When South Korean clarinettist Soo-Young Lee joined the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra in 2014, she never imagined she’d still be here a decade later – or that Estonia would come to feel like home; drawn by chance, kept by curiosity, she now calls the slower pace, deeper silences and musical soul of Estonia essential to her art.

When Soo-Young Lee (39), a clarinettist born in Seoul, joined the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra – known as ERSO – just over a decade ago, the ensemble comprised musicians from four different countries. Today, the orchestra is far more international – a change she sees as a sign of progress. According to Soo-Young, this openness benefits not only the musicians, who gain from collaborating with artists of diverse backgrounds, but also Estonia as a whole. “When you are open to the world, the world becomes open to you.”

Self-confidence and curiosity are the two defining traits of Soo-Young’s character. It was with these qualities that she embraced the opportunity to begin her professional music career in a country she had barely heard of.

“After graduating from university in Seoul, I continued my master’s studies in Austria and Germany. During my final year, I began searching for an orchestra where I could play the clarinet,” she recalls. “At the time, I was especially drawn to playing with others. In many orchestras, positions were either limited or unavailable, but ERSO had an opening. I auditioned – and was selected.”

Since 2014, she has served as ERSO’s assistant principal clarinet, and in 2019, she became the section’s principal clarinettist.

Time moves more slowly in Estonia

When Soo-Young first arrived in Estonia, she knew little about the country and had few expectations. “It was mid-June, the sun was shining, and the yellow buildings of the Old Town looked like something out of a fairy tale. I immediately felt at ease,” she smiles at the memory. “People, of course, warned me not to celebrate too early – wait until you’ve experienced a proper winter, they said.”

One of the first things she noticed about Estonians was their connection with nature – something that resonated with her, as Koreans too feel a weekly need to escape to the mountains. Life in Estonia’s cities, of course, is far less hectic than in Seoul, a metropolis of ten million.

“Koreans don’t get much time off, but even so, they’ll drive five hours just to spend a day in the mountains. It’s a necessity,” she explains.

Compared with the fast-paced, material-driven, technology-saturated South Korea, Estonia feels more human, more natural and less automated. “Time moves more slowly here – and that’s exactly what an artist needs. Even if it’s just a single second, it passes more gently. Life in Estonia feels like meditation,” she says, almost poetically.

One aspect of Estonian life that initially surprised her was how hesitant people her age or older were to express themselves freely. “At first, I couldn’t understand it – how could you hold back your opinion just because others might disagree? I never questioned whether my opinion was right or wrong – I simply shared it.”

After living in Estonia for a decade and reading about its history, she now understands where that hesitation comes from. “Estonia and South Korea have similar pasts. While you suffered under Russian colonialism and aggression, we experienced something similar with Japan. Although the occupation in Korea lasted a shorter time, the repression was brutal. We weren’t allowed to speak our language. I didn’t grow up under that regime, nor did my mother – but my grandmother did.”

Nordic Estonia and exhausting work culture in South Korea

Today, cultural and diplomatic ties between Estonia and South Korea are stronger than ever. “Two years ago, Estonia opened an embassy in South Korea, and last year South Korea did the same in Estonia. That was a major step forward,” Soo-Young says, pleased that the two nations are building closer connections and exchanging more in terms of culture.

Still, Estonia remains relatively unknown in Korea. “Before moving here, I had never heard of Estonia – I didn’t even know where it was,” she admits. “These days, awareness is growing. While Estonia was once simply lumped in with the Baltics, it’s now increasingly seen as a Nordic country. More and more Koreans are working in Estonian tech companies – and they have even appeared on Korean TV. There’s growing interest in Estonia – especially in its digital society, which has caught the attention of our own government.”

Korean society, Soo-Young notes, is far more competitive – people live to work. “It’s a paradox, really. Traditionally we were an agricultural society, reliant on close collaboration. But growing up in Korea, I felt immense pressure – far more than I’ve ever felt in Estonia. And that pressure keeps increasing.”

She says the system engulfs people from an early age. “Once you fall out of the system, it’s very difficult to get back in or to survive financially. The education system is ruthlessly competitive – everything depends on academic success. South Korea has one of the highest rates of child depression and suicide in the world.”

She has no plans to return to live in Korea – the European lifestyle suits her better. Fortunately, she believes things are starting to improve post-COVID. “Economically, the pandemic hit us hard. But for society, it brought some blessings: people began to enjoy life more, to value their mental health. Families are no longer sacrificing themselves entirely for the success of one child. There’s less ‘helicopter parenting’ now, and people are learning how to rest.”

Galaxies and the infinite universe

Before committing to a career in music, Soo-Young seriously considered whether it was truly the path for her. “I’ve always had other interests – astrophysics, for instance. I was fascinated by planets and the cosmos,” she says. It was her mother who gave her the decisive push: “She told me that science would still be there later, but that I had to pursue music immediately, or I’d lose valuable time.”

“It was wise advice. Musicians work with their bodies – with muscles and breath – and the earlier you start, the more natural it becomes,” Soo-Young reflects. “I listened to her and continued with music. It was the best decision I’ve ever made.”

That said, her love of the stars hasn’t faded. “I still read about space and new planets. And I often wonder why I continue to devote myself to music. The answer is simple: because it has no end. You can do the same thing a million times – but it’s different every time. I can play a piece I first performed ten years ago and discover entirely new harmonies. It’s infinite – just like science, where nothing is ever truly final, because there is always more to discover.”

The clarinet’s voice touched her heart

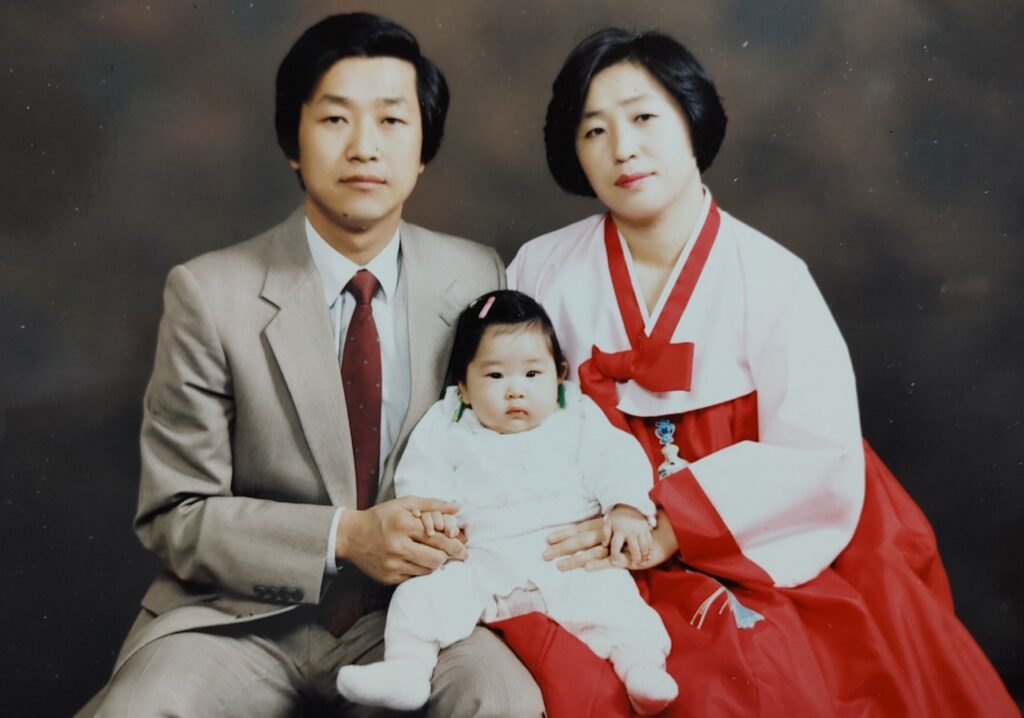

Soo-Young’s musical journey didn’t begin with the clarinet – she first played the violin. “My parents have always been lovers of culture and fans of classical music. When I was born, they wanted me to take up some form of art, believing it would enrich my life,” she says. “There was a violin teacher in our neighbourhood, so I started lessons at the age of five – just as a hobby. I studied for about eight years and came to really enjoy it.”

After her family moved to a different city, she continued studying violin in a new school. As her level was far above her peers, boredom set in, and she switched to the flute. “I really enjoyed the flute – it was even fun! But my mother encouraged me to try something else and enrolled me in an amateur wind orchestra.”

There, she began playing the flute – until the conductor intervened. “He said there were already too many flautists and asked if I’d be willing to try the clarinet. He sat me down and let me listen.”

“I was stunned by its beauty. The tone of the clarinet touched my heart – soft, warm, full of colour. I was captivated. It’s often said that the clarinet resembles the human voice, like the cello does. I didn’t know that at the time – but I felt it. I thought, what a fascinating sound – this is what I want to play.”

Seeing Arvo Pärt is like watching a tree grow

Of course, I couldn’t finish our conversation without asking about her favourite musician. “I enjoy the music of many different artists,” she replies. “What makes a musician special is their ability to transform the world around them, to interpret it through their own lens. Arvo Pärt possesses that gift. Every time I see him performing, or even entering a rehearsal, I see a tree growing – with invisible roots spreading deep underground.”

“He has an aura that inspires me,” she says with emotion. Once, while walking on the beach at Laulasmaa, she saw a swan – and immediately, Swan Song began playing in her mind. “Pärt transforms nature into something that reflects himself. In fact, he is nature, and nature is him,” she muses. “He’s something entirely unique – a phenomenon.”

When asked how well-known Pärt is in South Korea, Lee explains that his music is performed widely – in concert halls, television shows, and films. “When I lived in Korea, I didn’t even know he was Estonian – I assumed he was German, because his works were published by Austrian companies,” she admits. “It wasn’t until my first performance with ERSO, playing Credo under Tõnu Kaljuste, that I discovered he was Estonian. I was genuinely surprised.”

The article is part of the media programme “Estonia with many faces,” which highlights the richness and diversity of Estonian culture. The programme is supported by the Estonian Ministry of Culture and co-financed by the European Union.