In a world where music often speaks louder than words, Arvo Pärt’s compositions resonate with a profound, almost spiritual clarity. His minimalist approach to music, characterised by hauntingly beautiful harmonies and a meditative silence, not only redefines the classical genre but also invites listeners into an intimate dialogue of love and transcendence. This story delves into the essence of Pärt’s unique soundscape, exploring how his work encapsulates a deep, universal yearning for connection and understanding.*

This article was published in collaboration with Life in Estonia magazine. By Immo Mihkelson and Silver Tambur

Estonians are proud of Pärt because he is a world-famous Estonian. Fame creates respect. But when we look more closely, his compositions address everyone, attempting to appeal to that shared aspect of human kind which rises above nationality, skin colour and culture. It is as if the music wishes to say that we are all in it together. Pärt commands respect and admiration from classical music fans from around the world.

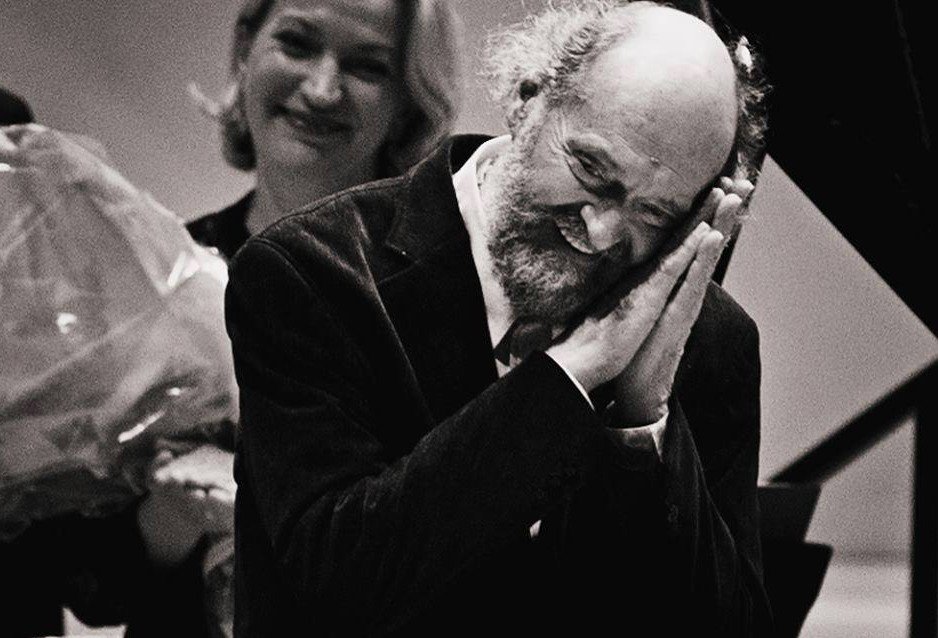

Recent years have been especially successful for the maestro. Pärt has been given the title of the world’s most performed living composer by the classical music event database, backtrack.com, for many years in a row. Conductor Tõnu Kaljuste won a Grammy Award in the Best Choral Performance category for his work on Pärt’s album “Adam’s Lament” at the 56th Annual Grammy Awards in Los Angeles.

In addition to multiple performances around the world, Pärt’s music was in 2014 performed at four sold-out concerts in the United States – two in Washington, DC, and two in New York City, including one at the world-renowned Carnegie Hall, which was also honoured by the maestro’s own attendance.

In October 2014, the Japan Art Association presented Pärt with the prestigious Praemium Imperiale cultural award. The award is considered equal to the Nobel Prize in the field of culture, and was presented to the Maestro by the patron of the association, Prince Hitachi of Japan.

A new theatrical production premiered at the Tallinn’s Noblessner Foundry in 2015. For “Adam’s Passion”, Pärt and American theatre visionary Robert Wilson came together to create a mesmerising symbiosis, combining Pärt’s music and Wilson’s stage choreography with stunning visuals. The stage production also gave a material for no less than two documentaries: “The Lost Paradise” and “Adam’s Passion”.

In November 2017, Pope Francis awarded Pärt with the Ratzinger Prize, designed to honour outstanding individuals for their research in theology and adjacent sciences, or for their religious artwork.

Pärt’s name has become very influential. It stands for music which many people love. Tranquillity, sadness and selfless love emanate from the sounds of that music. It consoles and gives strength.

The road to music

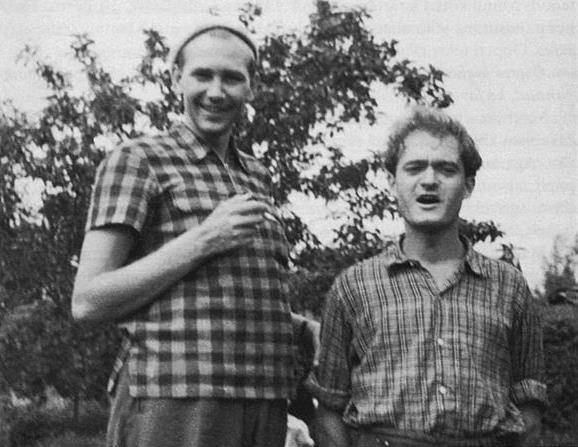

Arvo Pärt was born in 1935, in the Estonian provincial town of Paide, but his parents separated and, before the onset of the war, the mother and son moved to Rakvere. The childhood and early youth of the future composer were spent in the tranquil milieu of that small town. When he started school, the Germans were still in charge in Estonia, but when he commenced his piano lessons at the age of nine, life was lived according to the directions set by the Soviet occupation regime.

Those were restless and anxious times, and left a stamp on many people. When, on Stalin’s command, tens of thousands of people were deported from Estonia to Siberia, Pärt’s close relatives were among them. This left a thorn in his soul and a strong sense of revulsion towards the foreign powers.

The young lad attended school, fooled around with his friends and became fixated on films screened in the local cinema. Music entered his life bit by bit, but from a certain point onwards it overshadowed everything else.

The radio became the focal point of his life: after all it played classical music. On Fridays, live concerts were transmitted and the young Pärt biked to the central square of the town, which had a loudspeaker attached to a post. He used to circle around that post until the end of the concerts. Today the sculpture of a boy with a bicycle on the central square in Rakvere is reminiscent of those occasions.

In fact, this tale is of a person who merged with music from the word go. It is a story of the kind of love and yearning for what’s beyond the horizon, which is often much more emotionally expressed by music than by other arts. And it is also the story of Arvo Pärt’s music – music that many people all over the world feel an affinity with.

The patterns of those melodies call people back into themselves, announce a sense of inexplicable harmony and enable them to be part of or to hope for contact with something much larger. People need it. And this is what Arvo Pärt needed as he followed the call of music throughout his life.

This path was, from the start, full of joy but also twists and obstacles, temptations and suffering. The composer has said in interviews that he does not think his life has differed much from the lives of many others. We share so much with each other: our main needs and our goals are the same. In one way or another, this is what his music is about.

In the draughts of power and spirit

After graduating from school, Pärt went to Tallinn, where the best Estonian musicians and teachers worked. His wish was to become a composer. By then the city had been cleaned up of war ruins, Stalin was dead and a whiff of new-born hope was floating in the air.

In the late 1950s, Pärt’s early works first attracted attention in Tallinn, where they were approved of by older colleagues in the Estonian Union of Composers, and subsequently in Moscow. The times favoured young energy and the socialist society tried to guide it in the “right” direction.

Culture also played a role in the bloodless battles of the Cold War, where competing ideologies tried to prove their supremacy to the masses on the other side. Sometimes it worked. In this confrontation, every talent was seen as a future warrior and Pärt was favoured.

But in Estonia, on the border of the huge red empire, the Iron Curtain was weaker and thus the echoes of modern Western composition techniques could be heard. Pärt became fascinated by them, the more so as they provided the opportunity to express his defiance of the regime. Problems soon developed, as the environment in which Pärt lived considered Western influences to be enemies. Defiance was unacceptable.

Ever since his student-time orchestral work, “Nekrolog” (1960), strong pro and contra draughts had been blowing across his path as a Soviet composer. He was praised, only to be criticised later, persecuted and favoured. Audiences were keen on his music, but the officials had their doubts.

Working as the recording director at the Estonian Radio in the 1960s taught him to listen to the fine nuances of sounds. This job probably also gave him a crash course in the psychology of musicians, which later helped him significantly in making his own special world of sound audible.

Years later, Pärt said that his crooked road of searching for beauty, purity and truth – of seeking God – began in the 1960s. It was the course he chose. Even as a young man, he had high ideals and the intuitive sense that making compromises could lead to losing everything.

Discovering tintinnabuli

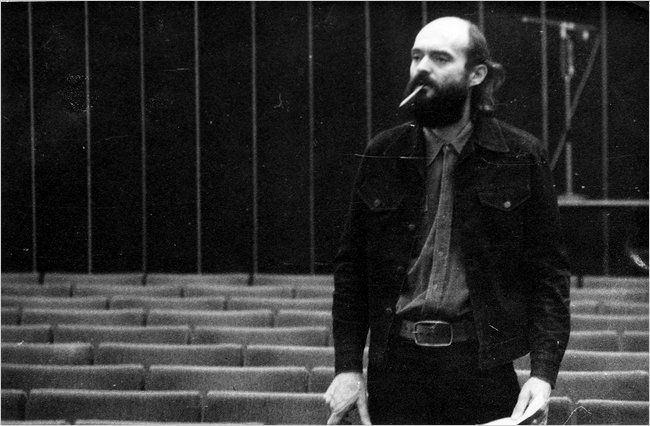

Around 1968, when there was anxiety throughout the world, Pärt lost faith in the contrasts and oppositions of his music. He began to look for a new shape and expression for sounds.

This was a situation in which he had a general sense of what he wanted to say, but he had not yet found the right words, the shapes of sentences and rhythms of speech to express it. Pärt turned to music from earlier centuries and tried to find a way to translate the tranquillity and clarity of that old music into his own language.

This was the great turn that changed his life, both internally and externally. He got married for the second time and moved, living a modest life in a dismal housing estate on the outskirts of Tallinn. The searching years were difficult and those solitary attempts often brought only disappointments. His wife, Nora Pärt, has recalled witnessing her husband almost losing faith and seemingly considering the idea of giving up trying to be a composer.

Then came the spark that changed it all. Born one February morning in 1976, the piano piece “Für Alina” opened a new door and light poured in. Discovering tintinnabuli was a new start for Pärt in music, but the direction of his search remained the same. Tintinnabuli is often mentioned when talking about Pärt’s music. It has been called a method of composing, a unique style and a way of thinking.

There is no simple and clear definition, but many explanations have been offered. Interest in those explanations has grown in parallel with the interest in Pärt’s music all around the world. We do not know if this interest has reached its peak, but we do know for a fact that the music of this Estonian composer has been the most performed contemporary music in the world for several years running.

Universal fame

The call in his music has been slow to reach people, just as the music itself has a slow tempo.

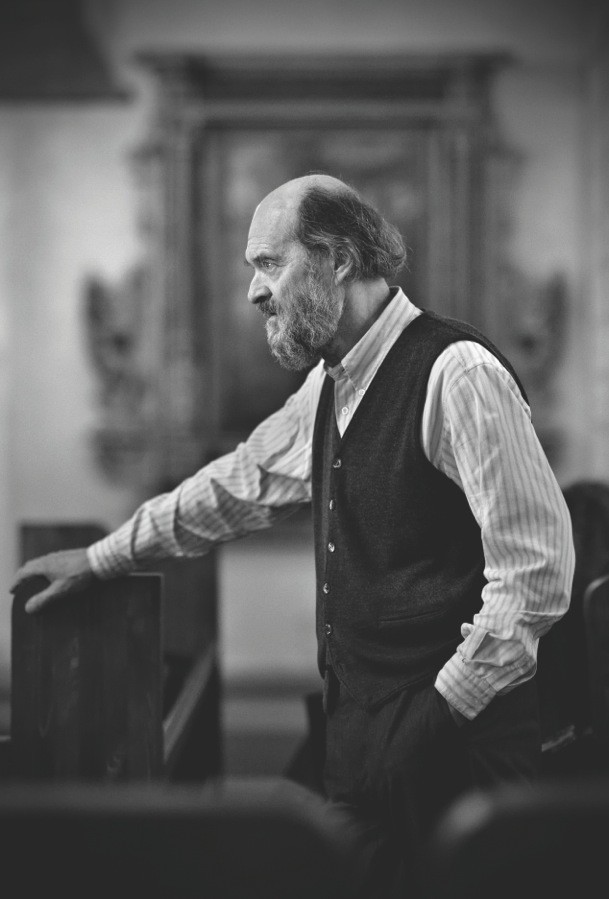

When Pärt left the Soviet Union in 1980 and moved to Vienna with his family, there was nothing positive waiting for him there. The foreign environment made him withdraw ever more into himself and the spiritual world of his music was just as ill-suited for that environment as for the one he had left behind. He wasn’t yet aware of the fact that by chance, a particular German had listened to his music on a car radio in the same year, 1980.

The German in question was Manfred Eicher, the founder of ECM Records. Eichner later recalled that he became so excited that he stopped his car and knew there and then that he wanted to release an album with Pärt’s music. The two men met in Vienna and inspired by the Estonian composer, Eicher established the “New Series” imprint under ECM, the label he founded in Munich in 1969.

When Manfred Eicher and ECM released “Tabula Rasa” in the autumn of 1984, it was a real statement and marked another significant turning point for Pärt. Eicher later said he believed the main piece on the album changed the awareness of music throughout the world in the late 1980s. This may sound a bit pretentious, but many people agree.

The story released by the American press, which has been cited on many occasions, tells of a journalist seeing young men with AIDS, waiting for death in a refugee centre, who listened to Pärt’s “Tabula Rasa” again and again. The sounds must have incorporated something very significant for people dealing with such a serious situation.

All is one

Later many articles asked what it was that pulled people from different parts of the world, people with different skin colours, who spoke different languages and had diverse world-views, towards Pärt’s music.

Many answers have been proposed and, at the same time, his music has been criticised for being light and flirting with listeners. Such comments have come from representatives of modernist music. Such reactions may have been caused by the composer’s clear desire to be on the same wavelength as his listeners, not to tire their perception with sound tangles and structures pushing their limits.

On the cover notes of the album “Tabula Rasa”, there is a beautiful comment by the composer in which he compares his music to white light, which after piercing the prism of the listener acquires different shades. From this angle, all of the elements in this music meet each other: the composer, the musicians and the audience. “Me” and “they” become “us” and things find their natural place. There is balance and order. At least in the ideal world.

Arvo Pärt has said very little to explain his clear and simple music, which aims for unity. The fewer the words, the larger the space to interpret the music. “All is one” and “one and one makes one” are two of the most typical descriptions. The first sums up his world-view generally, and the second describes the unity of the polarities of tintinnabuli.

Music crossing borders

The universe of this music is spiritual and the sounds can be seen as “religious” in a way. People often wonder why Pärt’s music communicates with people regardless of their religious confession or the lack of it, regardless of age or ethnicity.

Perhaps he has been able to translate something very human into sound that crosses the borders normally separating people. We do not know; we can only accept this explanation or offer our own answers.

St Vladimir’s Seminary in the US has founded a research field called the Arvo Pärt Project and, on its website, the seminary claims to attempt to uncover the part of Pärt’s compositions which have been most in the shadow: everything linked to the Orthodox tradition. The seminary was also the organiser of the concerts of Arvo Pärt’s music that took place in Washington and New York in 2014.

Pärt’s “Adam’s Lament” has drawn inspiration from the Orthodox spiritual tradition. Written for choir and orchestra, the piece received acclaim at the Grammy Awards, and the BBC Music Magazine nominated the album containing this piece for its own award ceremony.

Having been kicked out of Paradise, because of sin, the story of Adam is the story of humankind, according to the composer. Pärt uses his music to tell a story that was once written down by Saint Silouan the Athonite. The story was made public by one of Silouan the Athonite’s disciples, Archimandrite Sophrony.

Pärt met Sophrony in the 1980s in Essex, the UK, and he became an important guide for Pärt, perhaps even the most important source of support at that time in his life. The words of encouragement and teachings of Sophrony helped the composer who had relocated to the West to keep up his spirits in the foreign environment and this resulted in a lot of wonderful music.

Pärt started to write the music for “Adam’s Lament” in the early 1990s and Sophrony managed to share his thoughts with the composer before his passing. But then the rough drafts remained in a drawer until a few years ago, when Pärt finalised the work and made it public. He had matured and become wiser by twenty years; he was more experienced as a composer and his sense for life was much deeper.

Whoever listens to the music and tries to touch the sounds and words with his heart, may find a hopeful message in “Adam’s Lament”. This message says that, although many things have turned out badly, each person and humankind as a whole may find their way with the help of love.

This is not the end of the road but just a signpost. A signpost to Arvo Pärt’s music.

Timeline

1935

– Born on 11 September in Paide, Estonia.

1938

– Moved with his mother to Rakvere, Estonia.

1945–53

– Rakvere Music School, piano studies with Ille Martin; first attempts at composition.

1950–54

– Rakvere High School.

1954

– Tallinn Music School, composition studies with Harri Otsa.

1954–56

– Military service at Soviet Army, playing oboe, percussion and piano in the Military Band.

1956

– Continuation of studies at music school, now with Veljo Tormis.

1957–63

-Tallinn Conservatory, composition studies with Heino Eller.

1958–67

– Sound Engineer at Estonian Radio.

Since 1967

– Freelance composer.

1958-68

– First creative period starting with neo-classicist piano music; experiments with serial techniques, aleatoricism, collage and sonic fields. Works like Nekrolog (1960), Perpetuum mobile (1963), Collage sur B-A-C-H (1964), two symphonies (1963 and 1966), Pro et contra (1966).

1968

– Credo, conclusion of his first creative period. In this work the confrontation between two musical worlds – Bach’s Prelude in C Major (WTC 1) and Pärt’s own dodecaphonic music attains its most dramatic expression. An open affirmation of Christian faith caused a scandal in the Soviet Estonia and the piece was immediately banned.

1968-76

– New artistic reorientation. In search of a new musical language, he studied Gregorian chant, the Notre Dame School and renaissance polyphony. Pärt’s long silence was broken only by the Symphony No. 3 (1971), his sole authorised transitional work from this period.

1976

– Für Alina is the first composition in tintinnabuli-technique (tintinnabulum – Latin for ‘little bell’), which inspires his ouvre to this day. The musical material of Pärt’s works is extremely concentrated, reduced to the essential.

1976–77

– 15 tintinnabuli-compositions, including Tabula rasa, Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten, Fratres, Summa.

– Première of Tabula rasa in Tallinn, September 30, 1977 by Gidon Kremer (violin), Tatiana Grindenko (violin), Alfred Schnittke (piano), Tallinn Chamber Orchestra and conductor Eri Klas.

1980

– Emigration to Vienna; contract with the publisher Universal Edition.

1981

– Grant from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), moving to Berlin.

1982

– Passio, commissioned by Bavarian Radio and premiered in Munich by the Bavarian Radio Choir, soloists, instrumental ensemble and organ, conductor Gordon Kember.

1984

– Beginning of the creative collaboration with the CD label ECM and producer Manfred Eicher. Release of the CD Tabula rasa, which launched a whole new series of recordings under the title ECM New Series. Since then all authorised first recordings of major works with ECM.

1985

– Stabat Mater, commissioned by Alban Berg Foundation and premiered in Vienna by the Hilliard Ensemble, Gidon Kremer (violin), Nabuko Imai (viola) and David Geringas (violoncello).

– Te Deum, premiered in Cologne by the Kölner Rundfunkchor, Kölner RSO and conductor Dennis Russell Davies.

1989

– Miserere, commissioned by and premiered at Festival d’Eté de Seine-Maritime, Rouen, by Hilliard Ensemble, The Western Wind Chamber Choir and Instrumental Ensemble, conductor Paul Hillier.

1989-2011

– Eight Grammy nominations, mostly for the best contemporary composition.

1990

– Berliner Messe, commissioned by 90. Deutschen Katolikentages Berlin and premiered in Berlin by Theatre of Voices and conductor Paul Hillier.

1991

– Honorary membership of Royal Swedish Academy of Music, Stockholm.

– Silouans Song, commissioned by Svenska Rikskonserter and premiered in Rättvik, Sweden by Chamber Orchestra of the festival Music at Lake Siljan and conductor Karl-Ove Mannberg.

1994

– Litany, premiered in Eugene, USA, by the Hilliard Ensemble, Oregon Bach Festival Chorus and Orchestra, conductor Helmut Rilling.

1996

– Honorary membership of American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York.

– Dopo la vittoria, commissioned by the City of Milan in commemoration of the 1600th anniversary of the death of Saint Ambrose and premiered in Milano in 1997 by Swedish Radio Choir and conductor Tõnu Kaljuste.

1997

– Kanon Pokajanen, composed for Cologne Cathedral’s 750-year anniversary, premiered in 1998 in Cologne Cathedral by Tõnu Kaljuste and the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir.

1998

– Como cierva sedienta, commissioned by and premiered at the Festival de Música de Canarias in 1999, by Patricia Rozario, Copenhagen Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Okko Kamu.

1999

– Cantique des degrés, commissioned by the Princess of Hanover for the 50th anniversary of the coronation of Rainier III, Prince of Monaco; premiered in Monaco Cathedral by Monte Carlo Opera Choir, Monte Carlo Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Tõnu Kaljuste.

2000

– Cecilia, vergine romana, commissioned by Agenzia Romana for the events of Holy Year 2000; premiered in Auditorium Roma by the Choir and Orchestra of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, conductor Myung-Whun Chung.

– Receives the Herder Prize, Germany.

2002

– Lamentate, for piano and orchestra, subtitled Homage to Anish Kapoor and his sculpture ‘Marsyas’, premiered in 2003 in London, in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall by Hélène Grimaud, London Sinfonietta and conductor Alexander Briger.

2003

– Classic Brit Award – Contemporary Music Award for Orient & Occident

– In principio, commissioned by Diocese Graz-Seckau for the program “Graz 2003 – Culture Capital of Europe” and premiered by choir pro musica graz and Capella Istropolitana, conductor Michael Fendre.

2004

– Da pacem Domine, a cappella work commissioned by Jordi Savall. In 2007 a recording of the piece (in collaboration with Estonian Philharmonic Choir and conductor Paul Hillier; Harmonia Mundi) wins Grammy Award as best choral recording.

– L’abbé Agathon, commissioned by l’Association l’Octuor de Violoncelles / Rencontres d’Ensembles de Violoncelles de Beauvais and premiered in Beauvais by Barbara Hendricks and Beauvais Cello Octet.

2005

– La Sindone, commissioned by Festival Torino Settembre Musica for the Olympic Winter Games 2006 in Turin and premiered in Turin Cathedral by Estonian National Symphony Orchestra and conductor Olari Elts.

– Composer of the Year, Musical America, USA.

2008

– Receives the Léonie Sonning Music Prize, Denmark, and composes These words…, commissioned by Léonie Sonning Music Fond and premiered by Danish National Radio SO and conductor Tõnu Kaljuste in Copenhagen.

– Symphony No. 4, ‘Los Angeles’, premiered in 2009 by Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Walt Disney Concert Hall, USA. The work receives its UK premiere at the BBC Proms in 2010.

– Stabat Mater, new version for mixed choir and string orchestra, commissioned by Tonkünstler-Orchester Niederösterreich; premiered in Musikverein, Vienna, by Tonkünstler Orchester and Wiener Singverein, concuctor Kristjan Järvi.

2010

– Adam’s Lament, commissioned by Cultural Capital Istanbul 2010 and Cultural Capital Tallinn 2011, premiered in Hagia Irene, Istanbul by Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Vox Clamantis, Borusan Istanbul Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Tõnu Kaljuste.

– The Arvo Pärt Centre is established in Laulasmaa, Estonia, which holds composer’s personal archive.

– Celebrations of Pärt’s 75th birthday include three international conferences: „Arvo Pärt and Contemporary Spirituality Conference” at Boston University, „Arvo Pärt: Soundtrack of an Age” at London’s Southbank Centre and „The Cultural Roots of Arvo Pärt’s Music” in The Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre, Tallinn.

2011

– Returns to Estonia where he resides today.

– Classic Brit Award – Composer of the Year for Symphony No. 4.

– Honorary Doctorate of the Pontifical Institute for Sacred Music, Vatican.

– Is elected first ever Academician for Music by the Estonian Academy of Sciences.

– Member of the Pontifical Council for Culture, Vatican.

2012

– BBC’s one-day festival “Total Immersion” in London, dedicated to the music of Arvo Pärt.

– Estonian Music Council Composition Award.

– Prize of the International Festival Cervantino, Mexico.

– Honorary Doctorate of University of Lugano, Faculty of Theology, Switzerland.

2013

– Special program of concerts dedicated to the music of Arvo Pärt held in Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival, 9 – 11 August. Kanon pokajanen, Te Deum, Adam’s Lament, Tabula rasa and Symphony No. 3 were performed among others.

– During the 2013/2014 academic year, Professor of Fine Arts at the University of Tartu. Lectures on Arvo Pärt are given by Professor Toomas Siitan (Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre).

2014

– Swan-Song, new version of Littlemore Tractus for orchestra, commissioned by and to be premiered in Mozart Woche 2014, 29 January, Salzburg, by Wiener Philharmoniker and conductor Marc Minkowski.

– Grammy Award in the Best Choral Performance category for CD Adam’s Lament (ECM).

– Arvo Pärt is the most performed living composer in the world.

– Praemium Imperiale cultural award, Japan Art Association.

2015

– A new production „Adam’s Passion“ based on the music of Arvo Pärt, by Robert Wilson, one of the most well-known American theatre directors and playwrights of avant garde theatre, conducted by Tõnu Kaljuste, premiered in Tallinn, Noblessner Foundry. This spectacle is based on Pärt’s most influential music: Adam’s Lament, Tabula rasa and Miserere, entwined with Sequentia composed specifically for the production.

– Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church Cross of Merit First Class.

– Austrian Decoration for Science and Art.

2016

– ECM released a new album of Arvo Pärt’s music – “The Deer’s Cry” features the composer’s vocal pieces performed by Estonian vocal ensemble Vox Clamantis and conducted by Jaan-Eik Tulve.

– Arvo Pärt received an honorary degree in music from the world-renowned Oxford University in the UK.

2017

– Pope Francis awards Arvo Pärt with the Ratzinger Prize.

– Arvo Pärt honoured by the Romanian president for the special contribution in the arts with the Cultural Merit Order.

– The US northwestern city of Portland, Oregon, held a music festival dedicated to the works of Arvo Pärt.

2018

– Arvo Pärt awarded the Golden Medal for Merit to Culture – Gloria Artis – the highest cultural prize in Poland; in addition, the maestro was given an honorary doctorate by the Fryderyk Chopin University of Music.

– A new, Spanish-designed centre, introducing Estonian composer Arvo Pärt’s creative heritage to both domestic and international visitors, opens its doors in Laulasmaa.

– ECM Records released a new album, “Arvo Pärt: The Symphonies”, featuring all four symphonies by the Estonian maestro.

– “Adam’s Passion”, a unique cooperation by Arvo Pärt and Robert Wilson premieres in Berlin.

2019

– For the eighth year in a row, Arvo Pärt is given the title of the “world’s most performed living composer” by the classical music event database, Bachtrack.

* This article was originally published in partnership with Life in Estonia magazine on 11 September 2015; lightly edited and amended on 11 September 2023.

Brilliance – Vaba Eesti 🙂

Excellent reporting, poetry applied to Hi-Fi journalism…Gracias!

Arvo is so so so GREAT !