Estonia’s most famous children’s programme, Mõmmi ja aabits, has achieved the sort of international recognition it never set out to win: a place on American humour site Cracked’s list of the “7 Most Accidentally Horrifying Children’s Characters”.

For decades, the show was a national institution. First aired live in 1973, it was based on Heljo Mänd’s 1971 story Karu aabits (The Bear’s Primer) and followed a bear cub learning his ABCs. By 1976, 17 episodes had been produced, though none survive. A colour remake appeared in the late 1970s, with further sequels and a 1990s revival. Director Kaarel Kilvet often underlined its mission: to combine literacy with lessons in kindness and family values.

Mõmmi sings, children shiver.

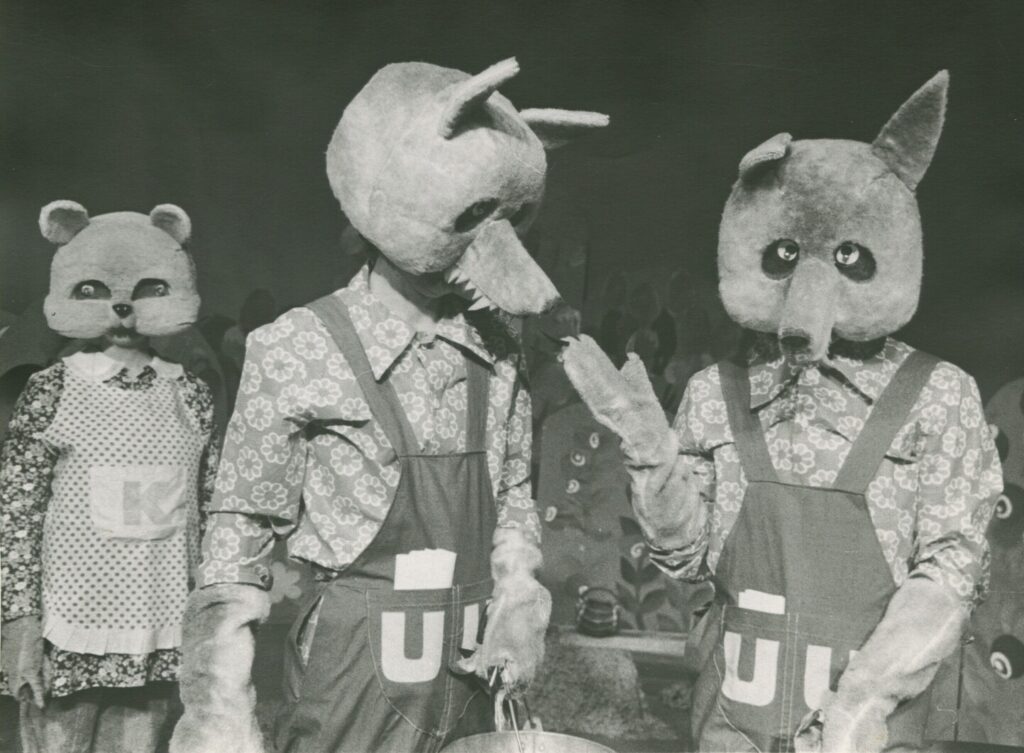

Cracked saw something else. What unsettled its writers – and, truth be told, many Estonian children at the time – was the design of the costumes. The actors wore half-masks perched on their heads, leaving their human mouths fully visible beneath painted snouts.

“It’s like A. A. Milne anthropomorphised a bear, but forgot to subtract its all-consuming lust for flesh,” the site declared. The blank glass eyes didn’t help: “dead orbs filled with liquid hate.” The result, they concluded, was “serial killers wearing the skins of adorable animals … a Hundred Acre Wood wherein Christopher Robin has been replaced by a young John Wayne Gacy (an American serial killer – editor). Oh, bother.”

Murder Bear’s morning brew: dark, strong and slightly unsettling.

Strictly Come Terrifying.

Mõmmi’s new global reputation places him alongside an eclectic gallery of childhood trauma. Japan contributed Fukurokuju, a puppet-headed god with, as Cracked put it, “a wrinkly dong for a head”. Britain’s entry was Mr Noseybonk, described as the unholy spawn of “Mr Bean and Jigsaw”. Switzerland’s avant-garde troupe Mummenschanz were remembered for building faces from clay like “a Hellraiser outtake”, while Czechoslovakia’s giant twitching bedsheet Ratafak Plachta was framed as a Soviet attempt to weaponise nightmares.

Australia added Lift Off’s faceless toy EC (good luck sleeping), and Sweden contributed Biss och Kajs – or, more directly, Piss and Shit – who spent their time demonstrating bodily functions on screen.

By comparison, Mõmmi almost looks tame. Still, generations of Estonian children who sat through his fixed snout and disturbingly human mouth might not be surprised that outsiders find him less Winnie-the-Pooh and more Winnie-the-Pooh-in-your-cupboard. Proof, perhaps, that even the most earnest educational television can, decades later, double as nightmare fuel.