Thirty years ago today, president Lennart Meri went on TV to announce an audacious plan: connect every Estonian school to the internet; it started as an ambassador’s proposal, survived scepticism about teachers and bureaucracy, and helped lay the social groundwork for Estonia’s later “digital state”.

On the evening of 21 February 1996, Estonia’s president Lennart Meri addressed the nation on television with a promise that sounded wildly ambitious for a country only five years removed from Soviet rule: Estonia would bring its schools into the digital age.

The young state was short of money and long on urgent priorities. Roads, public services and institutions were being rebuilt almost simultaneously. Yet Meri framed the initiative not as a luxury but as a survival strategy. Quoting Francis Bacon – “knowledge is power” – he added the line that became Tiger Leap’s unofficial motto: “Whoever is late will miss out.”

The project became known as Tiger Leap (Tiigrihüpe in Estonian): a nationwide effort to place computers in schools, connect them into networks, train teachers and build learning materials. It was not just a technology programme. It was a wager that a small country could modernise quickly by raising the baseline skills of an entire generation.

Tiger Leap matters because it helps explain something often reduced to branding: how Estonia became a place where digital systems are not a showroom trick but everyday routine – and why the “digital state” was, from the start, as much about schools and teachers as it was about machines.

An idea that arrived by email

Tiger Leap didn’t begin with Meri’s broadcast. Its early public spark came a year earlier, on 14 February 1995, when Jaak Vilo – now a professor of bioinformatics at the University of Tartu – circulated a note to an email list connecting Estonians.

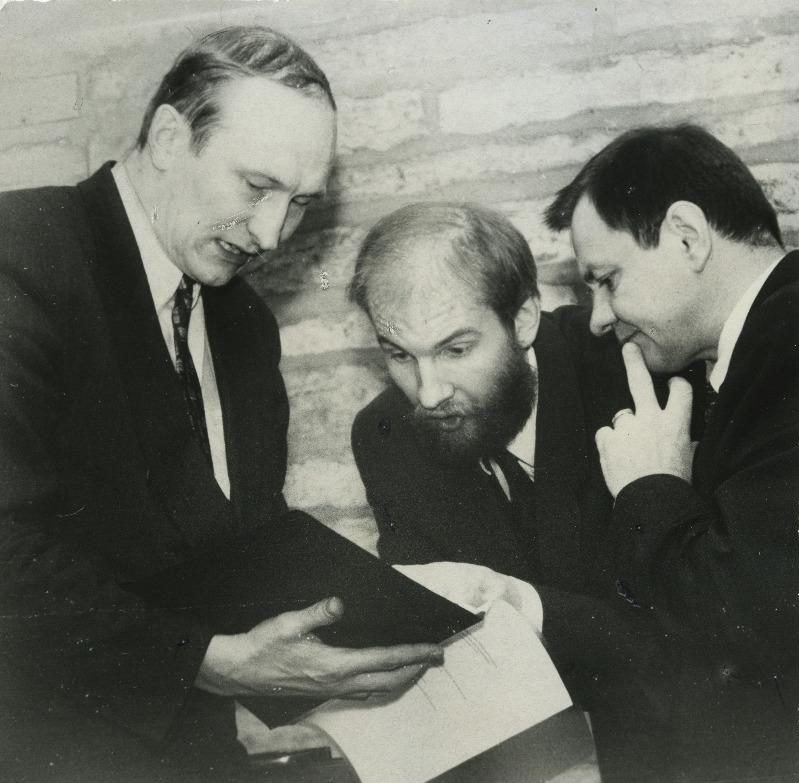

He pointed readers to a front-page article in Rahva Hääl, an Estonian daily: the country’s ambassador to the United States, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, had proposed equipping Estonia’s upper secondary schools with computers. The timing was awkward and the ambition unmistakable. Estonia was rebuilding everything at once, and a national technology programme could sound either visionary or reckless.

But Ilves’s argument was strikingly concrete. Estonia’s upper secondary graduating cohorts totalled about 17,000 students, he noted. That meant 17,000 computers could – in principle – give broad access and raise a national floor of digital competence. He imagined students getting access for roughly a quarter of the day, and he promised more than better schooling: a societal upgrade. Estonia could “leap into the 21st century with both feet” and become “a completely different country.”

Ilves explained that the idea crystallised after he signed, in the course of his official duties, a World Bank-related loan agreement involving Estonia and then read an analysis of why thirteen successful countries had done well. The common thread, he said, was a large share of technically educated people. If Estonia lacked the money for heavyweight industrial policy, it could still build human capital – quickly – by treating schools as the launch pad.

He even offered a first price tag: $10–15 million (or 110–165 million Estonian kroons). For Estonia at the time, it was huge. It also proved optimistic as the full scale of the task became apparent.

The blunt reality: networks, rooms, security – and teachers

The early reactions were not starry-eyed. In 1995, Estonia’s minister responsible for education and culture, Peeter Olesk, backed the ambition but insisted that “reality” had to be confronted. If computers were bought, schools would need network connections, secure rooms and a plan for how the machines would actually be used in teaching. None of that was cheap.

Ilves himself identified what he saw as the project’s Achilles heel. Asked where it could fail, he replied with a sigh: “Teachers, of course. Children will learn to use computers; a large proportion of teachers will not.”

The education press quickly turned the debate into practical terms. Some commentators focused on the technology: buying standalone PCs without networking, they argued, would be close to pointless – even negligent. Others worried less about cables than about the state’s capacity to deliver, warning that a large public budget could simply breed a new layer of bureaucracy, slow everything down and leave schools receiving yesterday’s computers years too late – a dark joke that, in many places, has proved uncomfortably accurate.

Those criticisms ended up shaping Tiger Leap’s design. If the programme was going to work, it couldn’t just be about hardware. It had to be about connectivity, and it had to move faster than classic state procurement often allows.

Microsoft, backlash, and the scramble for a workable structure

In November 1995, Lennart Meri travelled to the United States with Estonian businesspeople and announced plans involving Microsoft: a joint working group to help equip Estonian schools with computers. It sounded, externally, like momentum.

At home, it exposed a familiar weakness in young states: overlapping mandates, unclear lines of authority, and institutions still learning how to coordinate. Senior figures in the country’s emerging IT and policy ecosystem complained publicly that key bodies had not been consulted, and local media soon reported that the promised working groups had yet to materialise – a small but telling sign that ambition alone would not be enough without a workable structure.

From Washington, Ilves sounded both distant and pragmatic: it was hard to organise things from 6,000 kilometres away, he noted, but he expected the project would move. The episode mattered because it showed Tiger Leap wasn’t inevitable. Estonia had ambition – and also friction.

A new minister – and a committee with a school student

Political turbulence accelerated the sense that something had to be decided. The “tape scandal” around interior minister Edgar Savisaar contributed to a government collapse; a new government took office. A new minister of education and culture arrived: Jaak Aaviksoo.

Aaviksoo moved quickly. He travelled to the US on 20 November 1995 to discuss Estonia’s computerisation with business and finance circles. Soon after, he established the National Steering Committee for the Computerisation of the Education System – a small piece of institutional engineering that became important.

Its membership offered a snapshot of Estonia’s emerging tech-policy network: Ilves; Ants Sild, an early IT entrepreneur; Tanel Tammet, a researcher; and Leo Võhandu, a professor – and, strikingly, Sten Tamkivi, then a 17-year-old upper secondary student from Tartu who would later become a senior figure at Skype. Aaviksoo wanted a student’s perspective, so decisions weren’t made solely by older officials imagining what young people needed.

The committee’s job was to convert a slogan into a plan: strategy, funding and a structure capable of delivering.

From plan to rollout: the foundation moves fast

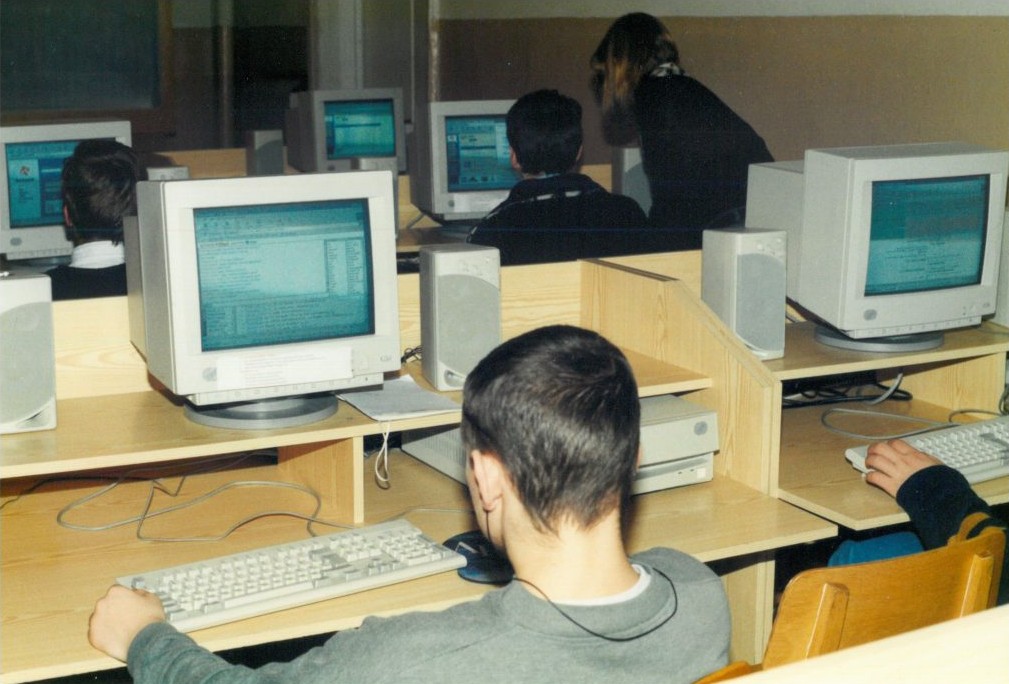

After Meri’s February 1996 broadcast, the programme solidified into a three-year first phase (1997–1999) with explicit goals: internet-connected computers in schools (roughly one workstation per 10–20 pupils), upgrades to the education network EENet, and teacher training at scale.

The budget grew. Ilves’s early estimate of $10–15 million gave way to official projections of 465 million kroons over three years, funded from multiple sources, including the state budget and international programmes. The first-year allocation ended up lower than requested – 35.5 million kroons rather than 50 million – but it was enough to begin.

A crucial choice followed: implementation through a dedicated body rather than leaving everything inside a ministry. In February 1997, the Tiger Leap Foundation was established, with Enel Mägi – recruited from the Open Estonia Foundation – becoming the project’s substantive leader. Her job was the unglamorous core of state-building: rules, procurement, criteria and the practical question of who gets what, when.

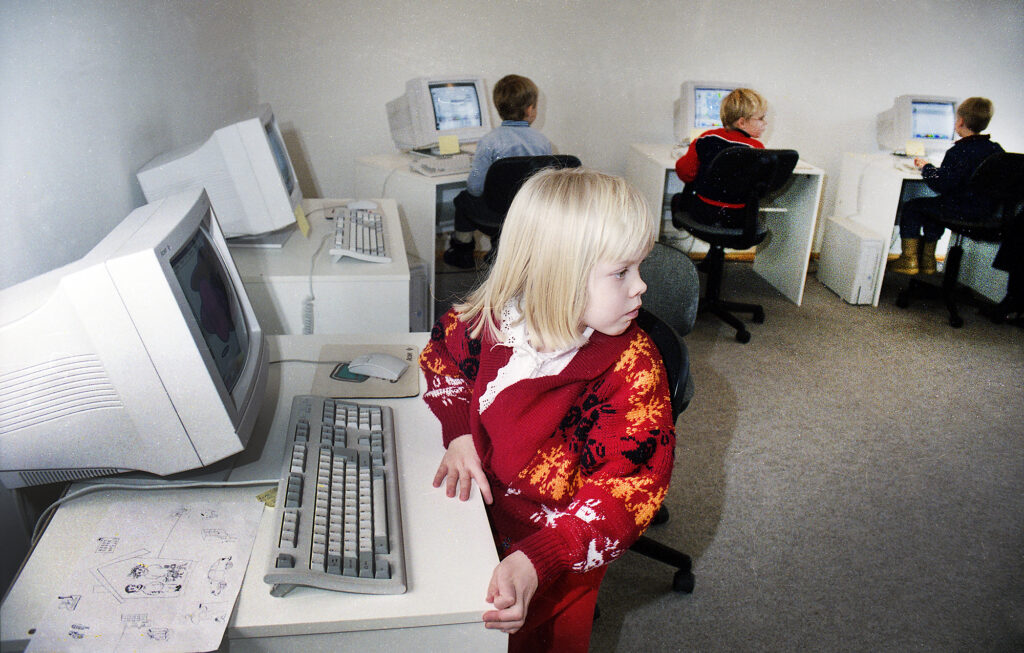

The foundation also understood politics. In August 1997, it brought 100 computers to Tallinn’s Town Hall Square for a free public event, giving many people their first hands-on experience of the internet. Shipments reached schools; teachers trained; and a subsidised scheme helped teachers acquire home computers.

By the late 1990s Tiger Leap had become a national story, not just a government line. The Tiger Tour in August 1998 took banks of computers around Estonia to show what the internet could do; about 25,000 visitors practised basic skills such as email and web pages.

The Tiger Tour in August 1998 took banks of computers around Estonia to show what the internet could do.

In 1999, funding continued, and by early 2000 the central goal had been achieved: all Estonian schools were connected to the internet, albeit unevenly.

What Tiger Leap really changed

It’s tempting to tell Tiger Leap as a tale of hardware delivered and cables laid. But its deeper effect was generational. It helped normalise the idea that computers and networks belonged in ordinary public life – and it trained enough teachers and students to make later digital reforms socially possible.

Years later Ilves visited a start-up in Tartu and asked how its founders began. One replied: “I was a Tiger Leap child.” It is a neat anecdote, but also a serious measure of policy impact: a state project that didn’t just buy equipment, but helped create the people who would go on to build what Estonia is now known for.

Thirty years after Meri’s broadcast, Tiger Leap looks less like a tech miracle than a lesson in governance: focus on connectivity, treat training as infrastructure, and build an institution capable of moving at the speed your ambitions require.

And above all, remember Meri’s warning – the one that still applies well beyond Estonia: whoever is late will miss out.