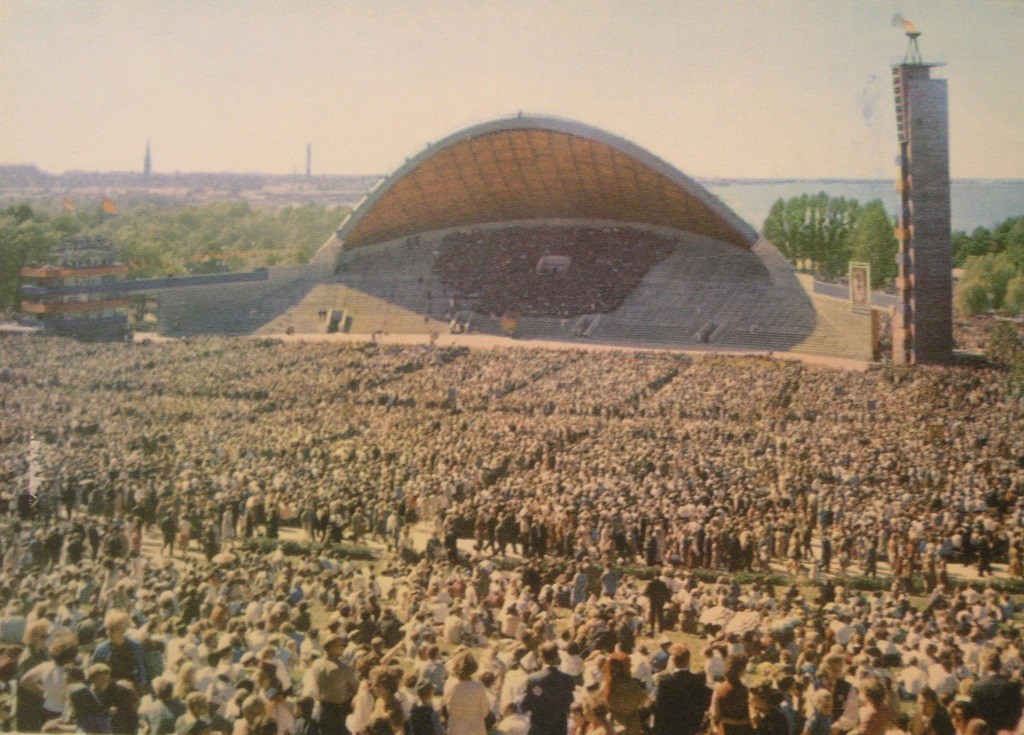

The Estonian Song Celebration (Laulupidu) is a cultural phenomenon that, every five years, unites a vast choir for a single weekend in July; approximately 100,000 spectators gather to witness the concerts – many joining in as beloved national songs echo across the grounds.

More than 41,000 performers from across Estonia and abroad will take part in the XXVIII Song and XXI Dance Celebration from 3 to 6 July, with the 2025 festival, titled “Iseoma” (“Authentically Ours”), highlighting regional dialects, local character, and the vitality of folk tradition.

The festivals have long served as a cornerstone of Estonian identity. On two occasions, the Song Celebrations have played a pivotal role in the country’s path to independence.

In the 19th century, choirs and song festivals stood at the heart of the national awakening among Estonian peasants, who discovered the value of their own language and cultural heritage through collective singing. This awakening, and the forging of a national identity, ultimately led to the declaration of independence in 1918.

Following the Second World War, during the decades of Soviet occupation, the Song Celebrations helped preserve the nation’s cultural spirit. In 1988, several hundred thousand people gathered at the Song Festival Grounds, singing for freedom over many days and nights. This Singing Revolution was instrumental in the collapse of Soviet rule and paved the way for Estonia to regain its independence in 1991.

The timeline below charts the key moments in the evolution of this singular Estonian tradition.

Song Celebration timeline

1869

The first Estonian Song Celebration took place in Tartu, featuring 878 male singers and brass musicians. All the songs were performed in Estonian.

The event was initiated by the publisher Johann Voldemar Jannsen, a key figure in the Estonian national awakening. For many of the participating peasants, it was a revelation: their folk traditions could take their place alongside the so-called high culture of Europe.

Jannsen’s daughter, Lydia Koidula – whose pen name means “Lydia of the Dawn”– wrote the lyrics for two of the songs performed: Sind surmani and Mu isamaa on minu arm, both of which remain in the repertoire to this day. Known also as Koidulaulik, or “Singer of the Dawn”, she played an active role in preparing the musical scores and raising funds for the celebration – an exceptional position for a woman in the 19th century.

Sind surmani is based on a poem by Lydia Koidula, while the modern version of the song was composed by Alo Mattiisen, with additional lyrics by Jüri Lesment.

1880

The third Song Celebration was held in Tallinn for the first time, marking a shift towards the capital. A year later, Finland followed suit by organising its first nationwide song and music festival.

1891

The fourth Song Celebration marked the first appearance of mixed choirs. Despite efforts by the Russian tsar to impose the dominance of the Russian language in public life, more than half of the songs were performed in Estonian – including works by Miina Härma, Estonia’s first female composer.

Singers spontaneously joined in the now national anthem Mu isamaa, mu õnn ja rõõm (“My Fatherland, My Happiness and Joy”) by Fredrik Pacius. In the years that followed, choral singing remained the only cultural sphere in which Estonian could be publicly used, as the imperial authorities required all official matters and education to be conducted in Russian.

1894

For the first time, choirs from Estonian settlements in Russia took part in the fifth Song Celebration, held once again in Tartu. Pacius’s anthem Mu isamaa, mu õnn ja rõõm was sung once more, reaffirming its growing symbolic significance.

1896

From the sixth Song Celebration onwards, the festivals have been held in Tallinn, establishing the country’s capital as their permanent home.

1910

The festival was held in Tallinn, featuring children’s choirs among the performers for the first time. Mihkel Lüdig, who served as artistic director and introduced a more demanding repertoire, led the celebration. His composition Koit (“Dawn”) remains the traditional opening song to this day.

1923

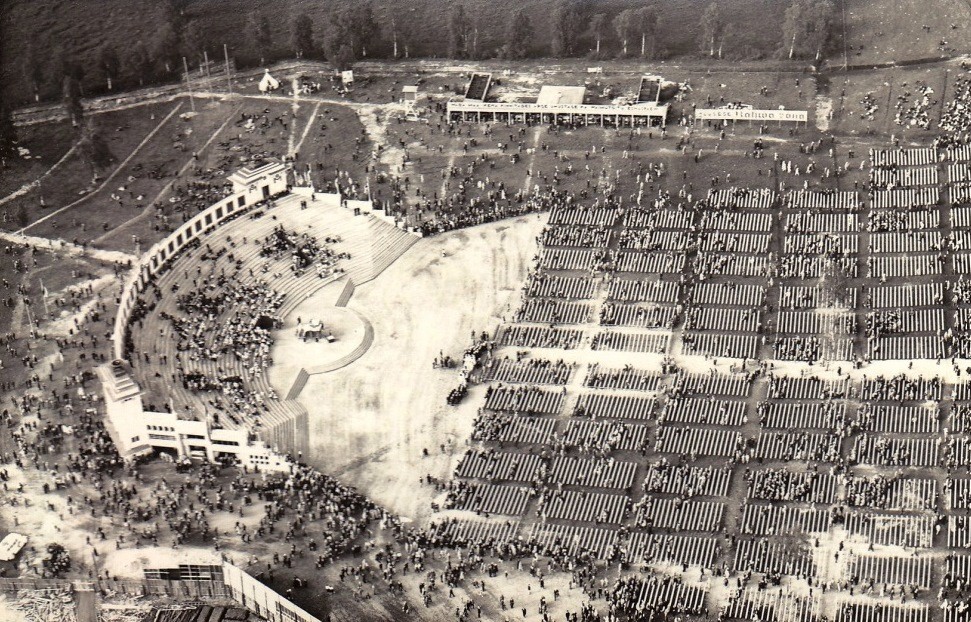

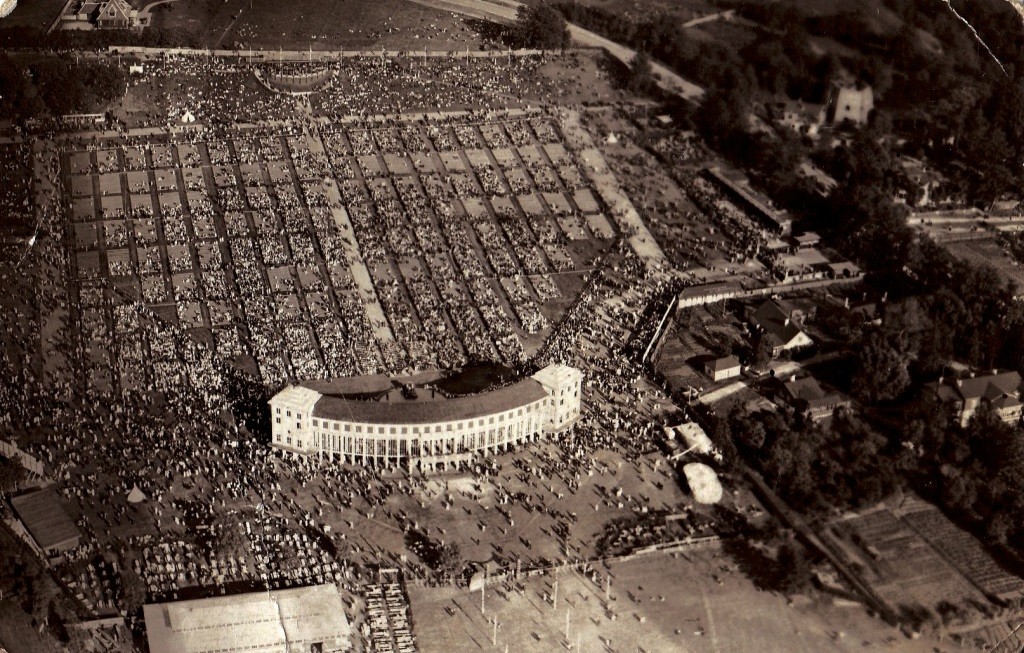

The eighth Song Celebration – the first in independent Estonia –was held on a newly constructed permanent stage in Tallinn, capable of accommodating 12,000 singers. It marked several firsts: the celebration was captured in the first aerial photograph and filmed for the first time.

With the 1923 festival, the tradition of holding the Song Celebration every five years was established.

1928

The ninth Song Celebration was the first to be held at what is now the Song Festival Grounds in Tallinn. A new stage, designed by architect Karl Burman, accommodated 15,000 singers.

1933

Female choirs took part for the first time, and the festival was broadcast on radio for the first time, bringing the celebration to listeners across the country.

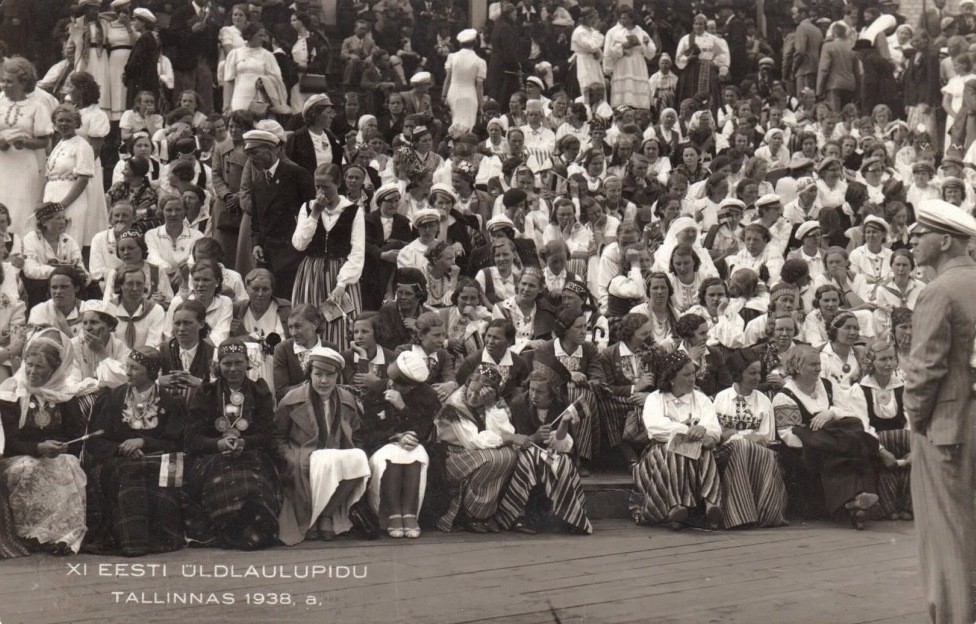

1938

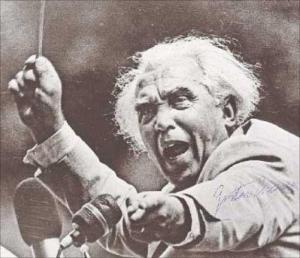

At the eleventh Song Celebration, Gustav Ernesaks conducted the massed choirs for the first time, and his music was included in the programme.

In 1944, while in deportation in Russia, he composed the melody for Mu isamaa on minu arm (“My Fatherland Is My Love”), set to the lyrics of Lydia Koidula. Just five days later, Soviet forces bombed Tallinn, destroying the Estonia opera house, the national broadcasting centre, the conservatory and numerous other cultural landmarks. That same year, more than 70,000 Estonians fled westward, among them many prominent musicians.

In 1946, the first major Estonian Song Festival in exile was held in Germany. In the years that followed, similar festivals were organised in Sweden, the United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom – keeping the tradition alive far from home.

1947

The twelfth Song Celebration – the first held after the war – took place under Soviet occupation, with Gustav Ernesaks serving as one of the artistic directors. Despite the heavy hand of Soviet propaganda, the repertoire remained largely traditional, offering a subtle form of cultural resistance.

Ernesaks’s Mu isamaa on minu arm was performed for the first time, quickly becoming an unofficial anthem of national endurance. Yet the atmosphere was tense: arrests were made even at the Song Festival Grounds.

In 1950, a new wave of Soviet repression struck the Estonian cultural sphere, with Song Celebration artistic directors Alfred Karindi, Riho Päts and Tuudur Vettik among those targeted.

1950

The thirteenth Song Celebration marked the darkest chapter in the festival’s history. Soviet propaganda songs dominated the programme, and among the participants were choirs of Soviet miners and a Red Army ensemble.

Amid the repressive atmosphere of Stalinist rule, choral singing remained one of the few cultural spheres where private initiative and mutual trust could still survive. This quiet resilience helped to sustain the nation’s longing for freedom.

Despite the schizophrenic nature of the event – national in spirit, yet hijacked by imperial ideology – most Estonians continued to regard the Song Celebration as the most cherished and meaningful expression of their national identity.

1960

By the fifteenth Song Celebration, a new stage –designed by architect Alar Kotli – had been completed, offering improved acoustics and space for the massed choirs. In a telling sign of the times, Mu isamaa on minu arm was removed from the official programme before the concert.

Yet the choirs, defiant and undeterred, began to sing it spontaneously. After a brief pause, Gustav Ernesaks stepped up to the conductor’s podium and took the lead. From that moment on, the song became the emotional climax of every Song Celebration – an unofficial anthem and an enduring symbol of the Estonian spirit.

1969

The seventeenth Song Celebration marked the centenary of the tradition. For the first time, a ceremonial flame was lit in Tartu – the birthplace of the celebrations – and carried across Estonia to Tallinn.

The repertoire reflected a notable return to tradition, standing in contrast to the Soviet propaganda-laden programmes of the preceding and following festivals. Mihkel Lüdig’s Koit (“Dawn”) was performed as the opening piece, establishing it as the traditional beginning to the celebration ever since.

1972

Exiled Estonians organised the first ESTO – an international gathering of the Estonian diaspora – in Toronto, Canada, with a global Song Celebration as its centrepiece. At the same time, Estonian dissidents sent a letter to the United Nations calling for the restoration of the country’s independence.

By the late 1970s, the geopolitical climate had darkened once more. Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, many young Estonians were conscripted into the Red Army, deepening the sense of unrest and resistance at home and abroad.

1980

The nineteenth Song Celebration formed part of the cultural programme of the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games – an event boycotted by much of the free world in protest against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

In the lead-up to the festival, the Soviet authorities intensified their crackdown on dissidents. Amid growing political and artistic repression, two of Estonia’s most renowned musicians – composer Arvo Pärt and conductor Neeme Järvi – emigrated to the West, joining the cultural exodus in search of artistic freedom.

1985

The twentieth Song Celebration featured a wide array of participants, including male, mixed, female and boys’ choirs, as well as Russian choirs, brass bands, violin ensembles and choirs of Russian war veterans.

Of the 82 songs on the programme, only 48 were composed by Estonians – reflecting the continued Soviet efforts to dilute national culture within the broader ideological framework.

1988

In May, Alo Mattiisen’s Five Patriotic Songs were performed at the Tartu Pop Music Days, striking a powerful chord with the public. The following month, the Singing Revolution began in earnest at the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds.

Night after night, thousands gathered for spontaneous singing demonstrations – an outpouring of national unity and defiance. In time, the crowds swelled to several hundred thousand, their voices rising in unison to demand freedom.

The Singing Revolution began in earnest at the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds in 1988.

1990

Although Estonia was still formally part of the Soviet Union, the twenty-first Song Celebration was marked by a powerful resurgence of national symbols and traditional repertoire.

The concert concluded with Mu isamaa, mu õnn ja rõõm – the former and now restored national anthem – despite its long-standing ban under Soviet rule. Just over a year later, on 20 August 1991, Estonia regained its independence.

1994

The twenty-second Song Celebration was the first to take place after the restoration of Estonia’s independence and marked the 125th anniversary of the tradition.

1999

Young children’s choirs took part for the first time, adding a new generation of voices to the tradition. President Lennart Meri captured the enduring spirit of the event, declaring: “The Song Celebration is not a matter of fashion. The Song Celebration is a matter of the heart.”

Although Estonia was now independent and its cultural identity no longer under threat from foreign rule, the Song Celebration remained a cherished expression of national pride and collective joy – something to be preserved for generations to come.

2003

The Song and Dance Celebrations of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were inscribed on UNESCO’s List of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, recognising their cultural significance and role in preserving national identity across generations.

2004

A statue of Gustav Ernesaks was unveiled at the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds, honouring the composer often regarded as the father of the modern Song Celebration.

Although heavy rain forced the cancellation of the official procession, singers and dancers spontaneously joined the march, answering the call of maestro Eri Klas – testament to the enduring spirit and unity of the tradition.

American filmmakers Maureen and James Tusty began work on a documentary exploring the Estonian Song Celebrations and the pivotal role of singing in the country’s struggle for freedom.

The Singing Revolution premiered on 1 December 2006 at the Black Nights Film Festival in Tallinn, bringing international attention to one of the most remarkable non-violent movements in modern history.

The filmmakers reflected: “We had made the film for the rest of the world, but we could think of no better venue for our international premiere. We were deeply touched by the fifteen-minute standing ovation the Estonian audience gave us. It is not just a story about Estonia – it’s also a story about humankind’s irrepressible drive for freedom and self-determination.”

Hirvo Surva conducted the united choirs at the 2004 Estonian Song Celebration.

2009

“To breathe as one”: beginning with this festival, the Song Celebration embraced not only music but also a message of shared values – the first of which was the connection between generations. The phrase “to breathe as one” (ühtehingamine) entered the Estonian language as a powerful new idiom.

In a moment of spontaneous unity, singers initiated a wave of raised hands that rippled from the top of the stage to the very back rows of the audience – an ecstatic fusion of performers and spectators, symbolising a nation in perfect harmony.

2014

“Touched by Time. The Time to Touch.” A record-breaking 42,000 singers, dancers and musicians filled three days with music, movement and emotion.

The first concert of the Song Celebration, held on 5 July, guided the audience through a musical journey spanning the entire history of the event – from its origins in 1869 to the present day. The second concert, on 6 July, featured a seven-hour musical marathon, blending classical masterpieces with newly commissioned works created especially for this milestone celebration.

Ta lendab mesipuu poole (“He Flies Toward the Beehive”) performed at the 2014 Song Celebration.

2019

The XXVII Song and XX Dance Celebration was entitled “My Fatherland is My Love”. A total of 1,020 choirs took part in the Song Celebration, comprising more than 35,000 singers. The youngest participant was five-year-old Emma Kannik from Musamari Koorikool in Tallinn, while the oldest was 90-year-old Aino from the New York Estonian Choir.

The smallest choir, with just 12 singers, was the Kauksi Primary School Choir, while the largest was the European Estonian Choir with 123 singers. The latter was not the only expatriate group – 25 Estonian choirs from abroad and 17 foreign choirs also performed at the celebration.

The Dance Celebration featured 713 dance groups, including 15 Estonian expatriate groups, with a total of 11,500 dancers – making it the largest Dance Celebration in history.

Mu isamaa on minu arm (“My Fatherland Is My Love”) performed at the 2019 Song Celebration.

2025

More than 41,000 singers, dancers, musicians and folk performers from 1,869 ensembles are set to take the stage at the XXVIII Song and XXI Dance Celebration, taking place from 3 to 6 July. According to initial figures, over 31,000 will participate in the Song Celebration and nearly 11,000 in the Dance Celebration, joined by some 800 folk musicians.

This year’s festival, titled “Iseoma” (“Authentically Ours”) – a term evoking one’s own roots and authenticity – shines a spotlight on regional dialects, the unique character of local communities and the raw vitality of folk tradition.

Beneath the iconic Song Arch, more than 31,000 singers and instrumentalists from 990 collectives will gather. These include over 6,000 performers from selected pre-school choirs, more than 2,400 from boys’ and mixed boys’ choirs, 5,300 from children’s choirs, 4,000 from women’s choirs, 1,300 from men’s choirs, and 10,800 from mixed choirs. They will be joined by a brass band of 1,500 musicians and a symphony orchestra numbering 900 players. In total, 788 conductors will lead the ensembles in what promises to be one of Estonia’s most moving cultural spectacles.

* This article was originally published on 4 July 2014, in collaboration with Life in Estonia magazine. It was lightly edited and amended on 4 July 2019 and 3 July 2025.

1969 I had planned a trip to Europe right around July 4th. My father said if I left a few days early and went to Estonia first he would pay half my air fare. Sold. I had no idea what to expect. I don’t remember them saying all that much about the song festival. I spent Saturday afternoon and Sunday at the festival grounds. It was positively awesome – the colors, the music, the crowds – spectacular.