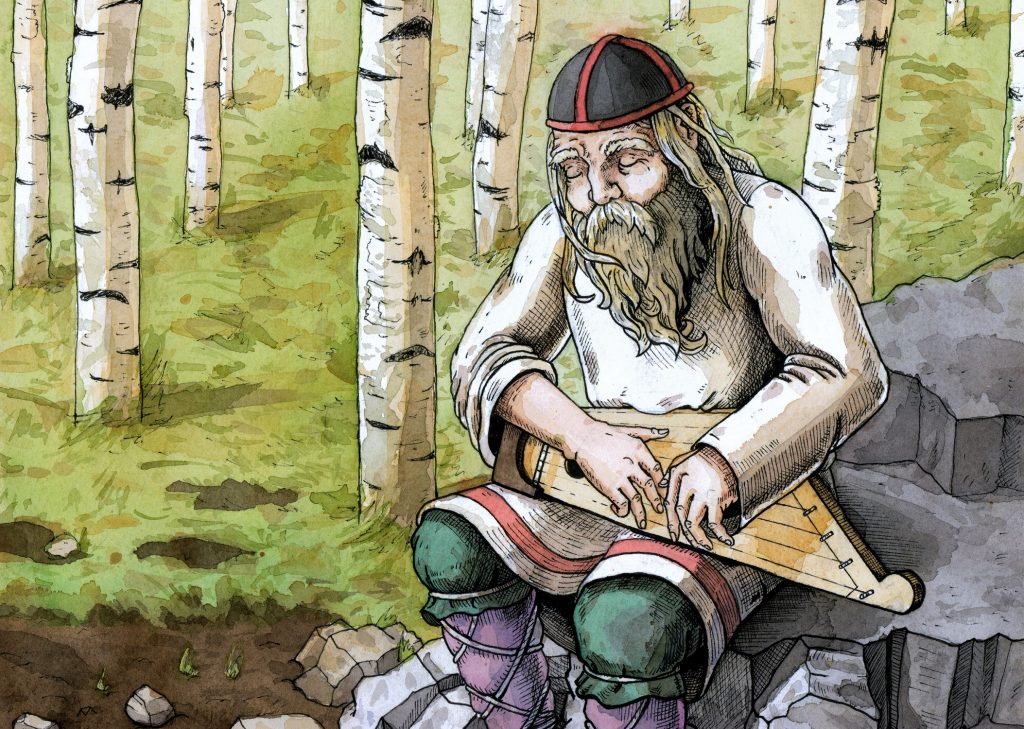

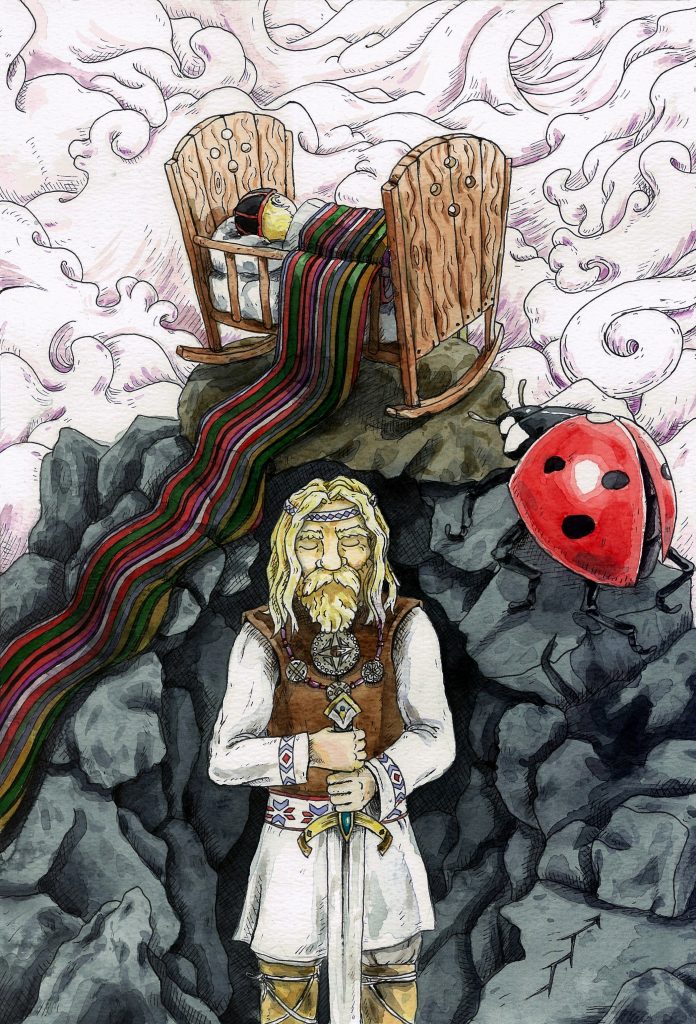

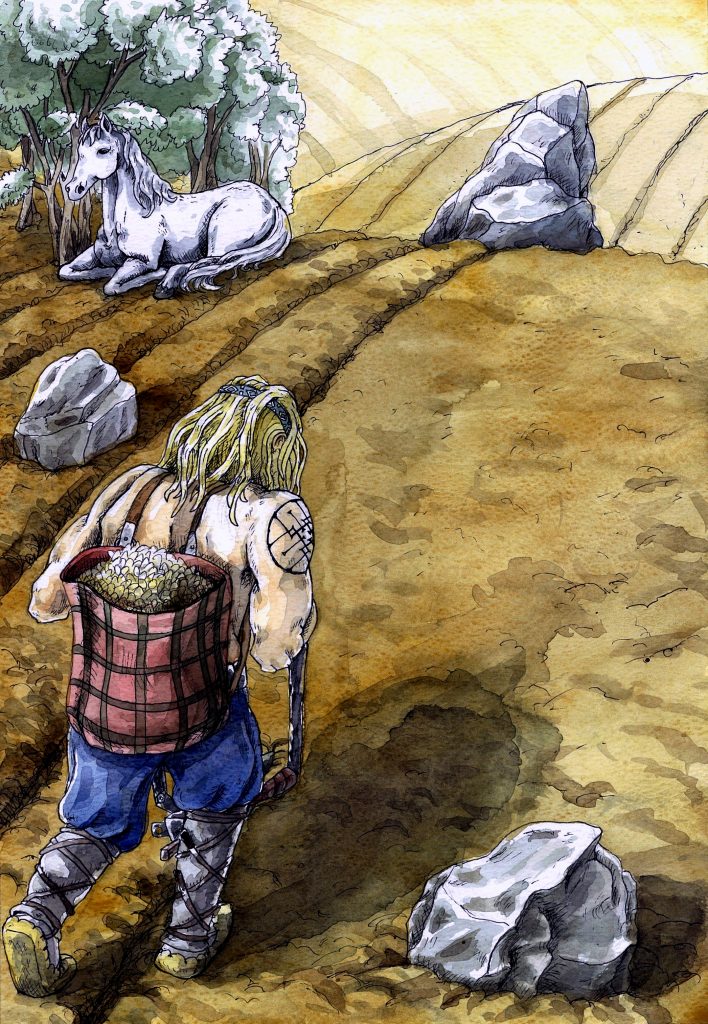

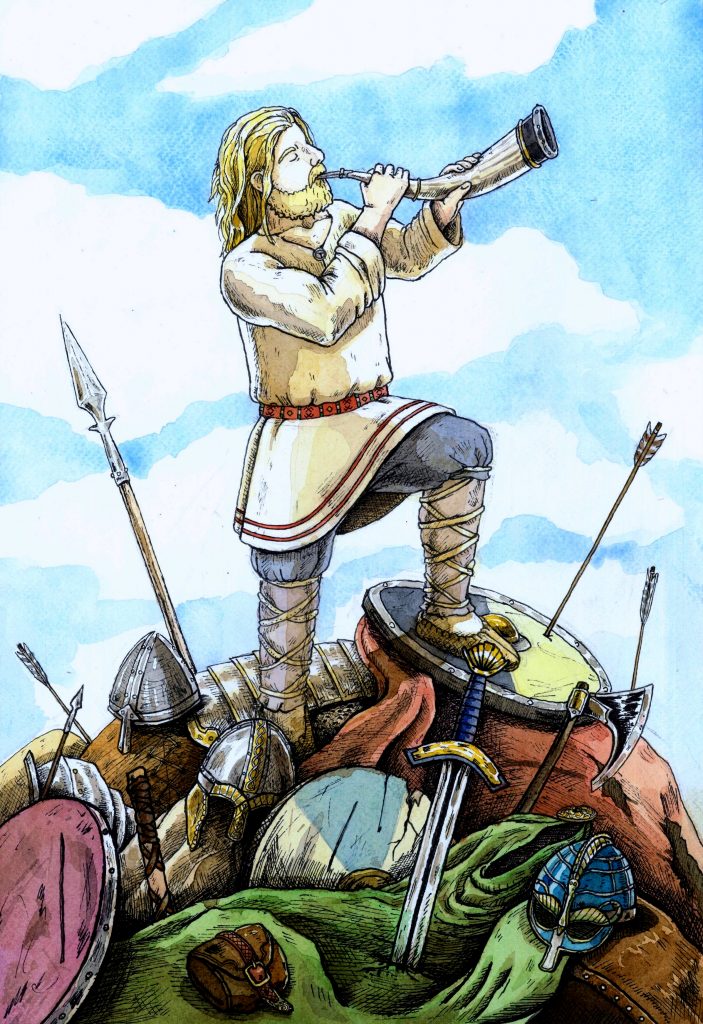

Joan Llopis Doménech from València, Spain, was inspired by the Estonian national epic, Kalevipoeg, and created new illustrations for it while studying at the Estonian Academy of Arts; in an interview with Estonian World, Doménech explains his interest and work.

What brought you to Estonia?

During my last year of studying fine arts at the Universitat Politècnica de València, I decided to enrol onto Erasmus (a European Union-funded programme that helps students study abroad – editor).

I’ve always felt very interested by the northern countries and fascinated by their landscapes – since I was a child, I wanted to travel far away. I began to feel a lot of curiosity about Estonia. Going there was one of my best decisions – I fell in love with the Estonian nature, it doesn’t disappoint.

The truth is that Estonia exceeded my expectations. The first impression was stunning, all the medieval atmosphere in Tallinn amazed me. During the first months, I felt like in a dream, everything was so surprising and beautiful, I was really excited about my new life in Tallinn.

How did you find your experience, studying in Estonia?

At the Estonian Academy of Arts, I discovered my true path – the illustration world. The ambience was very inspiring and I felt very creative. I’m very grateful also to all the teachers for giving me the support for my Kalevipoeg illustration project – putting their trust in me and appreciating my illustrations, even saying that they seemed to have been created by an Estonian. Studying there provided me with new perspectives, aims, approaches and motivation.

What made you to choose the Kalevipoeg story for your illustrations and how did you discover it in the first place?

In fact, I discovered Kalevipoeg even before coming to Estonia. I love to research about mythology and ancient tales – although, at the time of my discovery I didn’t yet foresee the illustration project.

Then, once in Tallinn, I used to go a lot to the chess club at Paul Kerese Malemaja. As a chess player in Spain, too, I really enjoyed playing with Estonian players – and even trying my luck in some tournaments. I used to talk a lot with the chess teacher, Ervin Liebert, who explained to me a lot about the Estonian traditions and culture – I learned a lot from him and really appreciate all his help. He gave me, as a present, the book, “Cuentos Tradicionales Estonios” (“Estonian Traditional Tales”), compiled by Jüri Talvet and adapted to Spanish by Albert Lázaro and Esther Bartolomé. That book was the key – I was so impressed about the Estonian tales and realised it could be a great idea and an interesting aim to illustrate the Kalevipoeg tale as my final degree work.

How did you do your research?

I started asking my Estonian friends, to learn about their opinions and views about what Kalevipoeg meant for them, and the relevance of the story in their former schools and childhood. Also, I had an interesting conversation with a salesperson at one of the local book shops and then I felt quite confident about starting the project.

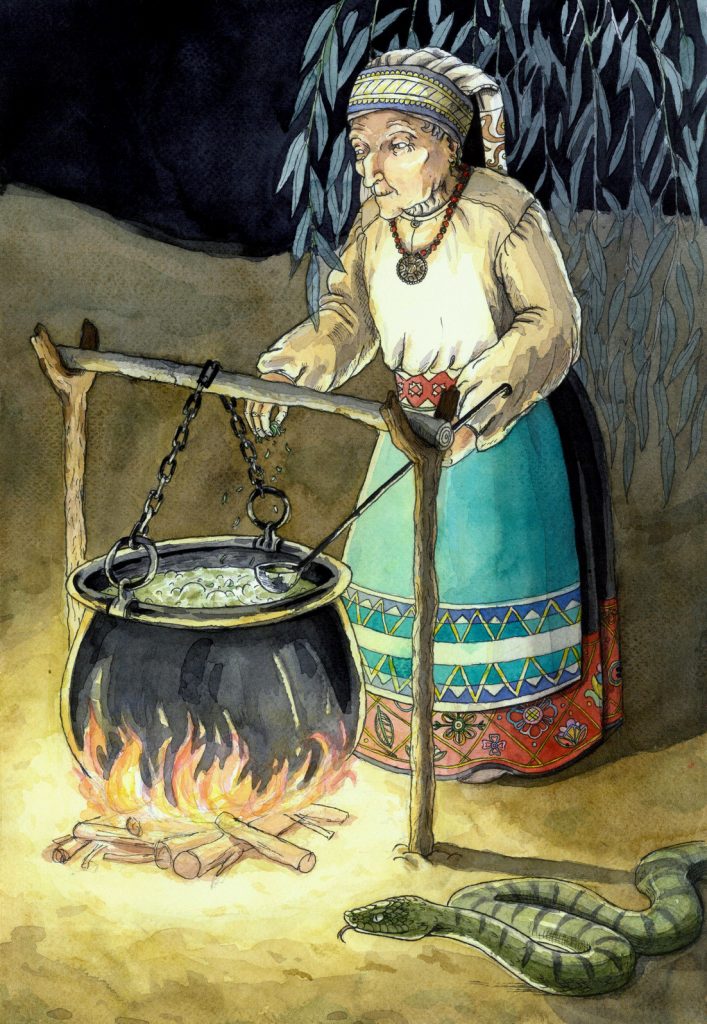

I bought some books about the Estonian traditional clothes, motifs and decorative patterns, to draw each detail out as accurately as possible. My aim was to be faithful to the Estonian meaning of the story, so I wanted to respect the symbolism and every element as carefully as it deserved.

I was so motivated that I wanted to read the Estonian original version, so I started to study Estonian on my own. For different reasons, I gave up, however. I was conscious about how difficult it was to learn, and it was hard enough to find all the information and illustrate such an ambitious project in so little time. So, in the end, I read an English version, which was hard to find, by the way.

Did you find it easy to come up with images?

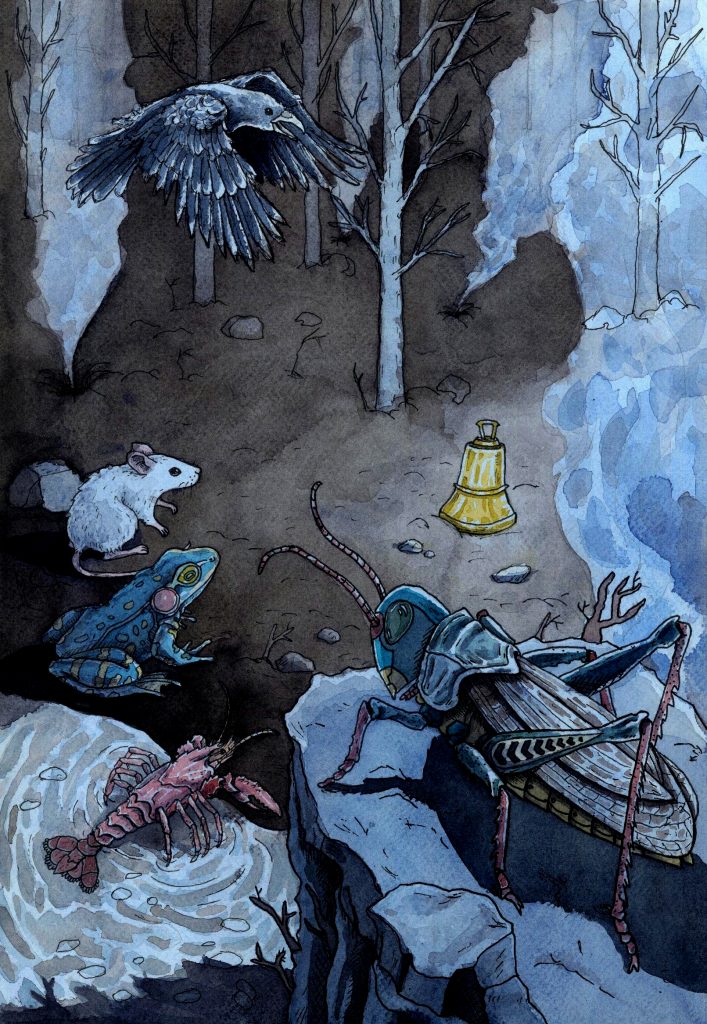

It was very strange, because at the end of each chapter, I very naturally imagined the relevant picture. It was like a vision of how I should do it and there wasn’t other right way – it just appeared spontaneously in my mind, inspired by the story.

I tried to capture that essence in each illustration, always demanding more of myself. I felt very comfortable and expressive with the watercolour technique and I was progressing every day. I wanted to improve and by each illustration, I tried to risk more – to challenge myself, to know my limits, but at the same time, discovering how far could I go.

What did you learn from the epic and do you have something similar in Spain?

Kalevipoeg was very inspiring for me, it taught me a lot of values about friendship, respect for the nature, altruistic help, courage and effort. While reading it I was really “transported” in the adventure. Thanks to Kalevipoeg, I could also discover more about the Estonian plants and animals.

In Spanish culture, maybe we could compare it to the “Cantar de Mio Cid” o “Tirant lo Blanch” in Valencia – both epic medieval stories, although they are far from the meaning of Kalevipoeg.

How do you think the Spanish would appreciate your work – would they understand it?

At the exhibition in the Museu de la Festa d’Algemesí (Valencia), the public was really curious about it and liked my interpretation. They were very interested about the story and thrilled with the topic; it seemed very exotic and mysterious.

Also, I played a melody on the kannel (an Estonian plucked string instrument – editor) and they really enjoyed the relaxing and calm sound of it. I think the kannel sound also represents the emotions of the poem, so it made the people understand at least the feeling behind it.

How much is generally known about Estonia in Spain?

Unfortunately, very few people even know where Estonia is – there is very little information about the Baltics here and a lot of clichés in general about the northern countries. Hopefully, with my work, I can show a bit more about Estonian culture.

What are your future plans with your illustrations of Kalevipoeg? Do you want to carry on with illustrations related to Estonia?

I wish my illustrations could be published, it would be a dream I hope to fulfil. Also, I’d like to keep moving my Kalevipoeg exhibition to other places in Spain and hopefully some day in Estonia.

The national epic

In ancient Estonia, there was an oral tradition of legends explaining the origin of the world. A malevolent giant by the name of Kalev, Kalevine, Kalevipoiss, Kalevine posikine and Kalevin Poika, battling with other giants or enemies of the nation, appeared within the old Estonian folklore.

The early written references are found in Leyen Spiegel (a two-volume book of sermons, with parallel texts in Estonian and German, published in Tallinn in 1641 and 1649; it is one of the oldest complete Estonian-language books to survive) in 1641 as “Kalliweh”, and in a list of deities published by Mikael Agricola (the de facto founder of literary Finnish) in 1551 as “Caleuanpoiat”.

In 1839, Friedrich Robert Faehlmann, an Estonian who grew up in a Baltic German family, read a paper at the Learned Estonian Society about the legends of Kalevipoeg and subsequently sketched the plot of a national romantic epic poem. In 1850, after Faehlmann’s death, the Estonian writer, Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald, started to write the poem, interpreting it as the reconstruction of an obsolete oral epic. He collected oral stories and wove them together into a unified whole.

The first version of Kalevipoeg (1853) could not be printed due to censorship. The second, thoroughly revised version, was published in sequels as an academic publication by the Learned Estonian Society in 1857–1861. In 1862, the third version, printed in Finland, became finally available for everyone.

You can follow Joan Llopis Doménech on Facebook and Instagram.

All images by Joan Llopis Doménech.