On a windswept block of East 34th Street, in the shadow of the Empire State Building and a short walk from the modest redbrick Estonian House, New York City has added a new name to its map: Ernst Jaakson Way; it’s an unassuming stretch of Manhattan real estate, but the idea behind it carries the weight of a vanished nation that refused to die – and the man who embodied that refusal.

On 18 November, Estonia’s foreign minister Margus Tsahkna presided over a crisp, formal ceremony inaugurating the street in honour of diplomat Ernst Rudolf Jaakson, the legendary Estonian statesman whose career spanned nearly eight decades. Standing before diplomats, city officials, and members of the Estonian-American community, Tsahkna spoke not only of Jaakson’s service but of something rarer: his defiance.

“Ernst Jaakson devoted his life to standing up for Estonia,” Tsahkna said, recalling how the diplomat kept the Estonian Consulate General in New York open through five decades of Soviet occupation. “He ensured that the legal continuity of the Republic of Estonia was preserved and that Estonia’s right to independence was not forgotten.”

In the vocabulary of foreign policy, “legal continuity” sounds almost bureaucratic. In practice, it was an act of stubborn, brilliant resistance. Jaakson was among the very few diplomats in the world who represented a country that – officially, on the maps of superpowers – no longer existed.

But he kept showing up for work anyway.

The man who outlasted an empire

Born in Riga in 1905 to Estonian parents with roots on the island of Hiiumaa, Jaakson grew up in a Baltic world still shaped by the upheavals of empire. He entered foreign service at 14 – an age when most teenagers are discovering hobbies, not foreign policy. By 1928 he had been assigned to the Estonian Consulate General in New York, a place that would become both his posting and his moral battleground.

When the Soviet Union annexed Estonia in 1940, most Estonian diplomatic missions were closed or absorbed. But in New York, Jaakson kept the lights on. He worked in a twilight zone of international law – operating a consulate for a country that, according to Moscow, no longer existed.

That he could continue at all was due to the US policy of non-recognition, articulated in the 1940 Welles Declaration, which refused to acknowledge the Soviet takeover of the Baltic states. It was a policy more often cited in academic texts than in headlines, yet for Jaakson it was oxygen: it meant Estonia could maintain a diplomatic footprint on American soil. It meant that someone – somewhere – officially spoke for the Estonian Republic.

“He was one of the very few diplomats in the world representing a country under foreign occupation,” Tsahkna noted in New York. “Our diplomats today follow in Jaakson’s footsteps.”

A consul in the age of the Moon

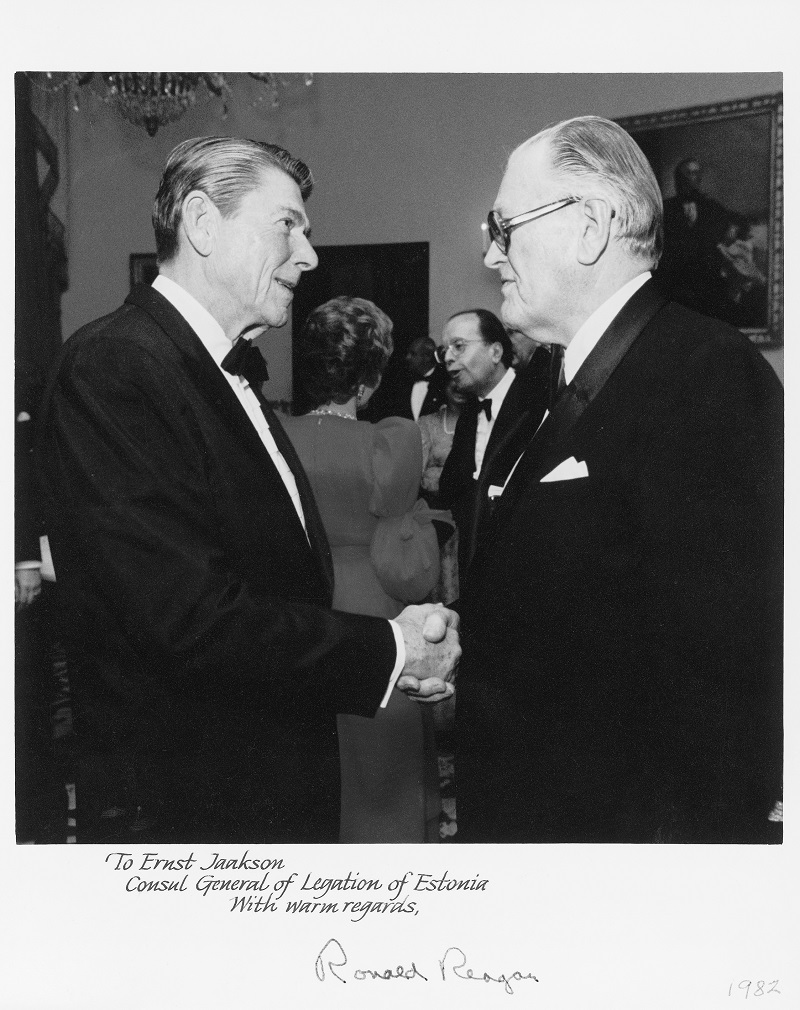

Jaakson’s office on East 34th Street became a kind of secular shrine for Baltic exiles, diplomats, and American officials. He met presidents from Lyndon B. Johnson to Ronald Reagan, quietly reminding Washington that Estonia had not been absorbed, only imprisoned.

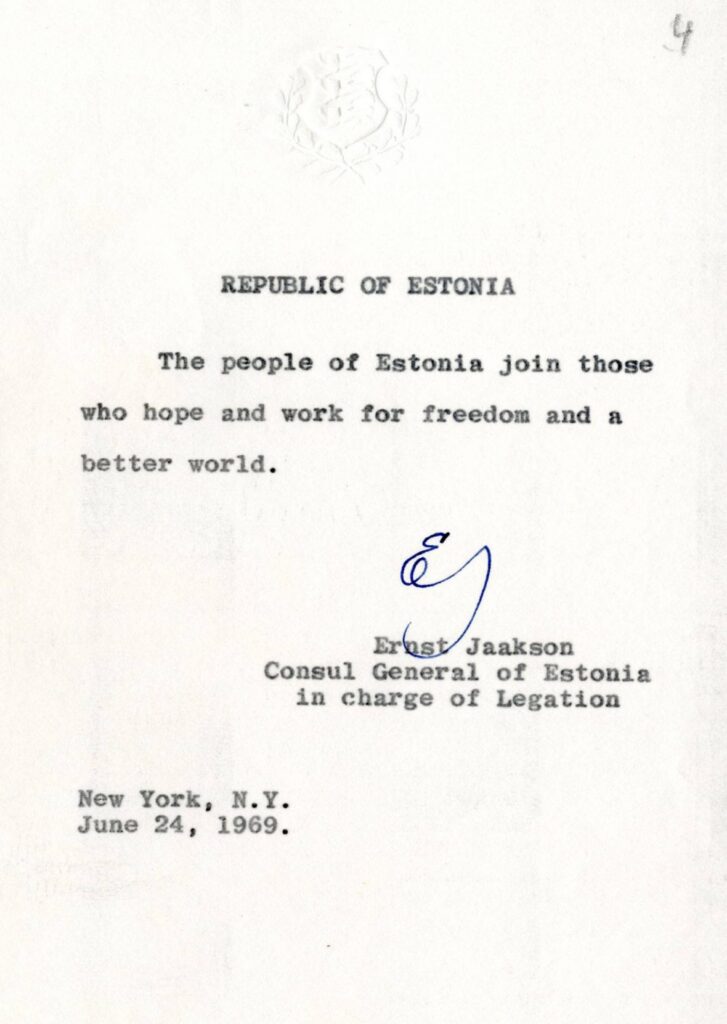

Sometimes history bends in ways that feel almost literary. In 1969, NASA sent a request to foreign governments to provide messages of goodwill for the Apollo 11 crew to take to the Moon. Estonia had been occupied for nearly 30 years by then – there was, officially, no Estonian government to reply.

So Jaakson wrote the message himself.

“The people of Estonia join those who hope and work for freedom and a better world.”

“The people of Estonia join those who hope and work for freedom and a better world.” Credit: the Estonian foreign ministry.

That simple line – etched onto a silicon disc alongside messages from 73 other nations – traveled to the lunar surface. Even as the Soviet Union insisted Estonia did not exist, its words reached the Moon.

If diplomacy is the slow art of keeping hope alive, Jaakson became its most patient practitioner.

A nation in exile, and a community sustained

Throughout the Cold War, Jaakson maintained close ties with the Estonian diaspora. He visited refugee ships in American ports after the Second World War, reassured newly arrived families, and helped nurture the cultural networks that sustained Estonian identity abroad.

He supported the founding of ESTO, the global Estonian cultural festival launched in 1972 in Toronto, which brought together exiles, émigrés, and second-generation youth who knew Estonia only through stories. Through it all, Jaakson served as a quiet anchor – proof that the Estonian Republic, though occupied, was not extinguished.

Inside his New York office, portraits of independent Estonia hung on the wall for decades, their subjects aging only in memory.

The return of the flag

Then came 1991. Estonia’s independence was restored, the Soviet Union was dissolving, and the world Jaakson had defended from exile suddenly materialized again.

At 86, he was appointed Estonia’s ambassador to the United States and permanent representative to the United Nations. In November that year, he presented his credentials to President George H. W. Bush – a ceremony that must have felt less like a diplomatic formality than a personal vindication.

He would later return to New York as Consul General, serving until his death in 1999.

“It is a major tribute to Jaakson’s life’s work,” Estonia’s ambassador to the United States Kristjan Prikk said at the street-naming ceremony. “A clear example of the strength of the Estonian–US alliance.”

Why a street matters

New York is littered with honorary street signs – scraps of geography that commemorate the city’s mosaic of communities, histories, and diasporas. But naming a street after an Estonian diplomat is something different. It is an act of geopolitical memory in a city that thrives on amnesia.

For Estonia, Ernst Jaakson Way is a public reminder that small nations can punch above their weight, that sovereignty can survive even when territory is lost, and that one person – armed only with a letterhead, a seal, and an unwavering sense of legitimacy – can hold a nation open across half a century.

For New York, it’s a nod to the city’s long, improbable role as a sanctuary for political persistence.

And for the world, at a moment when borders and democracies again feel fragile, it is a quietly radical message: sometimes history is kept alive not by armies, but by a single diplomat who refuses to disappear.