On 31 August 1994, the last Soviet – or rather Russian, since the Soviet Union had ceased to exist three years earlier – troops finally marched out of Estonia. Their departure ended more than half a century of foreign military presence and completed the country’s long, often painful restoration of independence.

The pattern had begun in June 1940, when Soviet forces first occupied Estonia and stationed troops across its territory. Barely a year later, Nazi Germany swept in. For three years the swastika replaced the hammer and sickle, but in 1944 the Red Army returned and its presence would prove far more enduring. For the next fifty years Estonia was a Soviet garrison state, its land dotted with military sites, its coasts patrolled, its towns watched.

By the time Estonia restored independence in August 1991, its territory was still thick with foreign uniforms. On 21 August that year, the Soviet army controlled more than 570 sites, and some 35,000 personnel were serving on them. For a republic of barely 1.5 million people, the scale was overwhelming.

The slow start of negotiations

Talks on withdrawal began immediately after independence. At first the discussions were with the Soviet Union, but by December 1991 the Soviet state itself dissolved and the troops were re-badged as Russian. From April 1992, negotiations continued with representatives of the Russian Federation.

The process was never smooth. “In 1992, the Russian side offered 2002 as a possible deadline,” the Estonian foreign ministry later recalled. “As there was no way Estonia could agree to this, the meetings and consultations continued and the Russians finally promised to leave by 1997.”

But Estonia insisted on an earlier date. Its diplomats argued the Russian withdrawal should coincide with that from Germany, where the deadline was set at 31 August 1994. Backed by the United States, Sweden and a cluster of Western partners, Tallinn pressed its case in every forum available – the UN, the CSCE and the Council of Europe among them.

Enter Yeltsin – and the vodka

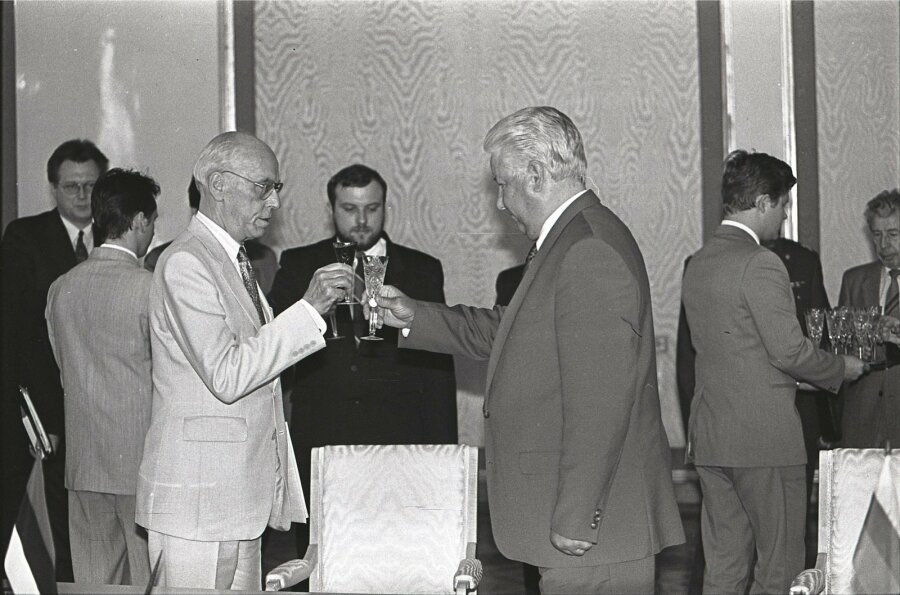

The breakthrough came in the summer of 1994. On 26 July that year, President Lennart Meri led the Estonian delegation to Moscow. Opposite him sat Boris Yeltsin, Russia’s ebullient and unpredictable leader. The initial reception was stiff; Russian officials showed no appetite for compromise.

But Yeltsin had little patience for his own bureaucrats. Having been told by US president Bill Clinton that Meri was “a stand-up guy who could get things done”, he took matters into his own hands – literally. Instead of letting the talks circle endlessly, he invited Meri to join him for vodka.

Meri, no heavy drinker, nonetheless obliged. From a long list Yeltsin offered, he picked Absolut – “so things would be absolute between us.” Yeltsin roared with approval and began drinking with gusto. Meri, ever the diplomat, quietly tipped his own shots into the soil of a nearby palm. The Russian president got merrier; the Estonian president stayed clear-headed.

Whether through spirits or spirit, the deadlock broke. That very day, Meri and Yeltsin signed a treaty setting the withdrawal of Russian troops from Estonian soil. The deadline: 31 August 1994.

The fine print – pensioners and Paldiski

The Moscow talks produced more than just a withdrawal agreement. A parallel treaty covered the rights and social guarantees of Russian military pensioners resident in Estonia. Another, signed on 30 July, dealt with the neutralisation of the nuclear training site at Paldiski on Estonia’s north-west coast. The base, once one of the most sensitive in the Soviet arsenal, would no longer be treated as a military installation.

The Russian troops departed as scheduled by 31 August 1994. On that day, Moscow submitted the agreed list of pensioners, and the Estonian government committee tasked with their oversight began work the very next morning. Paldiski itself was fully transferred to Estonia by 30 September 1995.

A turning point in foreign policy

The treaties did not pass without controversy. In Tallinn, opponents argued fiercely over the concessions made on the rights of Russian military pensioners. Yet despite looming elections, there was near-unanimity on the strategic direction: Estonia would pursue integration with the West while seeking a stable, if often difficult, relationship with its eastern neighbour.

The 1994 withdrawal was more than a military milestone. It was Estonia’s first major diplomatic success in concert with its Western allies, a test of the young state’s resolve and flexibility, and the moment the country shook off the last visible chains of occupation.

The palm tree in Yeltsin’s office may have been left a little worse for wear, but Estonia had reclaimed its soil – and set its course firmly towards NATO and the European Union.