Under the current populist government, the human rights have started to deteriorate in Estonia – and everyone must ask whether they have done enough to stand up for those rights, writes Egert Rünne, the executive director of the Estonian Human Rights Centre.

The Estonian version of this article was published in ERR.

Everyone has human rights that must be protected by states and other people and this has been a key message of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights already for 72 years. The importance of the Universal Declaration as a defender of everyone’s human rights is the reason why Human Rights Day is celebrated annually on 10 December.

The protection of fundamental rights is not only for the fulfilment of international agreements, but the Republic of Estonia is also founded on the respecting principles. Already 102 years ago, when we founded the republic, we recognised that respect for and observance of fundamental rights would help create a just and a secure country.

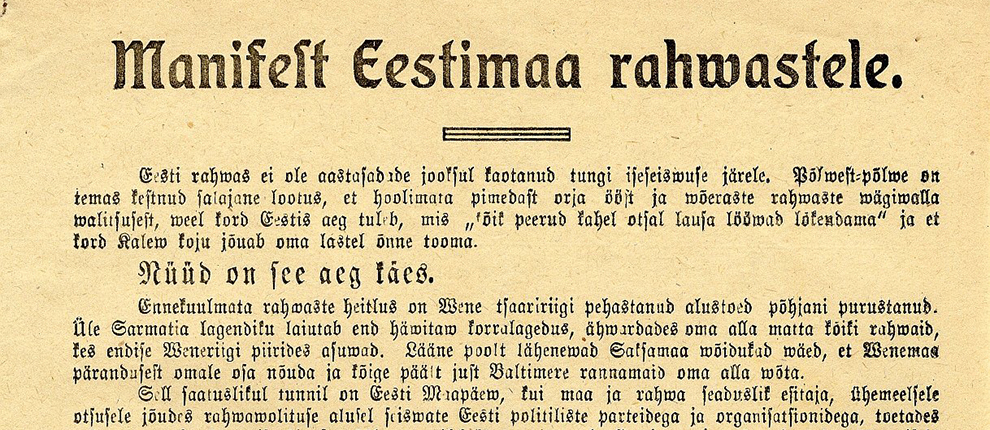

Equal treatment, the rights of national minorities and civil liberties were important in the 1918’s manifesto for all the peoples of Estonia. Thus, from the beginning of the republic, it has been a clear goal to create a democratic country governed by the rule of law in Estonia.

(Re-) establishing a democratic rule of law

Throughout history, our society has had times when many freedoms have been restricted. Fortunately, I have lived all my conscious life in Estonia that has respected and protected human rights. Until recently, the human rights situation in Estonia had improved by each year I have lived.

In the 1990s, the Estonian people were motivated to fight for democracy; we wanted to restore a state that respected our fundamental rights – and we succeeded. By the first decade of the 2000s, we had reached a basic level of human rights protection to gain access to the European Union’s club of value-based countries. In the second decade, the discussion focused on ensuring equal opportunities for women and various minorities.

In his recent book, “A Promised Land”, Barack Obama wrote that the goal of a democratic state must be to empower all people to stand up for their rights, not to suppress them.

In the last decade, Estonia started to get there. For example, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was ratified because everyone deserves equal treatment. The state also understood that asylum seekers must be treated more humanely – that they do not need to be hidden in the middle of the forest by the Russian border.

In addition, Riigikogu, Estonia’s parliament, passed the Cohabitation Act (a civil partnership bill, legally allowing the registration of same-sex partnership – editor) because every family needs protection. Estonia also participated in the redistribution of refugees during the European migrant crisis in 2015, understanding the concerns of other countries.

Of course, the situation was far from ideal even then; there were still many problems to be solved. But there was hope that things would get better little by little and, most importantly, there was will.

A lust for power at the expense of the protection of human rights

Before the last Riigikogu election in March 2019, the Human Rights Centre analysed the election programmes of all the political parties in the context of human rights.

The Estonian Centre Party (Keskerakond) had the most comprehensive programme protecting and promoting human rights. The party promised, for example, the introduction of a general ban on discrimination, clearer regulation on incitement to hatred, an increase in free legal aid (including in Russian), assistance to abused children and much more.

Those seeking power often have to decide what is the price of power and what to sacrifice for it. After the election, the Estonian Centre Party decided to form a coalition with two parties (The Estonian Conservative People’s Party or EKRE and Isamaa) whose election platforms either lacked or were even meant to cause a backlash on the human rights issues. As a result, a few human rights aspects reached the coalition agreement.

Moreover, as we see around us every day – despite its hopes, the Centre Party has not been able to change its coalition partners. Instead, its partners have given free rein to the backwards leap and blurring of constitutional ideals.

The fragility of human rights is not just an empty phrase

The coming to power of the new coalition was immediately accompanied by the dismantling or reversal of what had been achieved before. The decision was taken to end participation in resettlement and relocation programmes for people in need of international protection. Political pressure on journalists critical of the government, attacks on state institutions and civil society –especially minority and women’s rights organisations – increased.

Yes, you might think that in the first year it was just all talk and intimidation by the coalition politicians. Some in the society were voicing opinions that everybody should just be quiet and it would pass. It did not pass. On the contrary, the trend of deteriorating human rights in Estonia is becoming increasingly clear.

We have noticed this both in people’s appeals to the Human Rights Centre and while preparing various analyses – for example, in a recent report submitted to the UN. The report was prepared by interviewing several Estonian people about the human rights situation.

The pandemic opened the door to hasty legislative changes on migration issues and to casual suspension of the Convention on Human Rights. In addition, the extraordinary situation has not put an end to the authorities’ policy of bullying women, minorities and foreigners.

The intimidation and temporary suspension of several NGOs’ funding, bullying of foreign students, polarising the “marriage referendum” and support of anti-abortion groups are disturbing examples of the trend, the results of which can be seen in both Poland and Hungary. But the patterns are familiar from history.

Yes, these are small steps taken individually, but no society changes overnight – it is changed little by little, starting with the restriction of freedom of the most vulnerable.

Human rights are fragile and a rhetoric or a legal text on paper is not enough to protect them. In Estonia, which has reached a turning point in the protection of human rights, everyone must ask themselves whether they have done enough to stand up for the human rights of themselves and others.

Or have you given it up and adapted to a situation where the dream of Estonia that respects everyone’s human rights is becoming more and more distant and inaccessible. The situation is not hopeless yet. Yet.

The opinions in this article are those of the author. Cover: The Estonian prime minister, Jüri Ratas (sitting, on the left), chatting with the foreign minister, Urmas Reinsalu (sitting, on the right), while the culture minister, Tõnis Lukas (standing, on the left) shakes hands with the finance minister, Martin Helme, the leader of EKRE. The image is illustrative. Photo by Stenbock House.