“Second Survey Shows Public Less Confident in Cabinet” was the recent headline on the news site of the Estonian Public Broadcasting (news.err.ee) and indeed, the numbers do show a worrying downward trend when it comes to trust in the Estonian government and parliament.

The numbers in question are those of Eurobarometer, an organisation that has existed in one form or another since the 1970s and whose purpose is to gauge public opinion on issues relating to the European Union and national governments. The latest bulletin from Eurobarometer gives us a chance to compare Estonian attitudes with those of the other EU member states in a way that is truly comparable.

To start with the bad news, it would seem that only 70 out of 100 Estonians are “satisfied” (either very or fairly) with the life they lead. It doesn’t seem that bad until you contrast it with the Benelux countries or Finland, who all rank well over 90. Even the UK, that nation of miserable whingers and moaners to which I belong, polled 91%.

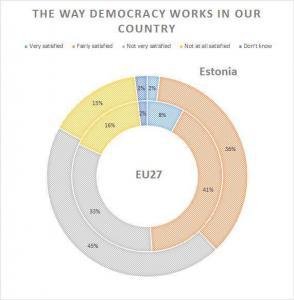

To continue on the theme that ERR has already written, democracy itself in Estonia doesn’t fair especially well either, with only 38% indicating satisfaction, against an EU average of 49%. Perhaps they should change the voting system?

Things pick up when it comes to “engagement”, with above average discussion of national, European and local political matters amongst groups of friends. Greece (perhaps unsurprisingly, considering its perilous state) took the award for “political interest”, with a whopping 40% saying they had a strong interest in politics against Estonia’s 14% (although the EU average is only 16%).

The economy is where you would expect reasonably good results and we are not disappointed – 38% rank “the situation of the national economy” to be at least good, which although not much compared with Sweden and Germany (75%) or Finland (55%), is double that of Lithuania (19%) and over double that of Latvia (17%). 35% in Estonia think the same of the European economy, which is somewhat on the high side, the average being a miserly 19%. The world economy is also thought of charitably, with 32% ranking it “good” versus the average or 23%.

Slightly disappointing was that 11% of Estonians didn’t know whether the European economy was either good or bad, against an EU average of 6%. Even worse was the state of the world economy, where 17% declared they didn’t know, 8% being the average. Could this be a reflection of the often joked about somewhat insular looking mind-set of the average Estonian? Answers in the comments section, please.

Rising prices (58%), the economic situation (37%) and unemployment (30%) were deemed the most important issues facing the country (NB – you could choose two categories from a selection). Lithuania was the only other nation where rising prices gained more than 40% (43% in this case) and the average is only 24%, so presumably this won’t go unnoticed in Toompea.

One oddity however is that 37% of Estonians (the highest percentage in the EU) said they didn’t know whether their personal job situation was good or bad. Compare this with 16% in Latvia, 19% in Finland and an average of 17%, this puzzled me rather. Usually people are aware of their job situation; they might not like it, but they know what it is.*

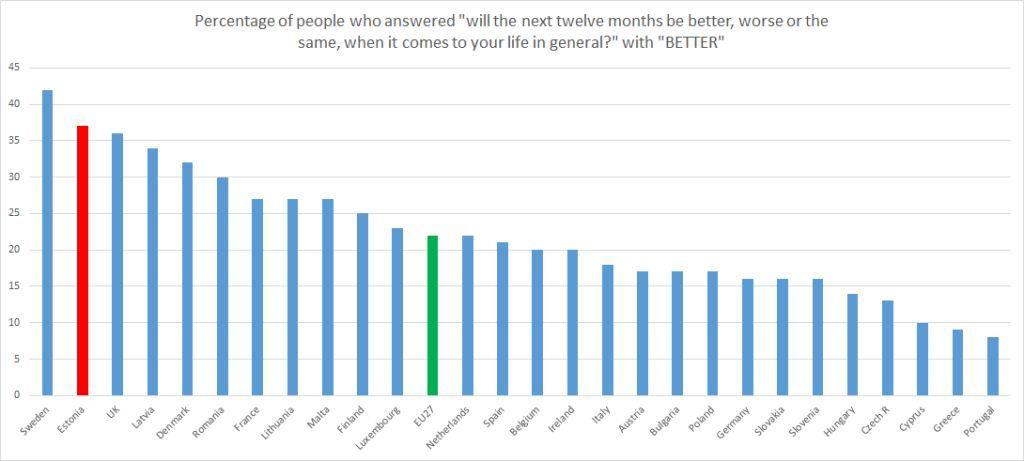

When it comes to the future, at least Estonians appear to be a more optimistic crowd. When asked “What are your expectations for the next twelve months: will they be better, worse or the same, when it comes to your life in general?”, 37% answered with better. When looked at in isolation, that statistic means precious little, but it is actually the second highest in Europe, trailing only Sweden (and one point above the UK). So whilst Estonians might like to gripe about the present, it seems they are, at heart, more forward-looking than we give them credit for. As Winston Churchill said about being an optimist, “it does not seem to be much use being anything else”.

*I asked an Estonian friend of mine why he thought this figure was so low. He says, “They really don’t know. On one hand they think they’re miserable, oppressed (by the government, their employer or whatnot), and on the other hand they’re happy that they have a job.” Now it does make sense.

I

The opinions in this article are those of the author.

Photo: VisitEstonia/Kaarel Mikkin.