Solaride, Estonia’s first entry to the Bridgestone World Solar Challenge in Australia, readies its solar vehicle for a high-stake international race, due to take place in 2023.

This article is published in collaboration with Research in Estonia.

The Bridgestone World Solar Challenge is one of the world’s most preeminent competitions for innovative solar-power vehicles. Held in Australia every two years since 1987, it welcomes entries from international teams spanning the globe, which then compete on a course across 3,000 kilometres (1,864 miles) of Outback, from Darwin in the north to Adelaide in the south.

Solaride, Estonia’s first entry to the challenge, was supposed to compete in the race this summer, but travel restrictions have forced organisers to delay the event until summer 2023. However, that bought Estonia’s all-volunteer team time not only to build a first-generation vehicle, but to consider the development of a second-generation car for the 2023 race.

Fundraising activities also continue, with the aim of not only developing a competitive solar-powered vehicle, but to develop Estonia’s engineering expertise across the country.

“As this is green technology and software technology connected, then it’s not just about building a car but also focusing on green technology and future technology,” Kristel Leif, the CEO of Solaride, said. “Considering the world’s best solar-vehicle developers attend the event, including Bridgestone and Elon Musk’s Tesla, it’s also a good way of raising Estonia’s profile.”

As far as the organisers know, there has never been a solar-powered car developed in Estonia prior to Solaride. And when it set about developing its vehicle, it also learned first hand about the lack of engineers in Estonia. It’s an issue confirmed by a recent study that found that there is a significant lack of expert engineers in the country – a situation that could impact the economy in the coming decade.

By involving university students in Solaride, the project aims to groom a new generation of engineers.

“We have a big problem that is going to start to strongly impact our economy,” Leif says. “Many young Estonians don’t even know what engineering is, or they come from schools where it isn’t discussed much. So this idea has grown to be much bigger than just building a car. It’s a way to invest in the competency of engineers in Estonia.”

A strong university support

Solaride is an all-volunteer organisation and is heavily embedded in Estonia’s academic sector. Participants come from universities across the country – and the University of Tartu, Tallinn University of Technology and the Estonian University of Life Sciences are just a few financial backers. Solaride participants draw upon these university contacts as they prepare for the challenge.

The idea to participate in the World Solar Challenge actually originated with students in Alvo Aabloo‘s lab at Tartu.

“I told them that if they wanted to do something innovative, then this was a possibility,” Aabloo, a professor in the University of Tartu’s Institute of Technology, says. “I had no idea that it would take off with such energy. It’s been a big surprise for me.”

“There are different mentors and experts that help out in their respective areas of expertise,” Leif notes. In all, about 120 people are currently involved in the project, with an active core of nearly 50 people. These include electronics, mechanics, and software engineering teams, as well as teams engaged in fundraising, logistics, administration, and PR and marketing. There are also mentors, like Aabloo, who advises on specific questions or can point Solaride’s teams in the right direction when needed.

In March, Solaride received €180,000 from the Estonian government and the Tehnopol Science and Business Campus to support its activities. Ragmar Saksing, the head of green technology at Tehnopol, stressed in a statement Solaride’s “high potency with practical knowledge, contacts, finances and a test environment”.

Indeed, Leif notes that Solaride is one challenge that has allowed participants from different fields to collaborate. “Our education these days is often focused on speciality areas,” she says. “With Solaride, we have a single challenge where young people from different universities can work together to solve it and learn how to cooperate.”

Aabloo agrees. “Solaride is significant because it teaches different specialists to work together in a small business model,” he asserts. “They get a lot of practical knowledge that they wouldn’t get from university studies.”

Some students have even set aside work in companies to take part in Solaride, because they believe they can gain more practical experience from the project, Leif notes. “The experience they get here is more valuable than work in a large company,” she says. There are also opportunities for spinoffs, such as in the software sector, as solutions fashioned for Solaride can be applied in other contexts.

Delayed deadline

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has not only caused a delay in the World Solar Challenge, but obvious hiccups in the development of Solaride’s vehicle. As Leif points out, the team has been waiting for months for an engine to arrive from Australia. The project’s teams mainly communicate online using Slack and video calls.

“Physical contact is significantly less than it should be,” says Leif. “Half the team is in Tartu, half is in Tallinn,” she says. “Of course, it would have been more convenient to sit and work in the same garage, but restrictions have made that difficult.” Still, things have started to move, and the first generation of the group’s vehicle should be ready to roll by summer 2021.

With the new financing from the government and Tehnopol, the group will be able to secure desperately needed equipment, but it will need to continue its financing activities to achieve its goals. “We will certainly continue fundraising,” says Leif. “When we go to Australia in 2023, we might be going with the next version of the car.”

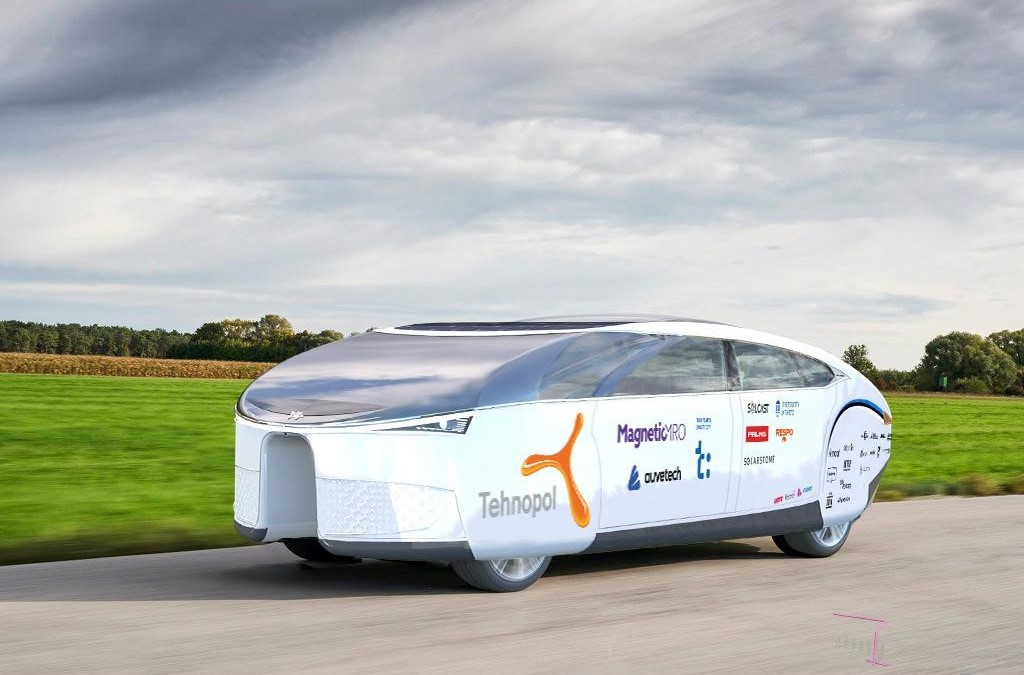

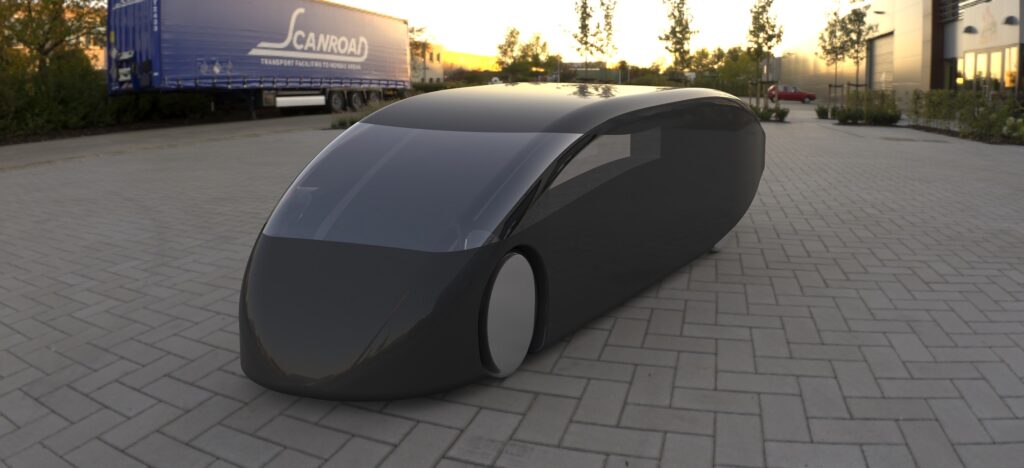

As far as the design is concerned, Leif says that it is being built to reduce wind drag and improve efficiency. While the envisioned car looks a bit futuristic, she notes that some contemporary solar car models, such as those made by Dutch firm Lightyear, aren’t dissimilar. “In a few years, it might be a completely normal look for a car,” says Leif.

Solaride is also cooperating with universities in Estonia to develop programmes to better engage students about engineering. “It’s important for Estonia, because our tech field is currently dragging because of the lack of engineers,” she stresses. “School curriculums need more practical output for the students to become good professionals. That is what Solaride is doing.”

Cover: One of the design proposals of Solaride’s solar-powered vehicle. Image by Solaride.