Estonia entered 2024 with signs of progress in easing income inequality, yet a quieter, more unsettling shift has taken root beneath the headline figures: more people are slipping into absolute poverty, and a growing share of families say they cannot afford even the smallest of everyday pleasures.

Fresh data from Statistics Estonia shows that 19.4% of the population lived at risk of poverty last year, a modest improvement on 2023. But the absolute poverty rate rose to 3.3%, leaving an additional 8,000 people unable to meet basic needs.

“It reflects income inequality rather than outright deprivation,” said Epp Remmelg, a leading analyst at Statistics Estonia. People at risk of poverty, she notes, are not destitute – but they fall short of the standard of living considered normal in modern Estonia.

In 2024, that threshold sat at €858 in equivalised monthly disposable income. Around 263,200 people fell below it, nearly 11,600 fewer than the year before.

A rare success: elderly Estonians fare better

One group stands out as a genuine success story: older people living alone. Long among the most financially vulnerable groups in the country, they have seen steady improvement.

Among people aged 65 and over who live alone, the at-risk-of-poverty rate fell to 62%, its lowest level in 13 years – a drop of nearly nine percentage points in just one year.

Remmelg attributes this to the steadily rising pension and the fact that more elderly Estonians continue to work later in life. The average old-age pension has been edging closer to wages, strengthening household finances for a demographic that once bore the brunt of poverty statistics.

Families hit hard as benefits shrink and employment dips

The picture darkens sharply for households with children. The at-risk-of-poverty rate among lone parents jumped by 7.4 percentage points in 2024 – a dramatic reversal after generous child benefits in 2023 had lifted many such families above the poverty line.

Last year the trend snapped back. Allowances for large families declined, and a fall in the employment rate compounded the shock. As a result, 38% of lone parent households were again at risk of poverty, alongside 14% of couples with one child and similar levels for those with three or more.

Absolute poverty increased most sharply among the same groups. 11% of lone parent households had incomes below the €346 monthly subsistence minimum. Couples with one child also saw their absolute poverty rate rise to 4.6%.

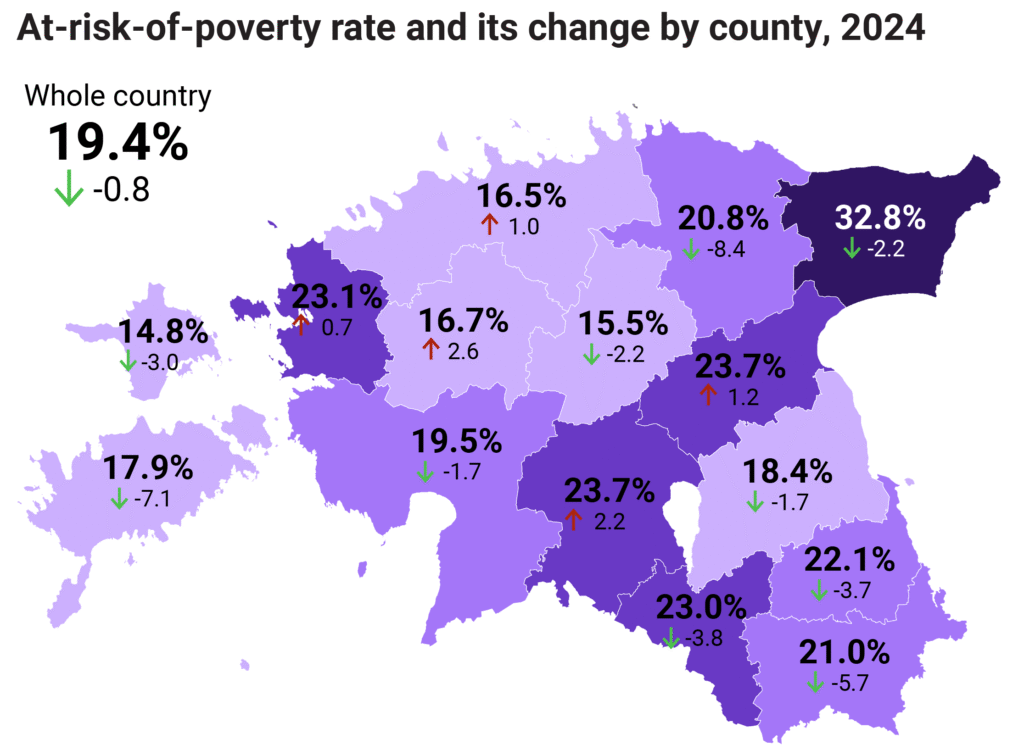

The geography of poverty remains stubborn. Nowhere is the divide more striking than in Ida-Viru County, where a full 33% of residents live at risk of poverty – twice the level of Hiiu, Järva, Harju and Rapla counties.

Still, most counties saw slight improvements. The biggest drops came in Lääne-Viru, Saare and Võru. Harju County bucked the trend, with a one percentage point rise, including in Tallinn.

Behind the numbers: deprivation creeps into everyday life

While headline poverty rates tell one story, the experience of deprivation tells another.

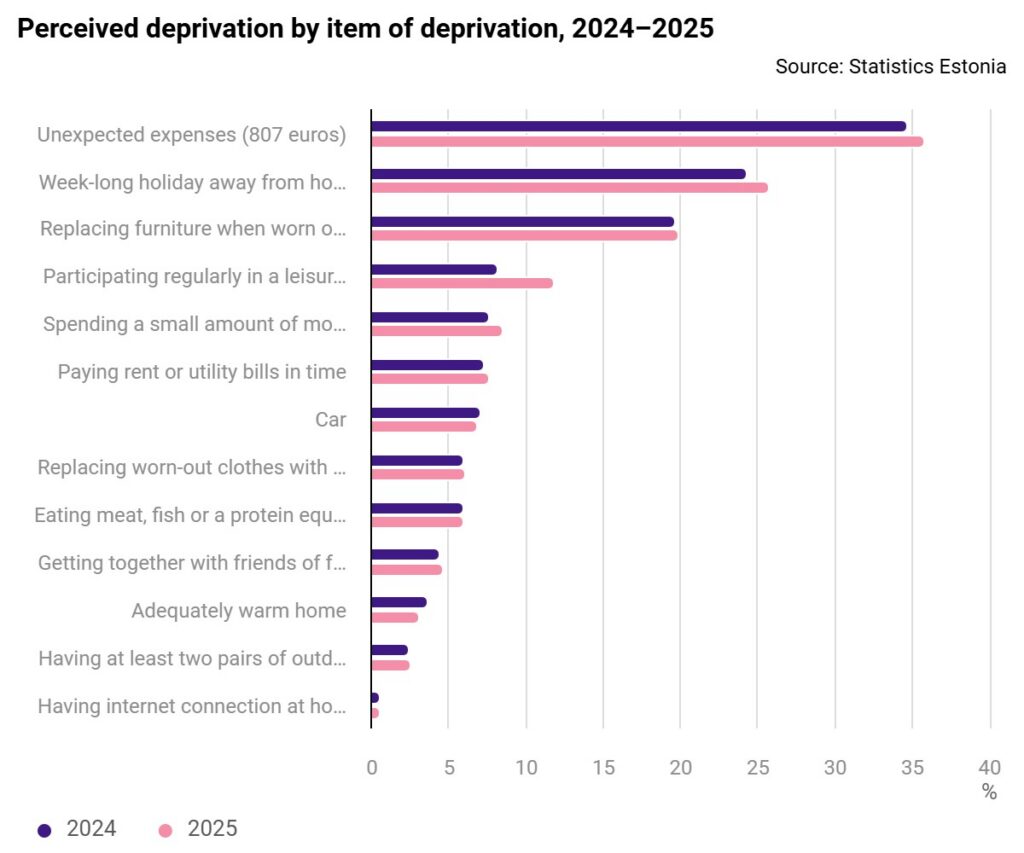

The share of people who say they cannot afford basic items – from adequate heating to a week’s holiday – remained steady at 7.7%, roughly 94,900 people. But the specifics of what people say they are forced to give up are shifting.

A growing number cannot afford paid leisure activities: one in eight people said regular hobbies were out of reach in 2025. One in five cannot replace worn-out furniture. One in four cannot afford a week away from home.

And more than one in three say they cannot cope with an unexpected €807 expense, a striking indicator of financial fragility beneath Estonia’s otherwise solid economic façade.

Lone parents again stand out: 19.1% experience deprivation. Among older people living alone the rate is 12% – improved, but still high.

Government: “We cannot slow down”

The Estonian social affairs ministry acknowledges the mixed picture and argues that Estonia must stay the course on social reforms.

“Our goal is for people in Estonia to live a dignified life,” said Kati Nõlvak, head of economic subsistence at the ministry. “The economic situation of elderly people living alone has improved significantly. But reducing poverty requires consistent effort.”

The ministry points to pension increases, nursing care reform – which has cut the share of care-home costs borne by families from 78% in 2022 to 52% in 2024 – and changes to child and parental benefits.

Nõlvak emphasised that while the share of household income coming from child benefits has fallen, the actual payments have not; rather, wages and pensions have grown faster. Reforms next year will allow parents sharing parental benefit to earn extra income without penalty, and the state plans to raise subsistence benefits once the new budget passes.

A widening divide

The overarching message is clear: Estonia is closing the poverty gap for older people, but risk is rising sharply for families – especially those raising children on their own.

With income inequality easing but absolute poverty deepening, the country is entering a new phase where the traditional markers of deprivation are being replaced by subtler ones: the inability to take a holiday, replace furniture, join a hobby, or face a surprise bill.

The survey, conducted with nearly 5,000 households as part of the EU’s harmonised SILC programme, captures not only Estonia’s progress but also its vulnerabilities.