Estonia’s cherished Song Celebrations take place under the famous arch at the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds – but how was the arch built?*

The first Song Celebration stage at its current location in Tallinn was built in 1928. It was designed by Karl Burman and provided space for 15,000 performers.

The choirs sounded powerful there, but their voices would not reach the other side of the grounds. In 1957, a competition was held for designing a new song arch.

Estonia was, by that time, occupied by the Soviet Union, but the communists wanted to use the new arch for their own advantage – to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic (as the Soviet-occupied Republic of Estonia was called) in 1960. The competition was won by architects Alar Kotli, Henno Sepmann and Endel Paalmann.

A unique solution for its time

Kotli imagined the song arch as a bugle and made a cardboard model to depict that. In order to bring it into life, Heinrich Laul’s help was sought. Laul was heading the department of engineering at Tallinn Polytechnic Institute (now the Tallinn University of Technology), whose career made him one of the most outstanding Estonian engineers and building scientists of the 20th century.

Laul said that, in order to achieve the character of a bugle, the song arch needed two arches: one in the back and one in the front. At the same time, it was important that the first arch would not have pillars and would be “suspended in air”. Otherwise, the singers’ access would be limited.

People who have visited the song arch are now probably asking, where the second arch is. The second reinforced concrete arch leans on the columns of the back wall, and the partly concrete-filled steel pipe hangs on cables between the first and second arch. According to Karl Õiger, Professor Emeritus of the School of Engineering at TalTech, achieving this solution was complicated and unique, at least for that time.

The cables exceeding the guarantee period by nearly three times

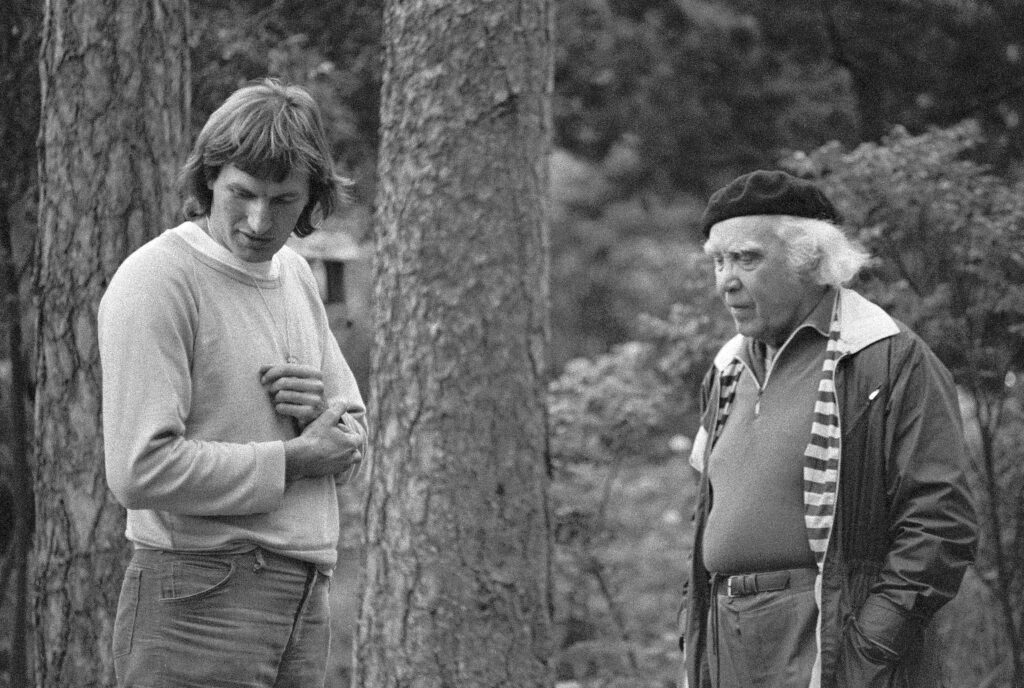

The durability of the structure was tested at the Polytechnic Institute under the guidance of Laul. Õiger, who was a student there at the time, recalled that when developing different projects, they first created a model and then started testing it in the lab under load. They would then assess the environmental effects on the structure.

The whole weight of the roof is directed towards the front and back arches by 12 hollow suspension cables and stabilised by 19 additional curved cables. The diameter of the three-layered closed cables is 38.5 millimetres (1.51 inches).

According to Õiger, five or six large construction companies would not dare to take the risk to manufacture the cables. “What if it fails, they would say,” he recalled. Luckily, one bridge building company was ready to risk it, but gave only a 20-year guarantee. In reality, the same cables are still in place 59 years later.

In order to assess the state of the cables after exceeding the guarantee period by nearly three times, one suspension cable was recently removed and replaced with a new one, so that the old one could be examined from the inside. Through lab tests, scientists concluded that the existing cables can surely be used for another 20–25 years. However, the wooden constructions of the song arch roof were completely replaced in 2019 and the cables were cleaned and protected against corrosion.

A symbol that must be preserved

For Õiger, the song arch is not merely a building, but represents a symbolic value.

“During the Soviet times, that was the place one could go and speak their mind about how Estonian people felt about things. If normally we would have to sing about Lenin, then here, we would eventually sing the songs of (Gustav) Ernesaks,” he said. “The song arch is a symbol that has to be preserved at all costs!”

Ernesaks was a well-known composer and a conductor during the Soviet occupation, who, among other tunes, composed the “anthem” of the Soviet-occupied Estonia.

With grand buildings, like the song arch, Õiger also motivated his engineering students, by noting that the results of their labour would visible for everyone – and if they did a good job, their work would last decades or even hundreds of years. “I would recommend that young people follow the words of Horace: ‘Exegi monumentum!’ – I built myself a monument.”

* This is an edited version of the article originally published on the TalTech website. The article is based on the interview with Karl Õiger in the TV documentary, With Wit and By Hand: A Hundred Years of Innovation (Mõistuse ja käega: 100 aastat innovatsiooni), and the book, Tallinn University of Technology 1918–2018. The article was originally published on 26 July 2019.

Cover: The famous arch was renovated for the 2019 Song Celebration. Photo by Aivar Pihelgas.