14. However, tragic destiny led to lucky chance: in Sweden, nine years later she met Astrid Lindgren, who became her dear friend and a work partner for decades.

Illustrations for Lindgren’s books are the ones Wikland is mostly known for, but she has also illustrated books of several other authors (for example Ann Mari Falk, Marlen Haushofer, Hans Peterson), and even fairy tales from Hans Christian Andersen and brothers Grimm, as well as some non-fiction books. Now 85, she is still active and from 2005 onwards, she has cooperated with children’s books’ author Mark Levengood.

At the exhibition in LesArt, more than 150 Wiklands works – drawings, aquarelles and pastels – can be seen. In addition to the illustrations, free drawings and fashion sketches are presented. This is the first Wikland’s overview exhibition in Germany.

Harry Liivrand, the Estonian cultural attaché in Berlin, writes in the exhibition brochure that the most important goal of the exhibition was to bring out the autobiographic background of Wiklands works – to emphasise the elements of Estonia and Haapsalu that are often depicted in her works. The Estonian ambassador to Berlin, Kaja Tael, adds that the idea to bring Wikland’s exhibition to Germany was born from the knowledge that the Germans share Estonian love for Lindgrens’ books.

For me, visiting the exhibition felt somehow more than just visiting an art exhibition – it felt like meeting a part of my childhood again. And the pictures were still as great as they were back then. I walked from one exhibition room to another, a smile in my face, marvelling at the preciseness of the paintings and the naturalness of the characters.

As a grownup, I understand why I admired the pictures as a kid and preferred books with them to all the other ones: Wikland doesn’t cheat. The characters, the rooms and other objects in the pictures look like they looked in the story, details are right and interesting. Wikland understands that children are the most attentive audience.

Wikland says that before drawing, she always reads the text several times very carefully and only when she understands it very well, she begins to draw. “The text is most important,” she says.

It seems to me that for a great artist as she is, she has surprisingly little ambition to interpret things in her own way. But the willingness to work with the author has probably made her that great as an illustrator. And perhaps this is why a child, looking at her pictures, never has to be disappointed about how the characters or a scene looks like.

When I ask Wikland about her relationship and cooperation with Lindgren, which lasted for 40 years, she also emphasises the great understanding between them about the content of the story. “We always talked everything through and she was very willing to answer all of my questions. Our cooperation with Astrid was really smooth and it was a beautiful and good time,” she recalls.

In those 70 years Wikland has worked as an illustrator, has there been one book that she would bring out as a favourite or a very special one? Without a second hesitation she answers: this would be Lindgren’s Brothers Lionheart. “It’s a very important book to me and I like the story very much – it contains a lot of topics, that in my opinion, a child has to learn to understand.”

Wikland’s style has developed a lot over time. Her first illustrations were black and white graphical works, later she mostly used watercolours and pastels. Wikland says that the depicted characters became livelier as time moved on. She thinks that in her earlier works it was noticeable that back then she had no children of her own yet.

She says the cooperation with Levengood has given her the opportunity to develop a new direction. “I find it very important to constantly change and evolve my drawing style. You can’t draw the same way all the time,” says the grand lady of illustrations, who could have given up trying to be better decades ago, and still be an absolutely excellent illustrator.

I have always thought that pictures like Wiklands’ have to be drawn with an intention to show the world as a child sees it, but Wikland says that she has always drawn just the way she herself likes it.

I have always thought that pictures like Wiklands’ have to be drawn with an intention to show the world as a child sees it, but Wikland says that she has always drawn just the way she herself likes it.

Maybe she is just one of those lucky people who haven’t forgotten how the world looks like for a child. Although, her own childhood wasn’t an easy one at all. The divorce of her parents and the leaving of her mother, escaping to Sweden alone on a refugee ship and a serious illness were the challenges she had to live through as a child.

Wikland says that Lindgren probably understood what kind of life experience she had gone through, and her desire for a secure childhood reflected in her drawings.

Can the illustrator herself explain why so many people find her style that touching? “All along, I’ve been trying to paint emotions,” she says, “So that a person, looking at my paintings, could see the feelings.” And this is probably the very answer.

I

Find out more about Ilon Wikland from her web page. Estonian World thanks Estonian Embassy in Berlin for their help in bringing this article to you. Cover: Ilon Wikland (photo by Priit Simson/Eesti Päevaleht).