An eyewitness account of life in Estonia at the beginning of 50 years of Soviet occupation in June 1940 – Estonia’s darkest hour.

When World War Two broke out in September 1939, no-one could have imagined the horrific consequences it would have for Estonia and its people. At the start of the war, Estonia had declared itself neutral and for a period of time life went on as usual. The first people affected in Estonia by WWII were the Baltic Germans. They were an ethnic minority comprising 10% of the population who had lived in Estonia for centuries. They had deep-seated roots in Estonia but that swiftly changed as a result of the war.

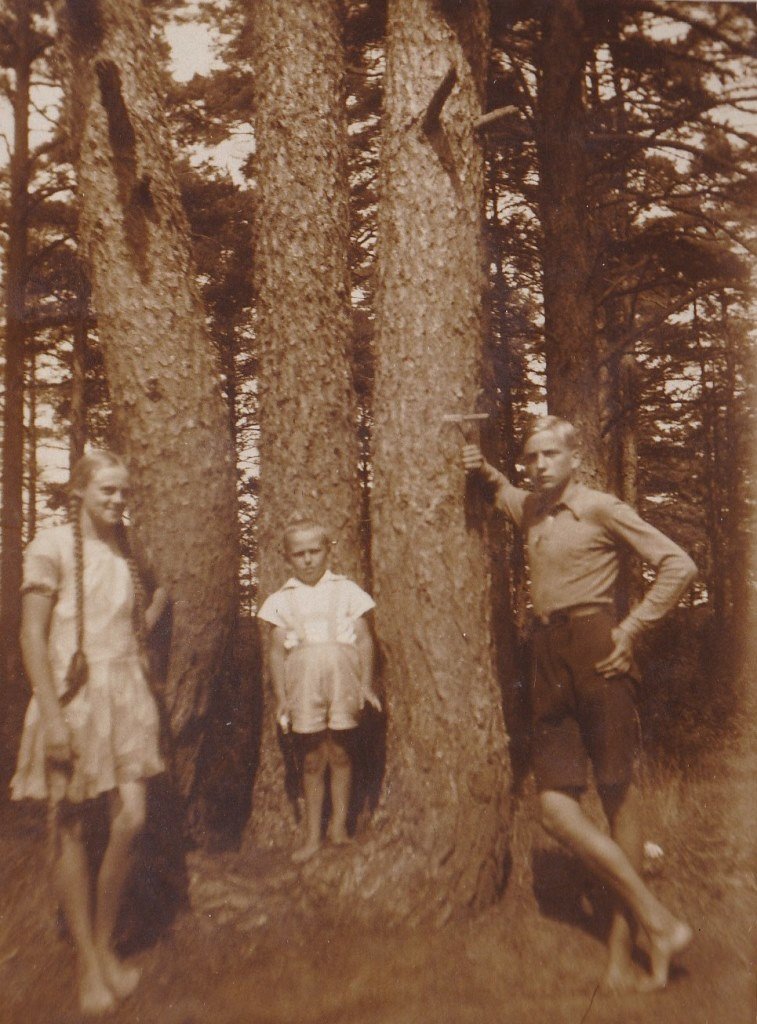

My grandfather’s cousin, Dorothea Niggul, was of mixed ethnic Estonian and Baltic German ancestry. News of the Baltic German resettlement programme came as a great shock, and although many Baltic Germans participated in the programme and left Estonia, many families chose to remain. Dorothea’s father was a patriotic Estonian who had fought in the Estonian War of Independence and later became a military judge based in Tallinn. As the Soviets tightened their grip on Estonia, her father’s life became increasingly endangered like so many others in government positions. Dorothea was sixteen years old when she and her family fled Estonia in 1941. Her memoir provides an insight into what people experienced in Estonia during those terrifying days.

Missed chance with Baltic German resettlement

September in the Baltic region was mostly a very beautiful month – the days were still bright and often sunny and the nights were already cool. Apples ripened on trees in all the gardens everywhere and their aromatic fragrance permeated the air everywhere you went.

School began again in September after a three month break which most town families spent in the countryside. And if one missed the rather free life from the summer holiday, one would also be glad to back in the city and at school again. There were, of course, lots of school friends and the coming winter also brought with it a welcome change.

Our family lived in Köie Street in Tallinn, a district only a few minutes’ walk from the Baltic Sea. The harbour was not far from our home and we often heard the horns and sirens of the incoming and outgoing ships. Our imaginations ran wild as we wondered where these ships came from and where they were going.

September in 1939 began just like any other autumn. We had certainly heard that Germany had declared war on Poland and subsequently invaded but the consequences of these events had not really affected anything in the comparatively remote Baltic region. However, suddenly we were also affected.

One morning at the end of that September my mother came into my bedroom clutching a newspaper in her hand. She said to me nervously that all Germans in the Baltic countries would be resettled to Germany. She said events were just beginning that would have far-reaching consequences but I couldn’t really imagine it.

My father, at that time, was in Kuressaare on the island of Saaremaa. He was a district judge in Tallinn who was required to travel to Kuressaare a few times a year to work through cases in the civil court. Dad was only too happy to make these trips – he loved the island of Saaremaa due to its unspoiled countryside and its somewhat rugged beauty which was typical of Estonia.

Dad was away on one of these trips to Kuressaare as news of the resettlement came. Since speaking to each other by telephone was nothing like as easy as it is today, my parents weren’t able to speak for several days to discuss what our family should do. We qualified to take part in the resettlement program due to our Baltic German ancestry but my father later convinced my mother that we should stay. When the time came to say goodbye to our German friends there were many hugs and tears and all of the German schools and churches were closed down. After the resettlement concluded it became apparent that many Baltic German families chose to remain in Estonia and life briefly returned to normal.

Grim reality brought by the Soviet occupation

The winter and spring of 1939/1940 passed. Most families went to the countryside during the summer holidays, among them my friend, Ined Pfaff, with her family. We later met up and travelled back to Tallinn by bus in the evening and laughed and bantered as we always did when we were with each other. In the bus sat an Estonian sailor who had been observing us closely. All of a sudden he said we ought to be happy and laugh while we still could because soon there will be nothing left to laugh about. The Russians were at the border and ready to invade Estonia.

There was nothing but disbelief from our side – why would they do this? Only John Anrich, who was somewhat older than us, seemed to pay attention and we saw that he looked really shocked. He began to ask the sailor about every last detail. We arrived home to find our parents extremely nervous. They sat by the radio listening for any new developments. It was first believed that Russian troops would not invade the entire country, but rather occupy key individual bases.

The Estonian government was toppled and a new government was installed consisting of hard-line communists who had been waiting for their chance for a long time. I still remember how the names of the new government ministers were read out on the radio in what seemed like an endless drone. At first, one was somewhat relieved that it was still an “Estonian” government but it was nothing more than a puppet regime.

After the bases had been occupied in strategically important areas, the Red Army now occupied the entire country as they did Latvia and Lithuania. The three small Baltic countries which had been established at the end of the First World War in 1918 after fighting tooth and nail for their independence had practically no chance of defending themselves against their enormous neighbour Russia. The Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians simply looked on in utter dismay as their own countries were bulldozed to rubble.

Grim days followed the Russian invasion of June 1940. The remaining Baltic Germans, my parents included, were completely shocked and bitterly regretted not leaving the country when they had had the chance. Even in the first days after the occupation groups of people streamed through the streets crying and chanting – unsavoury looking types, unkempt and in torn clothing. They were apparently meant to represent the “proletariat” which had never really existed in Estonia. Where had these people been pulled from? They were demonstrating that the so-called Big Brother, the Soviet Union had liberated them from their misery and were welcoming the occupiers. Virtually none of these individuals were in fact Estonians.

Mother and I were in town one day and happened to be surprised by a demonstration of this nature. We tried to get home via side streets, even when we got home I couldn’t be free of the shock. It was my father who suffered the most, he had been the driving force behind our family’s decision to remain in Estonia and he now had to carry this responsibility with him.

He often said in the years that followed that these had been the worst days of his life. He himself was in grave danger because he was a judge for the independent Republic of Estonia. He went into town often trying to gather as much news as possible. Coincidentally he was present when the Estonian flag was lowered from the Pikk Hermann tower and replaced with a Soviet flag. This was a ghastly sight for Estonians to behold and they could only look on in desperation.

After a period of time my father lost his job as a judge and the senior government official roles were replaced with hard-line communists. He was able to continue work for a period of time but soon had a young communist as a boss who made his life very difficult and frankly wanted to get rid of him.

Russian women taken aback by the glamour and wealth of Estonia

More and more Russian military had come to Tallinn in the meantime. Many officers and soldiers brought their families with them. These families were housed with Estonians and Baltic Germans. Whoever had a large home was forced to give up several rooms or even leave their homes. We did not have any Russians come to live with us but uncle Paul had to accommodate Russians in his home.

The Russian women were mostly friendly and well-meaning and couldn’t do much about their situation either. They mostly got on well with the women who had to take them in. Their transfer to the Baltic countries opened up a whole new world for them. It is now almost unimaginable how people lived during the Stalin era but it is a fact that women had nothing to wear which we in the West take for granted.

Many had no idea what underwear or garters were. They looked at shop display windows in complete astonishment as they marvelled at things such as night dresses and ball gowns, and of course this immediately made them want to dress like the ladies in Tallinn. The Estonian women accompanied these Russians to the dressmakers, advised them about which underwear to buy and it was actually a pleasant experience for everyone concerned; a small glimmer of humanity during an utterly inhuman time.

Escaping just in time

The various German families who chose to remain in Estonia were now desperate to leave. Again and again they discussed the possibility of a second resettlement to Germany. There was a German diplomatic mission in Tallinn but all enquiries were met with an icy rejection. They were told “You had your chance” and “the last ships left practically empty”. After much persistence and a petition, people’s prayers were answered and a second resettlement was approved. We didn’t waste any time submitting our papers.

Since it was summer our parents decided to travel once again to the countryside, to our beloved Anija. We were introduced to Anija a few years before by my father’s colleague, Judge Laanekõrb. He had likewise spent his holidays here with his family. I remember very well how he liked to walk along the river in his long white summer trousers.

Since it was summer our parents decided to travel once again to the countryside, to our beloved Anija. We were introduced to Anija a few years before by my father’s colleague, Judge Laanekõrb. He had likewise spent his holidays here with his family. I remember very well how he liked to walk along the river in his long white summer trousers.

In the summer of 1940 he was also there. One day a police officer came from Kehra, The policeman had known Judge Laanekõrb for years and told him it pained him to do this, but he had to take him in. Judge Laanekõrb did not take it seriously at all thinking it was simply a misunderstanding and that he would soon be back. So off he went in his white summer suit and we never saw him again. We learned many years later that he had been deported to Siberia where he presumably perished.

We heard again and again of deportations in Tallinn – people simply disappeared without a trace. There were some who returned after many years of exile but most were sick and completely broken, like our cousin Ralf who was deported not long after the second resettlement had taken place. Our father was also in very grave danger because of his profession. My parents, in fact all of us, knew of the danger and my parents had put together a precise escape plan should anyone come for us.

It was no longer pleasant in school, some teachers had been replaced, most were frightened to death and there were those who were aggressive and provocative – the wonderful mood of our past school years had completely disappeared. It was now expected that education should be carried out in the spirit of communism. The autumn of that year is very grey and dark in my memory, the atmosphere in our beautiful city had completely changed and everything felt so very repressive. People felt threatened by spies and uncertainty about the future was a very heavy burden to bear.

Months of tension and anxiety eventually came to an end for us when the competent authorities approved our resettlement. We were now free to go. It was now just a question of completing the last preparations as quickly as possible.

Our household was dismantled bit by bit. A few items were sold but most were simply given away. Our neighbours who lived above us, the Talivees, got a few things as well. Mr Talivee was an Estonian police officer who very kindly accompanied us to the port on the day of our departure. When I returned to Tallinn in 1978, I was very sad to learn that his family was also not spared the brutality of the Soviet occupation. In 1941, Mr Talivee was arrested and sent to Sevurallag in Siberia. He was originally given a ten-year sentence but that later changed and, in 1942, he was executed.

Mrs Talivee also came very close to being deported but one night, out of the blue, a soldier appeared at her door warning her that her name was on the list. Naturally she was extremely frightened by his words but she heeded his advice and went away for a few days. Before the soldier left he wanted to point out that he was not Russian, but Ukrainian. Perhaps this gesture was his way of doing something good in the evil world in which he found himself.

We left Tallinn on 17 February 1941 on board the second ship, “The Brake”. Taking any money out of Estonia was strictly forbidden. It was not until we had left Russian occupied soil and found ourselves in German territory that everyone felt a great sense of relief. We were finally safe! We later discovered, shortly after we left that Soviet soldiers had come thumping on our door to take father away. We had managed to escape just in time! We eventually got used to life in Germany but our hearts never really left Estonia.

I

Cover: Karl, Dorothea, Ellinor, Karl, and Alex in 1939.

Thanks for this essay Tania Lestal. It’s good and important to remember our history. This is how we can understand ourselves better. The hardships endured by our ancestors will not be forgotten. All these stories that are shared help us feel that we are part of an ongoing saga.

What a fantastically moving story. Thank you so much for sharing it with everyone Tania.

Wow what a great story. My grandmother fled Narva on a train just before the soviet invasion. She first went to Germany, then UK and finally! Canada. I am the first person in my family to move back to Estonia this year 🙂