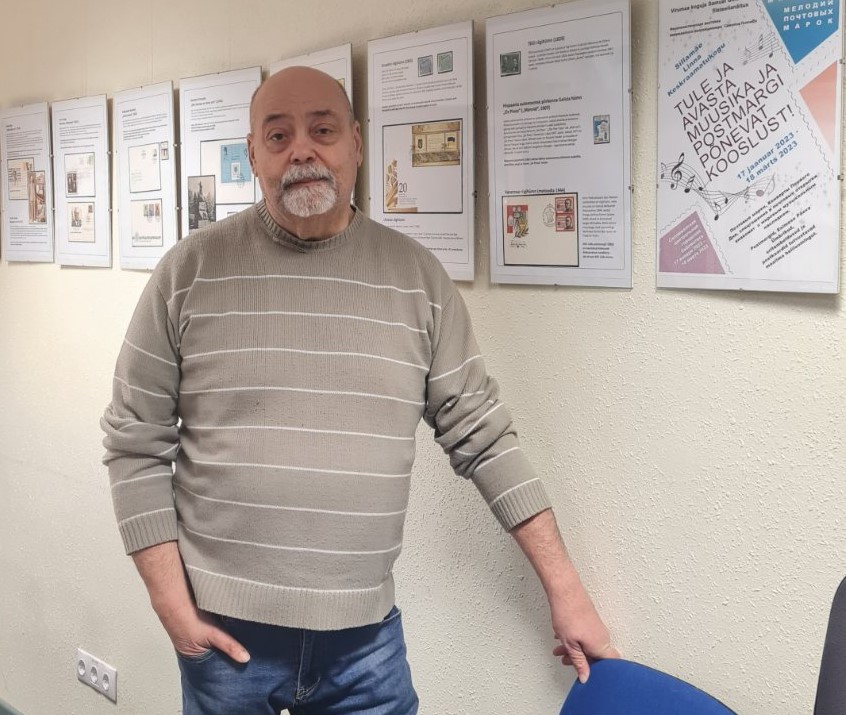

Educator, cultural advocate and lifelong philatelist Samuel Golomb wears his Jewish-Estonian identity with pride; from his childhood in Rakvere to championing integration in Ida-Virumaa, he has spent decades preserving memory, celebrating diversity and believing in the enduring strength of small nations.

With a diverse and inspiring background in education and culture, 68-year-old Samuel Golomb takes great pride in his Jewish-Estonian roots. A phrase often uttered by his mother – sometimes with a sting – “Because you’re a Jew!” has, in fact, helped him remain true to his goals and succeed in life.

When asked what it’s like to be Jewish in Estonia, how strongly he identifies as Jewish, and how important it is to him, Samuel says, “We all come from our childhood. I was always told never to be ashamed of my nationality. And if someone laughs at you for being a Jew, don’t let it get to you. Rise above it!”

By “rising above”, his mother and grandmother meant excelling through knowledge, skills and talent. “I wouldn’t go so far as to say I’m especially talented or better than others, but when a child is constantly told from an early age that they must be the best in class, the best in drama club – because Arkady Raikin is a Jew, Eino Baskin is a Jew, and you have to be just as good – that builds character,” Samuel reflects.

He says he feels very much at home in Estonia – perhaps even too much so – especially compared with many other minorities or members of the Jewish community. He attributes this comfort to the fact that he didn’t come here after the Second World War.

“My ancestors lived here during the Tsarist era. My grandmother was a true Estonian lady who called Pärnu ‘Pernau,’ Tallinn ‘Reval’ and Tartu ‘Yuryev’. Those are my roots. My mother worked for 43 years at the Mõdriku Technical School as a teacher of English, German and Russian. That’s why I consider myself an Estonian, who moreover speaks fluent Estonian. And that’s also why life here is good for me,” he explains, drawing a distinction between himself and members of the Narva Jewish community who arrived in Estonia post-war and know little of pre-war Narva or Estonia.

Jewish at home, Estonian in spirit

Whether you’re Jewish or not, you can’t be locked into your ethnicity alone, Samuel believes. “I was born on an interesting day – 17 January. My mother always said it was a godsend that I wasn’t born on 24 December. ‘How would we celebrate a birthday or a jubilee when Estonians are having a quiet Christmas Eve?’ she would ask.”

So, from childhood, Samuel understood that no matter how festive 24 December might be for him, he had to respect that the Estonian neighbours were lighting candles and observing a peaceful Christmas. “That’s the kind of spirit we lived in, in Rakvere. I’m a Rakvere boy.”

In his childhood home, all things Estonian were cherished. In addition to Jewish holidays, they celebrated all the Estonian ones too. Since 1985, Samuel hasn’t missed a single Song Festival. “You really need to understand what your country lives and breathes,” he says resolutely.

Today, he believes this cannot be said of many in Narva. Having lived in Ida-Virumaa for 17 years, he points to the lack of Estonian language skills – and indeed Estonian-mindedness –among locals as a major problem. “Even if you don’t speak Estonian, you can read about Estonia in Russian. And if you want to go to the Song Festival, you don’t need to speak Estonian – you can just go to feel and breathe with the crowd.”

Samuel shares the example of a young man from Narva who’s been his driver for the past year and a half. “We often talk about life and even argue. It’s one thing not to know where Toila Park is – fine. But not knowing where [the Estonian towns of] Paide and Türi are? That’s a serious gap. He’s lived in Narva all his life, never travelled anywhere, listens to Russian radio, watches Russian TV and lives in his own bubble. I’ve told him about the ‘Creative Cauldron of National Cultures’ festival, about the Narva cultural societies. The Russian cultural association Nadezhda alone has 1,200 members – an enormous number for one organisation. They sing and dance, have their own libraries, national costumes, exhibitions and projects. He looks at me with wide eyes. He has no clue.”

An ageing community with few young members

When news broke in February that the Tallinn Jewish kindergarten would be shut down, Samuel saw it as a sign of two trends: a lack of funding and an ageing community. “There are hardly any people in their 40s or 50s anymore – so no children either. The people who ran the kindergarten and private school were dedicated, but unfortunately the Jewish community couldn’t afford to maintain both institutions.” (The private school was also closed – ed.)

“They were bold in their ambitions – they organised summer camps, themed days, trips, stood on their heads to make it fun,” Samuel recalls. Fortunately, Jewish education is still available in Estonia at the primary and secondary levels.

The ageing community isn’t unique to Jews, Samuel adds. “Our Jewish community in Narva has 45 members – and at 68, I’m one of the youngest,” he says. “All the children have moved away. One of mine is in Finland, the other in Spain.” Even the roundtables for national minority cultural associations in Ida-Virumaa are attended mostly by elderly people, as are events like the Creative Cauldron festival. “That’s a clear sign – we’re not seeing a new generation coming up. Ethnic education in Estonia is in a tough spot,” he concludes.

Yet Samuel also finds pride and joy in recent positive developments – such as the memorial stone recently unveiled at the former site of Narva’s synagogue. “That was a major project – years of hard work. There were excavations, multiple visits to city officials, countless approvals,” he says enthusiastically. “Now we have a new project: the Narva Jewish cemetery, where the first person was buried in 1850 and the last in the 1940s.” The cemetery, now overgrown and swampy, is slated for drainage. “Right next door is the Tatar cemetery – we’re neighbours: Jews and Muslims!” he laughs. The plan is also to erect a small memorial there.

“In Rakvere, we also want to mark the site of the former synagogue on Rohuaia Street. We’ve restored the Jewish cemetery’s fence, cut down trees – there are 93 graves, some dating back to the 1700s. These projects matter, and they need someone to lead them,” he says with conviction.

A thriving community includes everyone

Despite the lack of young people, Samuel is heartened by the active Narva Jewish community. So too is the Ida-Virumaa Jewish community, led by Aleksandr Dusman, who was recently named an honorary citizen of Kohtla-Järve and received an award for promoting integration.

“Aleksandr Dusman has worked in Kohtla-Järve all his life and is also Jewish. He led the roundtable of national associations for many years.” (Now chaired by Maire Petrova – ed.) “I often joke that it took a Jewish chairman to keep 36 national associations in Ida-Virumaa working together at one table,” Samuel chuckles. He adds that while the Ida-Virumaa Jewish community is more academic in nature, the Narva community feels like one big family.

Samuel also maintains ties with the Jewish community in Kohtla-Järve. “There are about 40-50 of us. We meet once or twice a month for a discussion club. Topics range widely but are always Jewish-related. Someone gives a presentation, we discuss, and then we have tea or coffee together.” They also celebrate all Jewish holidays – from Rosh Hashanah and Passover to Hanukkah and Purim.

“Once a year, we go on an excursion I organise, called ‘Know Your Estonia’,” he says. The group has visited Lahemaa National Park, Tartu Botanical Garden, the AHHAA Centre in Tartu, Rakvere, Lake Peipus, Viljandi and more. “We take a bus, and people from Belarusian and Russian cultural associations join too. We pay for everything ourselves – no support. But because the group is committed, we go,” Samuel says, pleased with the multicultural cooperation in Narva.

Last year, the Ida-Virumaa Jewish community celebrated its 35th anniversary. “We published a commemorative book documenting key moments in the history of Narva’s Jews,” Samuel says proudly. The organisation has also translated into Russian two Holocaust-themed booklets by Samuel’s classmate, the Rakvere-based Christian pastor Stanislav Sirel, originally published in Estonian. “I translated them, and now people can read them in Russian too.”

At the end of our long conversation, Samuel states that no other ethnic association in Estonia looks after its elderly as generously as the Jewish communities do. “During the COVID pandemic, we received masks, disinfectants, and medicine,” he says. “We have a Maxima card programme where money is transferred so we can buy groceries. Part of our medication receipts and winter utilities are reimbursed. Our social programmes are strong. Hats off!”

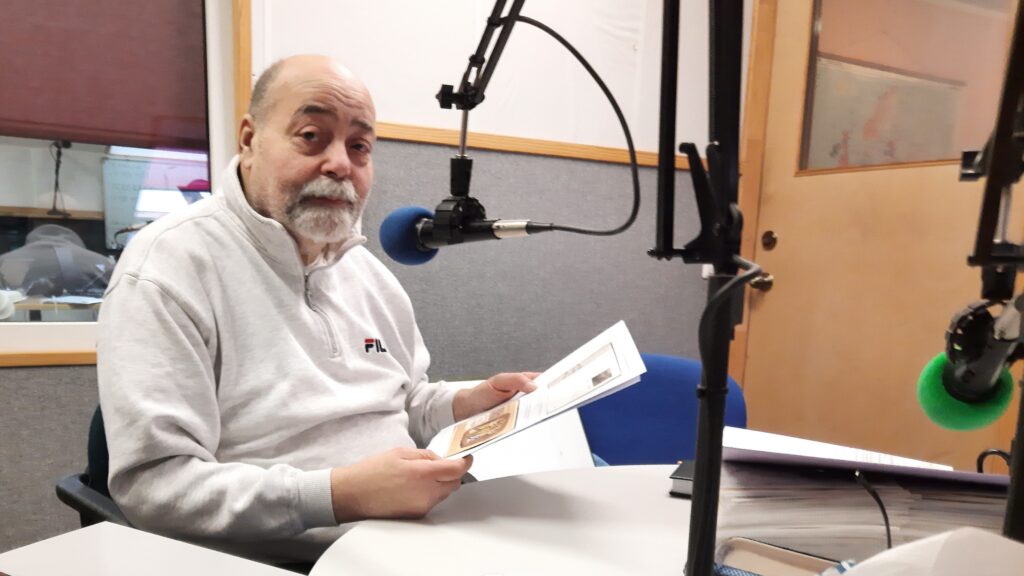

A lifelong passion for stamps

One of Samuel’s greatest hobbies since childhood has been stamp collecting – a passion first sparked when his mother gave him his first album for his eighth birthday. “Stamp collecting is a very Jewish hobby. In Israel, many people collect stamps. Actually, it’s not even a hobby – it’s an illness,” he jokes.

Thanks to his enthusiasm, Samuel now has pen pals from Argentina to Sri Lanka. A shared hobby makes it easier to connect and maintain friendships – even if political views differ sharply. He exchanges letters with a man in Russia, with whom he also shares personal thoughts. “We’ve discussed Putin’s war: he says his country is in the right, whereas I call it a fascist state,” Samuel explains. Despite the differences, there’s still a human connection.

He continues to grow his collection thanks to this global network. “As a pensioner, I don’t have the savings to buy lots of new stamps. I do buy some – but mostly cheap ones. I get new stamps through blind exchange. I post an ad offering to trade 500 different stamps for another 500 from anywhere in the world.”

“It’s a surprise for both sides – you don’t know what you’ll receive,” he explains. Samuel has an entire room at home dedicated to stamps, with seven shipments currently waiting to be unpacked and sorted – each containing between 250 and 500 stamps.

He aims to collect stamps from countries outside our region – India, Sri Lanka, Argentina, the United Arab Emirates – because they often produce more unusual designs. Through his albums, he’s witnessed the collapse of empires. “I’ve got one album of Yugoslavia, and next to it, seven albums from the countries that emerged after its breakup,” he says. “Same with the USSR – I have a thick album of Soviet stamps, and next to it, nearly 18 albums from the countries that arose on its former territory.”

“I’m a fan of small nations!” Samuel declares. “I was waiting for the independent Estonian state. I used to listen to Voice of America radio (a US-funded radio station that broadcast uncensored news into Soviet-controlled territories, offering many Estonians a vital connection to the free world – ed.) with an antenna bent from wires and hidden behind the wardrobe. That’s how we sat at home, waiting for the white ship to arrive.”

No matter how tense the political situation, Samuel believes that small nations will survive. “What Russia fears most right now is disintegration into small nations. And it’s entirely possible – there are strong people in Tatarstan, in Dagestan, and plenty of freedom-minded folks. But Russia crushes them all.”

***

Two final questions

Favourite Jewish author?

Sholem Aleichem. My aunt had a collection of his works at home, so I read everything in Russian. Many don’t know that the famous musical Fiddler on the Roof is based on his story Tevye the Dairyman.

Favourite Jewish artist?

Marc Chagall. A few years ago, the Belarusian society Sjabro in Narva and our Jewish association ran a joint project for Chagall’s 135th birthday. There were quizzes, drawing contests, and other events. Through that, I learned more about him – and he really resonates with me.

The article is part of the media programme “Estonia with many faces,” which highlights the richness and diversity of Estonian culture. The programme is supported by the Estonian Ministry of Culture and co-financed by the European Union.