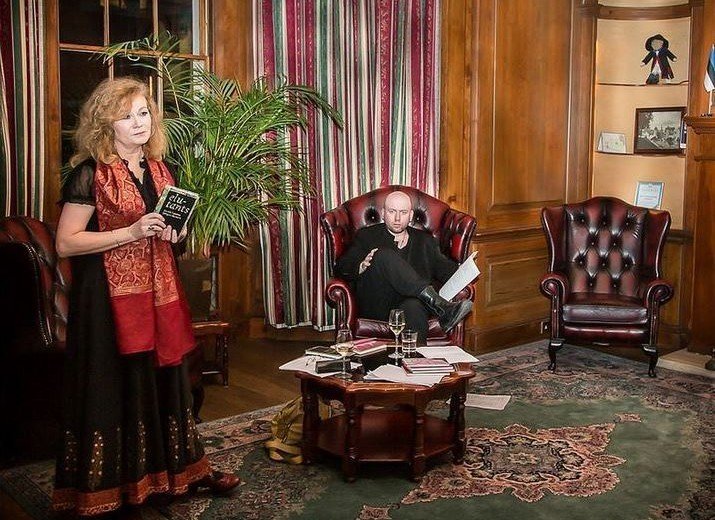

Doris Kareva has been writing poetry since the 1960s and her numerous books have won acclaim in Estonia and beyond. Kareva‘s poetry has been translated into over 18 languages, making her one of Estonia’s most internationally prominent poets. Her poetry is highly personal, yet speaks to universal themes connecting the human experience with nature and metaphysics. In addition to writing poetry, Kareva is an experienced translator, helping to bring more Estonian poetry to the attention of the wider world. Kareva regularly reads her poems at literary festivals throughout the globe. In January Doris appeared with Estonian poet Jürgen Rooste for a poetry reading at the Estonian Embassy in London. Kareva and Rooste have spent the last two years collaborating on the poetry project Dance of Life. Dance of Life’s poems have been set to music and the album, complete with the text of the poems, is released globally this month. I recently asked Kareva about her approach to poetry and she was good enough to answer some questions.

Would you consider your poetry idealistic or pessimistic?

Never thought in those terms. Traces of both can probably be found here or there in my writing – just like in passing moods of most people. Like every cloud has a silver lining, every idealist, in return, faces a moment of pessimism now and then, but never loses hope.

Elements of nature frequently occur as themes in your poems. Is interaction with nature an important part of your life?

Just natural. I would not, however, consider myself a so-called nature poet; speaking about, say, the sea or sky or stone I usually refer to what is universal. Born in Tallinn, where I am still living, and not having even a summer house like most Estonians do, I don’t have any Rousseauian urges of getting back to nature, because I never have felt any division. But yes, interaction with nature is very important for being human.

How would you define the spiritual aspect of your poetry?

Defining is something I would rather leave to others. For me, reading or writing poetry at its best is a somewhat mystical, transcending experience. Like Emily Dickinson said: “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way?”

If you didn’t write poetry how would you like to express yourself?

Jewellery could be one opportunity; the art of bringing out the amazing beauty of natural stones, pearls, seashells etc. I am often enraptured by some word combination just as if I had found a glowing piece of amber from sand or the colourful feather of a rare bird. But maybe even more I would like to become a real storyteller. True, I have published a book of tales, not for children, but for all ages, yet I feel I am still at the beginning. There are hidden stories in everything, everywhere, whispering to those who are willing to hear – and who can recognise the eternal wisdom in them. But often life is too loud, too demanding and impatient to let one slip into this dreamlike state long enough for stories to appear.

Your poetry has been translated into several languages. Beyond this are there any other cultures that you would think might respond well to your poetry?

My Hindi, Kannada and Bengali translators have referred to some other Indian languages that may render my texts even better. This is what I can’t tell. But languages which have preserved their ancient roots are probably closer to understanding my texts and easier to be translated into. Usually I avoid contemporary words; they have no power. Being invented, not born, they carry only the information, not containing magic of their own.

Maybe this is rooted in my childhood, when I created my own mental universe with many gods and special rituals to turn to them – writing a letter on a small piece of paper, tearing it into even smaller pieces and letting go with the wind. To be heard, one had to be sparse with words and choose only those worthy of gods.

Do you enjoy having your poems set to music?

Sometimes, yes, very much so. My father Hillar Kareva was a composer and he often complained that my original texts are so dense with inner music there is little room for adding any. However, I have written some texts specially for him as well as for some other Estonian composers. And quite a few British, Swedish, Flemish, Dutch, Greek, Thai etc composers have set music on translations of my poems. Some pieces of those are really awesome. For example, “Dance of Life” was written together with Jürgen Rooste, for Tallinn Mass composed by Roxanna Panufnik. I was deeply impressed by Roxanna’s inspirational way of melting together fragments of Estonian folk songs, sounds of Tallinn church bells and texts from “Dance of Life”, sung beautifully by Patricia Rosario and read by Jaak Johanson.

I also have much enjoyed the concerts together with Swedish or Dutch musicians, them playing and singing in their language, with me reading the original texts in Estonian. The recent concert tours with composer and jazz pianist Stefan Forssén and the vocal string quartet STRÅF have been a delightful experience.

I am quite pleased that my poems have been performed by very different musicians, from punk bands to a male choir at the funeral of the late President Lennart Meri. But I am not necessarily thrilled or flattered by the mere fact that someone has found a poem of mine usable. So it mostly depends on the music.

Do you think Estonians value poetry more than other European cultures?

Estonians are painfully aware of the possibility of losing their language and their identity. For this reason maybe poetry in Estonia is meaningful not only for a selected few, but for a larger audience. Some poetry books are selling tens thousands of copies. But basically, the amazing rule of thumb that became evident at the first European Poetry Forum in Helsinki is that no matter the population, the amount of poetry readers is tiny in all European countries. It is just the percentage of the whole population that gives Estonia special credits.

Is writing poetry a joyful process or a difficult process?

There is no contradiction. Comparison with giving birth may be a cliché, but the elements of almost painful concentration and overwhelming ecstasy are certainly present. And sometimes, what turns out to be poetry, just happens; it is given to you like a dream. So, always keep your heart alert and your pencil at hand.

I

* I dreamed about the world (by Doris Kareva)

That wild one,

it attempted to surround me, and to match

the shores of my imagination.

No,

I whispered, I’m in search of something else —

the unexpected,

endless as the universe —

a new,

refreshing, melted way of being.

Oh world, be bigger, please!

I asked.

And so it was;

the answer that was given

crushed me;

I was blinded by the light

and an explosion from the bottom of the world

broke up each layer of my hopes,

the hot transformed me

out of recognition.

Alone to soul and trembling, naked,

I woke up —

the stars were falling.

Reached out my hand, afraid and passionate.

And burst to laughter,

twigging to the dream

I had about the world —

the dream of love;

the dream.

I

Cover photo: Doris Kareva presenting Dance of Life at the Estonian Embassy in London (Kaido Vainomaa).

* Copyright: Estonian Literature Centre.