As the West’s resolve over Ukraine weakens, a dangerous shift is unfolding – the aggressor is being rehabilitated while the victim is quietly pushed aside.

For the first four years of the Second World War, Germany revelled in the triumphs of its Führer, and the generations that followed – from the children of that era to their great-grandchildren – have lived with a lingering moral hangover ever since.

Psychologically, this condition is captured vividly by Heinrich Böll in Group Portrait with Lady, where the characters move through life under the invisible weight of crimes they did not personally commit but cannot escape. This post-war existence – Germans living as a nation “under observation” – became one of the most striking manifestations of collective responsibility in modern Europe. They rebuilt cities and lives, yet remained surrounded by the ruins of the past, feeling like defendants in the court of history.

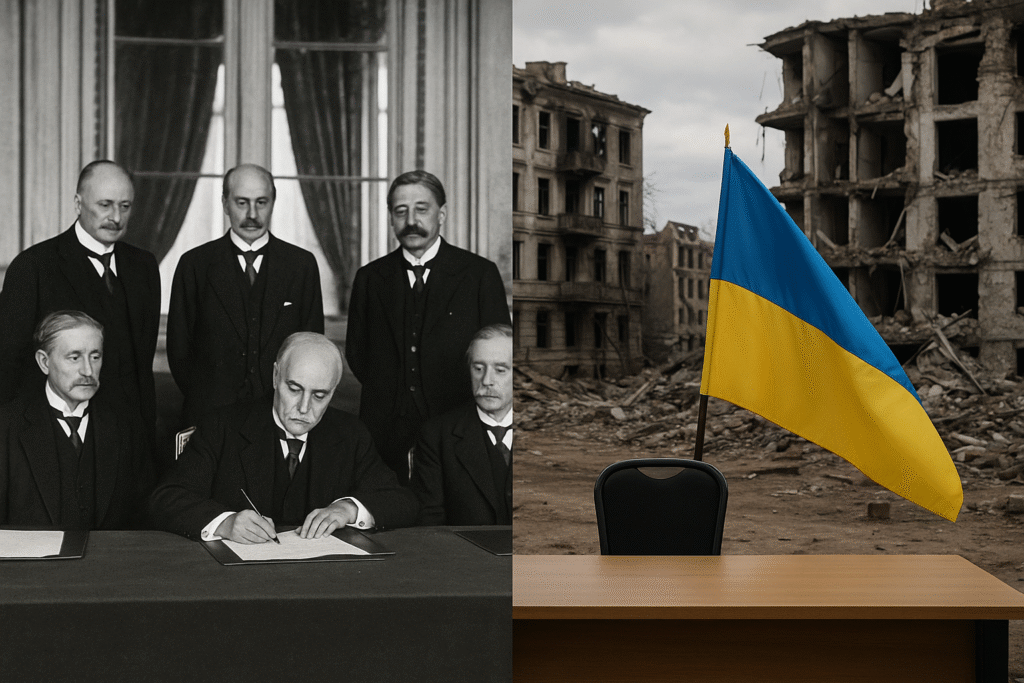

The scales of justice not tipped in Ukraine’s favour

When images of fires and explosions engulfing Ukraine filled television screens in 2022, many Ukrainians assumed something similar awaited Russia. The logic appeared unassailable: a state that launches genocidal warfare before the eyes of the world forfeits its right to normality. Economic isolation, diplomatic exile, cultural disgrace – Russia, we believed, would be pushed into its own post-imperial quarantine, as Germany had been after 1945. But the scales of justice did not remain tipped in Ukraine’s favour for long.

By the end of the second year of full-scale war, the tone of the Western press began to shift. The early moral clarity – Putin as war criminal, Russia as pariah – grew murky, muddled by markets, elections and fatigue. The days when Joe Biden could openly call Vladimir Putin “a killer” seem long gone. Today, no Western leader speaks of him in moral terms. He has returned to summit tables, indirect negotiations and the vocabulary of “strategic stability”. The arrest warrant issued by the International Criminal Court is now treated as an inconvenient footnote rather than a turning point in international law.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of Ukrainian civilians lie in graves and millions remain in exile, while Russia sells oil to India, gas to Europe through intermediaries, and weapons and nuclear technology to anyone who can pay. Sanctions are discussed less as instruments of justice and more as tools of leverage. Russia has not been ethically quarantined – it has been reborn, not only economically but morally.

Even the language has softened. What was once “aggression” is now “the conflict”. What were “atrocities” are now “concerns”. In Washington, Donald Trump even blames Ukraine’s president – not Putin – for starting the war. Emboldened by such cynicism, diplomats have begun to say the unthinkable aloud: the war will not end with justice, but with compromise.

For Ukrainians, this reversal is more than disappointing – it is existential. And here lies the danger – not only for Ukraine, but for Europe itself.

Treaty of Versailles inverted

If the war concludes on terms shaped by Trump, Erdoğan, Orbán, or any leader who prizes deals over principles, the outcome will not merely humiliate Ukraine. It will redefine geopolitics, replacing international law with the law of the strong. The nightmare scenario is clear: Ukrainians could one day awake to find that it is they – not the Russians – who have become Europe’s inconvenient people.

When a nation is not truly defeated but feels humiliated, its elites can harvest resentment like grain – a lesson tragically demonstrated by Germany’s humiliation after the Treaty of Versailles, which foreshadowed catastrophe.

The danger of a Trump-mediated peace lies in the inversion of that historical lesson. Instead of restraining the aggressor and protecting the victim, Europe may end up accommodating Russia while growing impatient with Ukraine. It is the path of amorality – pursuing advantage without principle – until, inevitably, it finds itself on the receiving end of injustice.

Psychologists such as Evelin Lindner have warned that collective humiliation is among the most potent fuels for future violence. Ukraine – if forced into concessions and reduced to a bargaining chip – could bear the emotional burden of an unfinished war: displacement, stigma, economic dependency and resentment.

There are always explanations – people can justify almost anything. Ukrainians are watching their place in the information landscape diminish. At the start of the war, European newspapers published essays about Bucha, Mariupol and Irpin almost daily. By 2025, reports of mass shelling in Ukrainian cities have slipped behind headlines about festivals, sport, AI and EU elections. The war in Ukraine has become an inherited complication, not a defining event.

The world now watches with agitation as Hamas returns the bodies of hostages to Israel or debates the length of a Trump–Macron handshake, while barely noticing another hospital destroyed in Ukraine, another murdered child, another inconsolable mother. It seems grotesquely unfair – even in a world already steeped in injustice.

Europe’s quiet retreat

Europe does not want another permanently wounded nation in its midst. It will choose a manageable silence. Refugees will be expected to return. Defence budgets will shrink. Patience for Ukrainian anger will fade. And over time, Ukrainians may begin to feel what Böll’s characters felt in the 1960s: that history has left them exposed, while the world has quietly crossed to the other side of the street.

Now reverse the lens. The world may come to view Russia not as a pariah but as a problem to be managed. And Russia will not be “the Germans of 1947”. It will become something far more comfortable for the West: a difficult neighbour to be tolerated.

But this coin has a reverse, and one day it may deliver a brutal surprise to Europe and the United States – when they find themselves confronting not a chastened Russia, but a state that considers itself victorious. By insisting that Russia is fighting not Ukraine but NATO, Putin is planting a poisonous seed of superiority in the collective mind of his nation.

The world has seen both before: the intoxication of imagined supremacy and the corrosive grievance of Versailles-style humiliation. Combined, they are catastrophic – especially when the future is being shaped by hands as crude and impatient as Donald Trump’s.

The opinions in this article are those of the author.

Unfortunately no one seems to realise that Putin is on an ego trip to bring back the USSR.Ukraine is only the first step