Digital platform DigiAudit monitors indoor climate and energy use in schools and kindergartens.

This article is published in collaboration with Research in Estonia.

Clean air makes all the difference. Studies have shown that people learn and remember better in the fresh air. We also sleep better and get sick less often.

As most people spend much of their time indoors, it’s important to ensure the air doesn’t become toxic. It should be especially evident in educational spaces with children trying to learn; unfortunately, that’s not always the case.

Nearly half of the systems designed to keep the air ideal have issues. A US government study, conducted in 2020, showed that 41 per cent of schools need to renovate their heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems.

So how do we know what needs fixing?

A team of Tallinn University of Technology – also known as Taltech – researchers have developed a digital platform DigiAudit for that.

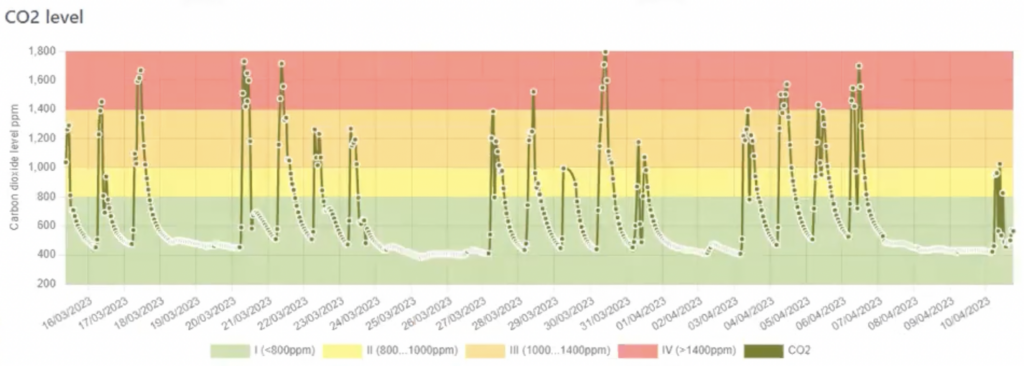

It monitors the temperature and CO2 concentration indoors in real-time. DigiAudit also analyses the use of heat and electricity in the buildings, ultimately enabling building managers to cut costs.

The researchers worked closely with local municipalities during a FinEst Centre for Smart Cities project, with 45 kindergartens and schools providing their data for the project.

“Modern and renovated non-residential buildings are already equipped with thousands of sensors and devices that are used to control heating, ventilation, and lighting,” explained Martin Thalfeldt, an assistant professor at Taltech’s Nearly Zero Energy Buildings Research Group and one of the creators of DigiAudit. “This means there is a lot of data hidden in buildings that are rarely used.”

DigiAudit collates all the information onto one platform to look for anomalies, patterns and issues in the building. This one-of-a-kind solution can also receive information from digital energy meters that collect electricity and heat usage information.

Almost all the buildings in Estonia have these smart meters, making it one of the first countries in the world where consumption data is automatically sent to the energy company throughout the entire country since 2016.

DigiAudit utilises this billing data.

The outcome is an overview of the building’s indoor environment quality and energy consumption. It becomes especially useful when the local government or building manager plans to or already has made changes, like installing solar panels for the first time or changing the ventilation system. Thalfeldt explained that the platform can visualise the impact of that change for you so that you can make more informed decisions in the future.

“DigiAudit enables us to optimise the costs,” Marek Treufeldt, a project coordinator in Estonia’s second-biggest town, Tartu, said. “Thanks to the energy consumption data, we can decide which building should be renovated next and where we can reduce expenditure the most.”

Estonia’s fascination with energy-efficient buildings

In Estonia, rain, snow and wind are the norm. People spend a lot of time indoors, a fact that is reflected in the statistics too. Buildings account for 53% of the total energy consumption in Estonia.

There is a lot of attention on the air quality and energy-efficient buildings in the country. TalTech has an innovative, nearly zero-waste building with a test facility where Thalfeldt and his team can simulate ventilation and heating in offices, schools and residential buildings.

Estonia has another advantage for air quality research. A study carried out a few years ago showed that Estonia is among the countries with the most energy-efficient new buildings in Europe.

Estonia implemented a law in 2009 that requires every new building to have minimum energy performance requirements, becoming one of the few European countries to do so.

Improving the quality of the buildings is not, of course, just an Estonian speciality.

The European Union has declared that it aims to be carbon neutral by 2050. Every member state has the freedom to approach it differently, but generally speaking, there shouldn’t be any buildings in the lowest energy efficiency class by 2030. As most Estonian buildings were built between the 1960s and 1990, there is a great deal of work ahead.

“Since there was a lot of cheap energy in the Soviet Union, energy efficiency wasn’t something leaders cared about,” explained Thalfeldt. Now, things have changed. If the Estonian government wants to achieve its carbon-neutral goals, all the buildings must be renovated.

Hence why solutions like DigiAudit will play an increasingly important role.