Rein Raud has published eight novels and three collections of stories; three of his novels have been published in the Anglophone world. Estonian World asked him to share his experience with reaching out to the English-speaking market.

Estonians have become a reading nation, but it becomes more and more clear that Estonians also write a lot. With novel competitions getting plenty of submissions it seems there is no need to worry about the next generation of authors. The Tänapäev publishing house annual young adult novel competition got 30 manuscript submissions; although the number may feel modest considering the population, it’s an impressive achievement.

A small nation writing to each other with so many promising novelists and fiction writers, will there be enough possibilities to find readers? It’s only natural that an author would like to have their work read by as many as possible. Also, despite the deeply rooted image of a starving artist creating the immortal prose while freezing in a tiny basement apartment (penthouses have become fashionable and therefore out of reach for most aspiring authors), there is no shame in wanting to get paid. With many people speaking and writing good English, all the possibilities of an international market seem in an easy reach. From self-publishing to submitting manuscripts to publishing houses abroad, there are a lot of opportunities, but obviously the competition is also international.

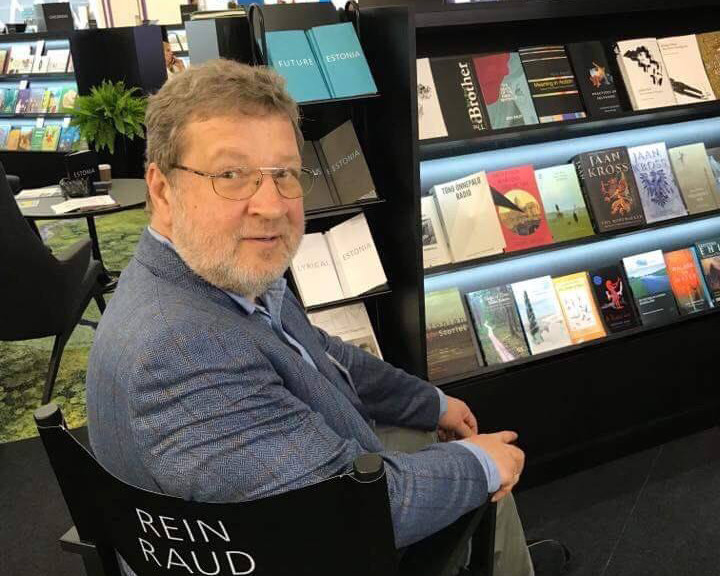

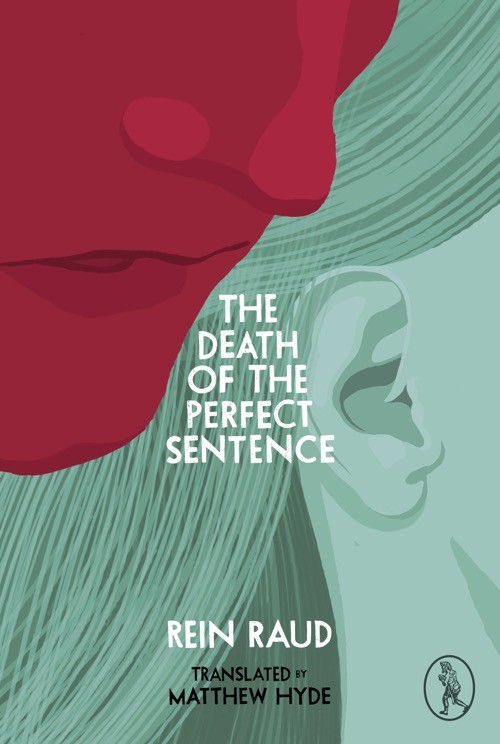

Estonian World asked an established Estonian author, Rein Raud, to share his experience with reaching out to the English-speaking market. Through his decades as a writer, Raud has published eight novels, three collections of stories and a number of translated works in Estonia. Three of his novels have been translated and published by publishing houses in the UK and the US, the latest being his “The Death of the Perfect Sentence” in 2017 by Vagabond Voices. He was also one of the authors asked to represent Estonia at the London Book Fair 2018.

Tricks of the trade – the practical side of getting your book published in the UK and the US

You have selected traditional publishing over self-publishing that has become so popular lately. Why?

Unless you are already really good at something, better leave the practical side of things to professionals. All of my publishers in the Anglophone world have dedicated readerships who follow their production, so their choice of my work is already an endorsement in their readers’ eyes, which even a good marketing campaign would not necessarily match.

Do you use a literary agent? If so, how did you find yours? Through the Estonian publishing world, searched yourself through cold contacts or networking on literary festivals, friends recommendations?

The Estonian Literature Centre has been doing a wonderful job in representing Estonian authors at events worldwide and bringing international publishers to Estonia to meet the authors. It seems Estonian authors aspiring for international success should perhaps concentrate on the quality of their writing in the first place.

You speak many languages, why did you choose not to make your own translations? How do you find the translator?

Well, on the one hand, my plate is quite full already, but even so I don’t have the confidence of a literarily gifted native speaker for all the stylistic nuances and registers. Just speaking a language, or even being able to write academic text in it (as I do in English) is not enough for literary translation of sufficient quality.

I do proofread many of my translations though, and I have a rule that I do not correct sentences that do not feel right to me, regardless of whether the translator has followed the original verbatim or not. Obvious mistakes stick out, of course – luckily, there are never so many of them – and sometimes there are stylistic choices I would definitely not have made myself. So if somebody wants to translate me from English, they are welcome to, because the text has been verified by me.

Marketing and networking your own book

How are the sales of your books going? If it’s not too personal, did you sign up for a flat fee or a sales-based contract and why?

The conditions of contracts differ and are based on the standards of the publishing houses. None of my books is a huge bestseller, but I hear “The Death of the Perfect Sentence” has entered its second printing. I also have received quite a few favourable reviews for all three books and I’ve been selected by some independent bookstores for promotion, which also helps.

You participated in the 2018 London Book Fair. How did it go and was it what you expected? How many business cards did you bring, how many did you hand out? Did you get a writer’s cramp from signing your books? Has anything solid come out of that experience or is it too early?

Oh, I didn’t count my business cards and I certainly didn’t expect them to immediately produce great publishing deals. There was a lot of interest though, in all Baltic authors, and quite a few of the discussions started during that fair have continued since.

A writer-in-residency – have you done it? Do you find it useful for concentration, networking and/or resume boosting or is it just a fashion thing?

Yes, I wrote the bulk of “The Reconstruction” during a wonderful month in Italy, a small town near Rome, in a spacious apartment and a nice balcony, and almost forgetting the sound of my own voice during the process, as there were sometimes days on end without anyone around to talk to. As to writers’ houses with lots of people working there at the same time – I’ve been to some a few years back, and written a bit, too, but I normally need solitude for my work. Luckily, for the last seven years I’ve had a country home and most of my writing is done there.

What networking methods do you recommend for an aspiring author? You are quite active on Twitter. What other self-marketing have you found most effective?

Well, my presence in the social media probably contributes toward the sales of my books a bit, but I am not on Facebook and Twitter for the purposes of marketing, even if I sometimes post about my books, lectures or readings. I have given interviews to all kinds of media outlets, including independent book bloggers in the UK and the US, but this is also not something I actively seek.

You have a personal website, do you manage it yourself? What benefits do you feel you get from it?

Yes, that is something I indeed do myself, but it is not so much trouble. I suppose the site comes up in Google searches among the first items, if someone has decided to look me up, so I have gathered a lot of information and links about myself in one place. About whether it is useful or not – I really can’t tell. But it is surely better to have it than not.

Bits and bobs

Bits and bobs

Is it plausible to make your living as a full time author?

No. There are very few authors in the world who write literature of high quality and also have such sales figures that they can live comfortably off it. Most of them come from big language areas and have the power of a strong establishment behind them. Children’s literature is an exception though, as parents still often prefer to buy good books for their children even if they don’t read much of these themselves.

Is it better to aim to be a big fish in a small pond or small fish in the ocean? Do you think it’s important that Estonian authors should try to get published abroad? There are writers who write in English already saying that the Estonian market is just too small.

If considerations of market size, income and fame are primary in the motivation of an author, my advice to such a person would be to do something else. I write in Estonian because this is my language, and this is where I am from. This does not mean there is a distinct “Estonianness” to my writing, or that anyone’s literature inevitably bears a stamp of their pedigree. I hope my books are interesting to their readers because they manage to touch something more broadly human than just the local sentiment, and yet the topics and characters of my work come from the life I know, or the past that continues to haunt it.

But I do also feel the fish pond effect. Let’s say, if there is one person in a thousand who likes to read the kind of literature I am trying to write, then there would be about a thousand of such people around in Estonia, and maybe not all of them would find their way to my book. In neighbouring Finland, for example, the population is five times bigger than ours, but the number of members in their Writers’ Union is just about twice the amount of ours, even though in Finland you are offered membership of the union automatically after you have published two books, while in Estonia there is a more complicated procedure and there are quite a few authors who have published a lot, but do not belong to the union. Our literature is thus quite big, considering the number of its readers. On the one hand, this suggests, of course, that our literature is thriving, but on the other, this also means it is much more difficult for our authors to achieve a stable readership.

In your interview on the turbulent times of 1992 you mentioned that the US was far more aggressive and dangerous in a sense of cultural takeover than Russia ever was. Two of your books are published in the US. Is that your attempt to bring culture to the US? Do you feel that, over the last 26 years, the cultural craving of Estonians have developed beyond hamburgers?

To the last question: yes, luckily. It should be stressed that I was talking about the cultural, not the political situation. We unfortunately still have to fear a lot from the side of Russia, especially now that it has reverted to autocracy, but for the same reason the likelihood that the Russian popular culture would outweigh Western influences in our world is close to zero. However, the pressure on Estonian literature has remained. Books in English are cheaper and most Estonians freely read English, some even speak their mother tongue with a large percentage of English words and expressions, sometimes so that only the grammar is what remains Estonian, with its case endings and tenses. So the fate of our culture is, for the first time in centuries, entirely in our own hands.

I have no tolerance for nationalism in the sense of thinking one’s own ethnic heritage is somehow superior than anyone else’s, but I do think our language should survive, and nothing but writing things in it that will really speak to others – including foreigners who might want to learn our language – can preserve it. Luckily, there is also the Estonian Cultural Endowment, a foundation to which a certain part of taxes on alcohol, tobacco and gambling are diverted and the funds are then distributed, not by state officials but artistic professionals, to projects fostering different parts of Estonian culture, literature included. If the cowboy capitalism of the early 1990s would have become the foundation of the Estonian cultural politics for a longer time, the Estonian literature would probably already be on its way to extinction, as the competition with imported works would be much more severe.

As to the US and the Anglophone world in general, I am very glad that the interest toward translated literature has risen significantly over the last decades and started to include also literatures in smaller and less known languages such as ours. All things considered, Estonian authors are doing quite well in the international market. Of course there is no need to “bring culture” to the English-speaking readers of literature, but to broaden the scope –well, maybe.

I

Cover: Rein Raud has published eight novels and three collections of stories; three of his novels have been published in the Anglophone world.