In “Expats corner” we catch up with foreigners who live or have lived in Estonia, to find out what they really think of the country. Justin Petrone is a writer and blogger, originally from New York, who has been living in Estonia on-and-off for ten years.

Justin, what brought you to Estonia?

A ferry brought me to Estonia. It was a late August afternoon, warm, the passengers sat around on the open decks and ate their lunch or played cards until the rocky archipelago of Helsinki gave way to the waves, and then we floated on toward that odd stretch of the gulf where you see no land anywhere. At last, the tree line started to form, and I could see the spires of the churches and the clumps of houses. I had a pretty good guide, too, during that whole first journey. I had met her in a program for foreign correspondents. An adventurous type. She had lived in Tallinn for a long time and showed me around. I still have that ferry ticket. I keep it in my wallet.

Had you heard about Estonia before and what was your preconception about Estonia?

When I was a boy, I was sick in bed and my grandmother came to visit me. She gave me a book – children’s stories of the Second World War, which was something that any sick child in the 1980s would have really desired. There was the Italian girl whose father was in an internment camp and had his fingernails ripped out, and the Czech boy Pavel, to whom something really awful happened but I can’t remember what.

And then there was an Estonian girl who talked about rationing and how she enjoyed having a cold, because the snot from her nose would add a savoury saltiness to her tasteless soup. I also remember reading about how she would get a piece of bread with a teaspoon of sugar on it as a dessert sometimes. That part made me hungry and that was the first time that I heard of Estonia.

Preconceptions? I guess I imagined it would be like Prague, with the squares and architecture and good cafes and pretty people. But also lots of post-commie rot and 1980s haircuts. That’s what Prague was like in 2001. You’d go into a club and they’d still be playing “Hungry Like the Wolf“. Maybe they are still playing it now. In a lot of supermarkets in Estonia you can walk in today and they will be playing A-ha’s “Take on Me“. There’s something about new wave music that sets the mood in these places.

What were your first impressions?

I’ll be honest, each time I return to Estonia from somewhere else, I feel I am entering some barbarian, pagan, Viking realm. That’s how it felt that first time and that’s how it feels now. They can build all the gadgets and glass towers they like and get all their clothes at H&M – it makes no difference, because they are the same people deep down.

I’ll give you an example. I visited relatives in Italy about a year ago, staying in these little villages that were founded by the Ancient Greeks, where the people are relaxed and sit around the piazzas telling stories, and the mere process of eating is a well-thought-out, multicourse affair with salads and pastas and poultry or fish dishes and desserts and coffee, followed by that very necessary shot of limoncello.

Then I flew back to the snowy north where I used a shovel to dig out my car at the airport parking lot. On the way home, we stopped at Viikingite küla, a themed restaurant outside of Tallinn, where the staff all wear medieval garb. There was a big roaring fire going there, the skins of animals hung on the wall, a dog was sniffing our feet. And what’s to eat? A cut of meat, some potatoes with sauce, some boiled root vegetables, and a beer, or a coffee, and that’s it. It’s just that Olde Hansa (a medieval restaurant in Tallinn – editor), Viimne Reliikvia (an old Estonian movie – editor) vibe. It lingers. My brother-in-law Aap is this big, burly guy and even though he’s mild-mannered and nice to me, I have no trouble imagining him wielding an axe.

How easy was it to integrate into Estonian society?

It depends on how you perceive the process of integration. If you learn the language and get a grip on the understated, sarcastic humour, and familiarise yourself with local customs, like hitting your partner with birch branches in the sauna, at just the right spot, with that learned flick of the wrist that produces the right velocity, striking with just the right force, then you might fit in a little bit.

Have you learned Estonian?

Jah, muidugi.

What kind of friends do you have? Local or other expats? Is it easy to make friends with Estonians?

Most of my friends are other expats and so-called väliseestlased, “foreign Estonians”. I have managed to make friends with some Estonians, but, usually, by the time they become my friends, I have long since forgotten to think of them as anything other than regular people. Another issue is that so many Estonians are actually half Swedish or half Ukrainian or half Egyptian or something, so it’s hard to see them as being “just Estonian” or representative of “Estonianness”. I will say that there are some truly creative, innovative individuals living in Estonia and I am proud to know and associate with them.

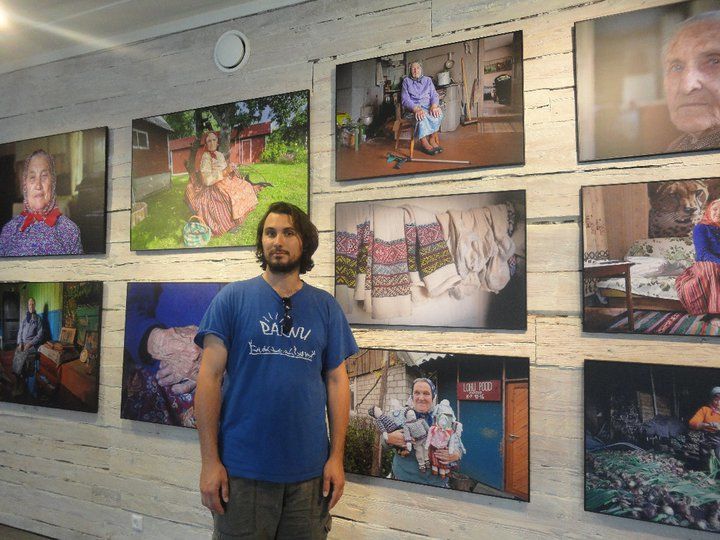

What do you do now in Estonia and do you feel that it’s a right environment for you, professionally speaking?

I am a writer, and writers can write anywhere. And even if you are writing anywhere, you are often heading somewhere else to write about something else. But I have been in Estonia long enough to get it into my bones, and it’s a comforting place to be and to write. It’s also inspirational – I have written three books about Estonia and working on two others at the moment.

The first project is another My Estonia book and the second is a novel about a fictional existentialist writer named Jaak Naplinski. It’s going to delve into the issue of what value 1960s ideals have in today’s hypermaterialistic society. I call it The Naplinski Paradox. I have some other projects brewing and should be heading to Iceland at some point to do some research for another novel. That book won’t be about Estonia, but it still will have as its setting a bleak, trying northern place, and I am sure my experiences in Estonia will help a lot.

How does Estonia inspire you in your writing?

I have been very lucky to be surrounded by creative, driven people in Estonia, starting with my wife, Epp, who has written travel memoirs, books for children, books about the environment. She’s like a force of nature and it’s awesome to see her work, although it can be intimidating. I tell myself, “Don’t worry, Justin, she’s a few years older, so she has a head start.”

And there are others: Mike Collier, the British-Latvian writer, who lives down near Võnnu, or the elusive Vello Vikerkaar. The list is long. How about Fred Jüssi, the naturalist!? To sit at his kitchen table and hear his stories, to realise that this man spends as much time as he can in the wilderness, just listening to waterfalls or photographing birds. I have a book of his and I read it over and over again, and each time I read it, I feel that I become a better writer, just by digesting his thoughtful words.

Or how about Kristiina Ehin, the poet? Reading her words is like getting lost in the Estonian forests in spring. Once when I was in San Francisco, I went into City Lights, the famous independent bookstore, and pulled out the latest collection of European fiction, and who should be included but Kristiina? I think if you are in a US literary market, especially a place like New York, you will feel very hopeless at times, and many other sensible people will no doubt ask, “Why do you even bother trying?” But when you are that close to it, like I have been in Estonia, then you really get the sense that, “Okay, I am good enough, this is something I can do.”

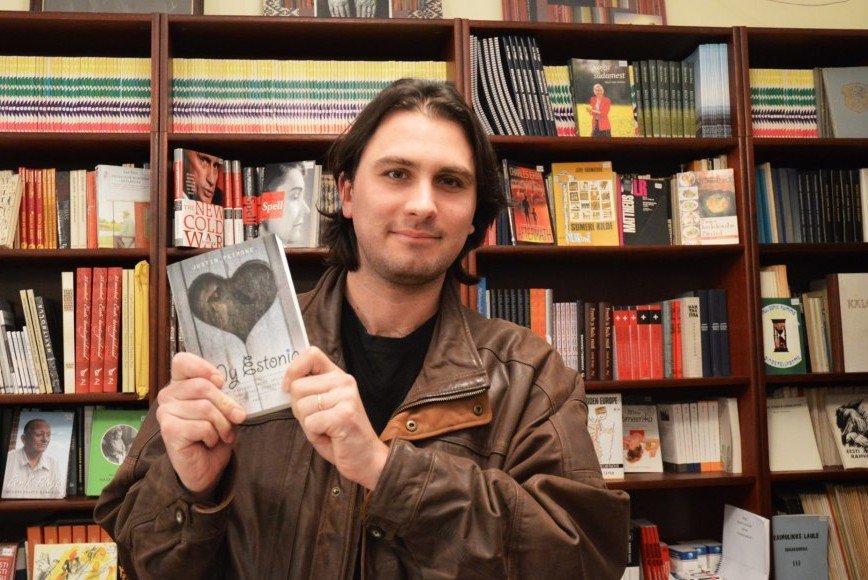

What has been the feedback to your book, My Estonia?

My Estonia is the first book I wrote and writing a book is not an easy task for anybody. When I finished it and it came out, I hoped it might crack the top ten on the strength of people’s interest in Estonia. Then it went on to become a number one book for many, many months. Suddenly, I was walking down the street and people would just yell out my name, or I’d be sitting on the bus next to someone reading a book, and then realise that, “Wait a second, he’s reading My Estonia.”

So, I was wholly unprepared for the phenomenon it became, this terrific reaction where I am getting letters from people in Japan or Brazil whose Estonian friends gave them My Estonia, and were really touched by our story. I cannot say if it is a good book, a great book, a terrible book, but it’s certainly been a widely read book, in some circles, and of course I have been very grateful for this response, because it has encouraged me to write more.

Estonia has been open for change for over twenty years. What do you feel has changed the most since you moved to Estonia?

I remember these creaking trams with old floors covered in melting ice and mud, a downbeat feeling of exhaustion, a sort of grey cloud that seemed to hover in perpetuity over the city of Tallinn when I lived there a decade ago. And like so many people I was drawn to the sparkle of shiny new things, glistening new hotels and apartment buildings, just because they were material signs of change. Do you remember how small Tallinna Kaubamaja (a department store in Tallinn – editor) was back then? And Stockmann (another department store – editor) seemed like a shopper’s paradise, a little spot of civilisation in the muck. Do you remember what the Rottermani kvartal (a former industrial area, now turned into shopping and business district – editor) used to look like? Those depressing ruined industrial port buildings?

The whole city of Tallinn, and a lot of Estonia, too, has undergone an incredible facelift. Even living in Viljandi, I saw an old liquor store transferred into a hip cafe, a vacant apothecary turned into a cafe and organic foods store. And the Folk Music Centre, this great, glorious space, wasn’t even there ten years ago. While these are just physical changes, the people within those shops and buildings have also changed. They are more optimistic, more energetic. Maybe it is generational change, too. Young people today have little memory of the Soviet era, if any. Meantime the people who were adults during the Stalinist era are few and far between, so that sense of heavy, weary fatalism is gone. These days, there is more energy, more action, and I like it.

The whole city of Tallinn, and a lot of Estonia, too, has undergone an incredible facelift. Even living in Viljandi, I saw an old liquor store transferred into a hip cafe, a vacant apothecary turned into a cafe and organic foods store. And the Folk Music Centre, this great, glorious space, wasn’t even there ten years ago. While these are just physical changes, the people within those shops and buildings have also changed. They are more optimistic, more energetic. Maybe it is generational change, too. Young people today have little memory of the Soviet era, if any. Meantime the people who were adults during the Stalinist era are few and far between, so that sense of heavy, weary fatalism is gone. These days, there is more energy, more action, and I like it.

What do you dislike the most and what do you like the most about Estonia?

The level of alcohol consumption is clearly a public health problem as well as a public nuisance. “Drunks” are seen as a part of life, though, and people are quite tolerant of them, “because they don’t hurt anybody”, most of the time. But they affect us. Too many of our relatives are afflicted by alcoholism and it hurts me to see my children exposed to public displays of drunkenness. My daughter would go to play hide-and-seek near her school and then run home because there were some drunks walking down the street. It hurt me because she was so young and already knew what a drunk was. When you are a parent, you want to protect your child from the more awful side of life, you know.

So, that’s a dislike. What I like about Estonia is the reverence with which creative people are treated. In some countries, being a writer makes you an outcast, but in Estonia, if you write a book, a good book, then they hold you up on high. When an artist says something here then it often matters because just by being an author or a poet or a musician, whatever he or she thinks carries that extra weight. Put it this way: If you are running for president or prime minister, you can get all the political endorsements you like, but when Tõnis Mägi (an Estonian singer-songwriter – editor) sings “Koit” (his most famous song) on your behalf, then you know you’ve really won the election.

What should be done differently in how the country is being run in your opinion?

I am intrigued by the idea of Estonia taking the same approach to implementing progressive environmental policies as it did with its focus on information technology. These days they talk of a Silicon Valley on the Baltic, and an e-state, or e-riik, but perhaps the country could be an eco-state, or an ökoriik, as well. I just saw an article headline from someone advocating alternative energy sources. “Russia can turn off Europe’s gas, but it can’t turn off Europe’s winds.” I agree.

Would you consider staying permanently in Estonia or are you planning to return to your home country?

I think I’ll always be traveling between both because I love both of them. One leg here, one leg there.

An ECO ECONOMY?!?!?!?! Really??? You have to bring bad ideas along with you? Doesn’t the wasteland of failed green energy everywhere else discourage you even a little? Or is it that you must be politically progressive to make it as an author?

What type of person tells the good people of Estonia that they should really consider going back to the workers paradise. Because that is where government wasteful spending takes you.

Whatever the reason, I hope to GOD they ignore that nonsense and continue to be economically successful. And of all things, you site “wind.” If you had even the slightest understanding of the terrible economic and habitat impact realities associated with these disruptive eyesores, you would have kept quiet.

They should try some off shore fracking! A good start.

I may be moving to Tallinn soon. I will spread the good word of capitalism. I will fit in just fine.