Estonians fleeing the aftermath of the Second World War and the Soviet occupation found their voice in Australia via a newspaper that continues to this day; Silvi Vann-Wall reports on Meie Kodu (Our Home) and the community it continues to serve.*

In the tumultuous time after the Second World War, and throughout the Soviet occupation of their tiny country, thousands of Estonians sought refuge in Australia – which for them held the promise of being as far away from the conflict zone as possible.

As war refugees, Estonians were required to live in migrant camps such as those in Bathurst or Bonegilla, before being given jobs and the chance at integration into the Australian society.

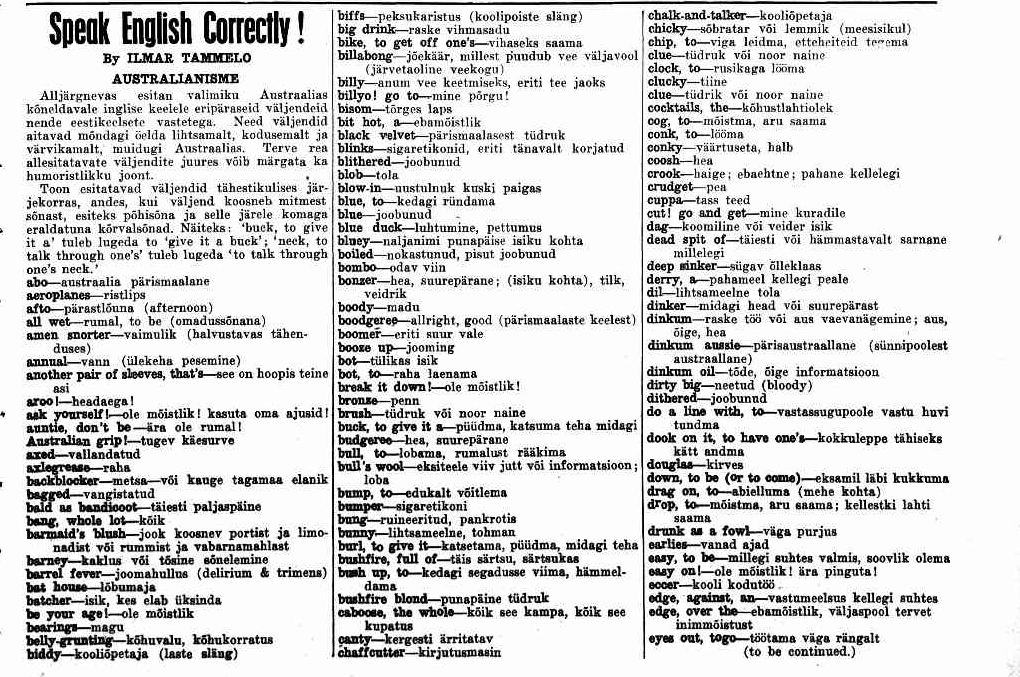

Meanwhile, a small committee, formed by the Sydney Estonian Society, was hard at work acquiring authorisation to publish the first Estonian newspaper in Australia, Meie Kodu.

Bringing comfort to refugees in a strange land

Literally translated as “Our Home”, Meie Kodu was a fitting title for a paper that hoped to bring comfort to refugees in a strange land. It would be published in the Estonian language only and bring news of the latest developments in Europe as well as of happenings in Australia. Although small, it was to become a key part of easing the transition between the European and Australian life.

The Sydney Estonian Society in 1949 decided that such a newspaper was sorely needed. So, in February of that year they called a meeting, led by chairman Toomas Varik, to request formal permission of the Australian government for this paper to be produced. It was also decided that chairman Varik would be the paper’s publisher.

Six months later, authorisation was granted on the basis that such a paper would make a major contribution to Estonian culture. But there was one condition: at least 25 per cent of the newspaper had to be in English.

Undeterred by this proviso, the Sydney Estonian Society soon formed a small news team, led by founder Ilmar Raudma. The team – all volunteers – got down to work straightaway, transcribing articles letter by letter on to a printing press, and printing photos from special plates – often working all night.

Advertisements on where to find Estonian delicacies

The first issue was published on 19 August in 1949, and more than 300 copies were printed. Volunteer packers and transport providers ensured rapid distribution throughout the Australian-Estonian community.

The first issue’s English section contained an introduction to the paper’s mission, an appreciation of press freedom (written by Raudma) and an impassioned article on “Soviet slavery”, republished from a volume of the newsletter “From Behind the Iron Curtain”.

The remainder, published in Estonian, was a mix of local and international news, political cartoons, a sport section and, most important, advertisements on where to find Estonian delicacies.

An emotional reaction

Thanks to their efforts, copies of Meie Kodu soon made their way to the migration camps, sparking an understandably emotional reaction for many detained there. “Really, so far from home and [we have] our own newspaper!” Ülle Slamer wrote in her “History of the Newspaper Meie Kodu” (quotes from which have been translated from Estonian).

Editor-in-chief Raudma was presumably well-versed in the constraints of a compromised and state-controlled press, having worked previously as an officer in the information department of Estonia’s National Propaganda Office. He managed to escape the Soviet occupation by way of Germany in 1944 and went to the US shortly thereafter.

Raudma had arrived in Australia only a year before the founding of Meie Kodu. It was no doubt a relief to be overseeing a newspaper in a country where press freedom was significantly greater than in the Soviet Union – where articles were heavily censored.

Raudma wrote in his first Meie Kodu article, “Our Appreciation”:

“We feel much obliged to the Authorities of the Commonwealth for the benevolent consideration of our sincere and firm desire to do all in our power to help the new settlers of Estonian nationality in this free and, in our opinion, happiest country in the world, to become a valuable addition to all good Australians. However, as far as the generations just arrived are concerned, we may become good Australians only by being, in the first instance, good Estonians.”

The fight for the Estonian liberation

Not content with the role of “detached watchdog”, the team behind Meie Kodu had an unabashed agenda: the liberation of the Estonian people. As Raudma’s colleague Juhan Viinang wrote in his introduction article, published in the same issue: “We propose to present the life of Estonians in Australia and elsewhere the Australian way of life, impartial information on international politics, Estonian cultural activity locally and abroad and to do our part in the fight for Estonian liberation and the combined struggle for the freedom of the world from the threat of Communism.”

So they pressed on, fighting systems of oppression the only way they knew how. Soon, Meie Kodu was circulating thousands of copies around Australia.

Unfortunately, Raudma died of leukaemia in 1951, leaving the role of editor-in-chief to Arnold Lond. In February 1954, the team was finally permitted to publish entirely in Estonian. This meant that newcomers struggling with the strange mechanics of English didn’t need to fret when reading their weekly news.

“The first decades of the newspaper were not easy,” Ülle Slamer wrote. Volunteers rarely had formal training, and the long nights spent resolving mechanical issues with the printing press were incredibly frustrating. The only pay they ever saw was a small reimbursement for the Sydney Harbour Bridge toll.

Keeping Estonia alive in the hearts of expats

It was often difficult to obtain information from the international scene, due to both technological and political constraints. “Not much news passed the Iron Curtain,” archivist Eili Annuk said. But Meie Kodu persisted and, contrary to what Wikipedia might declare, the paper did not cease production in 1955.

After all, they had a mission to “keep Estonia alive in the hearts of expats”, Reet Simmul, assistant archivist at the Estonian Archives in Australia, said. It’s thanks to these archives, established in 1952, that one can now access the first 50 years of the paper digitally.

From 1970 to 1992, Tiiu Kroll-Simmul was Meie Kodu’s longest running editor-in-chief. This period saw many changes to the paper, including better access to world news through evolving technology, and thus an ability to report in a more informed manner.

During this time, Annuk began to compile a written catalogue of every copy of the paper for the Estonian archives. In 1991, just near the end of Kroll-Simmul’s time as editor-in-chief, Estonians made world headlines by reclaiming their independence.

Estonia officially declared itself independent at a sitting of the Estonian Supreme Soviet on 20 August 1991. “We drove back from the Snowies [mountain range] to the newspaper office. Uino wanted the paper to publish the news immediately,” Reet Simmul recalled. (Uino Simmul, Reet’s husband, was the chairman of the Sydney Estonian Society at the time.)

Nearly half a century after that first issue, the original editors’ mission had been realised: Estonians were free.

Throughout the 1990s, Estonia’s press freedom improved dramatically, and the Estonian media were finally declared “free” according to the Press Freedom Index in 1993. That status has not only been retained ever since but this year it was ranked as the 12th freest in the world, beating out Australia at 19th.

Propelled into the modern age

With the gap between the Estonian press and their Western counterparts rapidly narrowing, Uino Simmul travelled from Sydney to New York in the ’90s, to see how its Estonian-community newspaper compared.

Inspired by the latest technology he saw there, Meie Kodu’s production was propelled into the modern age with the purchase of computers.

But, as the current editor, Aune Vetik, explained, production still involved plenty of manual work until 2004: volunteers did page layouts by the old cut-and-paste method, and the measuring tool “was an old rope”. Vetik, an Estonian national who first read Meie Kodu in 2004, assumed the editorship in 2011 and admits to being a little taken aback at how old-school the paper was.

“Everything in the office was very brownish-yellow and old, but still functional as it was 50 years ago,” she says. When she tried to shake things up and modernise the paper a bit, she was given an oft-repeated response: “We have always done it in this way.” Meie Kodu went digital in 2012.

A broader scope

According to Reet Simmul, going online and recruiting formally trained sub-editors improved the paper enormously: “The local articles [such as] reviews of amateur plays, church [and] coffee evenings at Estonian Houses have decreased,” she said, which has resulted in a broader scope of international politics and significant Estonian events.

Change has also occurred financially: the paper can now afford to pay its editorial staff. Thanks to such developments, (and Adobe InDesign), volunteers no longer have to slave over the unruly printing press, painstakingly shifting letters to the right position until the early hours of the morning.

Around Australia, absorption of Estonian communities into mainstream society is a cause of concern for all generations. The advent of an email subscription service is just one of the ways Meie Kodu hopes to resolve this issue.

After all, without the economic benefits gained from a lively Estonian-Australian community, the paper’s future is at risk. Publication costs are rising, and the news team is most often left to rely on public donations to bolster funding from Estonian committees. The print run, at only 220 subscribers, is consequently quite small.

The future is far from certain – but then that was the case in 1949 and in 1991 – and the paper, like the country that spawned it, has proven survival skills.

Cover: Copies of Meie Kodu being packed for delivery in 1950. Images courtesy of Silvi Vann-Wall. *Please note that Meie Kodu ceased operation in January 2019.