Abja-Paluoja, the capital of Estonia’s historic Mulgimaa region, has become the Finno-Ugric Capital of Culture 2021; Adam Rang, who is currently writing a book about Estonian sauna culture and its origins among Finno-Ugric peoples, attended the ceremony and reports on why it matters.

It had all the grandeur, if not the scale, of a major diplomatic gathering. There were presidents and senior politicians, rows of flags, international guests, television cameras and translators providing live commentary for audiences tuning in from around the world.

The location was the quiet south Estonian town of Abja-Paluoja where, on Saturday, 13 February, around 100 people gathered in freezing temperatures proudly wearing their folk dress to witness the town receive the title of the Finno-Ugric Capital of Culture 2021.

Abja-Paluoja is the capital of Estonia’s historic Mulgimaa region whose residents, known as Mulks, have their own distinctive Mulgi dialect and culture. The first Estonian-owned farms were developed here from the early 19th century and, as a result, it was once one of the wealthiest parts of Estonia. The Mulk men are iconically depicted wearing long black robes.

During the ceremony, a symbolic wooden bird, known as the Tsirk, was handed over to the town. It was then paraded through the streets and placed in the window of a local bookshop. Each of its feathers represent a Finno-Ugric nation and its wings are spread as if about to take flight in order to represent the hope for their future.

The Finno-Ugric languages are notoriously tricky to learn

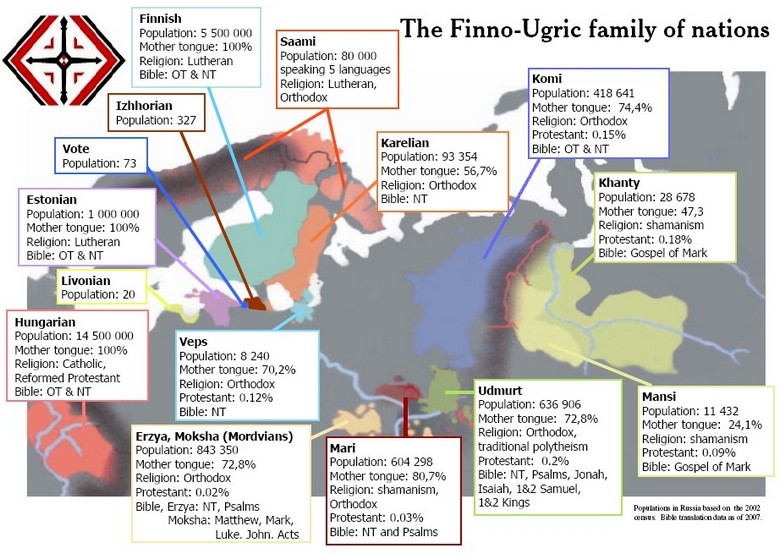

The Finno-Ugric world comprises 25 million people who mostly live in north-east Europe across the Nordic and Baltic regions and Russia.

While 95% of Europeans speak a mother tongue from the Indo-European language family, like this one you are currently reading, the Finno-Ugric language family – to which Estonian belongs – has entirely separate roots. There is only one other surviving language family indigenous to Europe, which is the orphaned Basque language, whose relatives have long since disappeared, along with any other languages in Europe that predate the spread of Indo-European languages.

The Finno-Ugric languages reflect a worldview that is closer to nature and animals. They are also notoriously tricky to learn for speakers of Indo-European languages like English.

The Finno-Ugric people are descended from the Proto-Uralic people whose original homeland was somewhere among the Ural mountain range of what is now central Russia. One group that migrated away was known as the Proto-Finnic people or Baltic Finns, who settled on the Eastern shore of the Baltic Sea and eventually formed the Estonian and Finnish people. This process likely began about 6,000 years ago as this coincides with the arrival of what archaeologists call pit comb culture.

With the exception of Hungarians, the Finno-Ugric peoples have lived a precarious existence for most of the recorded history and their languages were treated as inferior on their own territory by their various overlords. In the early 18th century, for example, the number of Estonian speakers had dwindled to below 100,000, less than a tenth of what it is today, while their landowners spoke German and their rulers spoke Russian.

Yet, despite the odds of history, there are now three independent Finno-Ugric states – Estonia, Finland and Hungary. In total, though, there are generally thought to be 14 Finno-Ugric peoples, defined as having their own distinct language and cultural identity.

The others that have survived enjoy varying levels of regional autonomy and official recognition as minority languages, such as in Russia which is home to the third largest population of Finno-Ugric peoples. In addition, there is no clear consensus on the number of other identities that could be described as either regional dialects or separate languages.

A greater focus on preserving the local dialects

Even the language we now call Estonian was one of several dialects of Estonia. Before the Soviet occupation, language standardisation was considered essential for nation-building. This resulted in the standardisation of the north Estonian dialect spoken in Tallinn.

While preservation of the Estonian language remains a cornerstone of the Estonian state to this day, its policy towards dialects has been reversed since the restoration of independence. Dialects such as Mulgi are now officially encouraged and supported, including through local media, arts and schooling in local dialects.

Speaking during the ceremony, the Estonian president, Kersti Kaljulaid, said there should be even greater focus on the preservation of the local dialects, such as the Mulgi language. Võro and Seto have flourished most over recent years, the president noted, but she also hoped to see textbooks in all Estonian dialects. Kaljulaid also reminded those watching that Estonians at the UN have always stood up for the rights of indigenous peoples everywhere.

The former Estonian president – and local Mulgi resident – Toomas Hendrik Ilves also attended in his role as Patron of the Mulgi Institute. Ilves praised the survival of Finno-Ugric peoples, despite noting they have all been pressured by their larger neighbours to abandon their culture and language.

“I call upon all of us to make efforts to get to know our kin,” Ilves asked the attendees and those watching online. “Then we will feel more confident, more secure and stronger. Then we will have the knowledge that our languages and songs will sound for centuries.”

Estonia’s leading role

The idea of kinship among Finno-Ugric peoples is a relatively modern concept. The connection between the Hungarians and the Sámi was first discovered in the 18th century and it wasn’t until the 19th century that the Finno-Ugric language theory was properly developed and understood. Yet another Estonian president, the late Lennart Meri, also had a significant role as a historian in investigating and developing the popular understanding of the Finno-Ugric shared identity.

The Soviet Union, under Joseph Stalin’s rule, purged intelligentsia who were embracing the Finno-Ugric languages, and the state policy for the rest of the Soviet Union’s existence continued to repress the concept of distinct cultural identities, preferring a simplified narrative about the national peoples that it falsely claimed had willingly joined the Soviet Union.

Meri defied this policy by travelling into Russia to document the similarities among Finno-Ugric cultures. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia has also reversed its policy to officially embrace Finno-Ugric languages, although this policy exists more often on paper than in reality.

Many of the initiatives to support the Finno-Ugric peoples are genuine grassroots initiatives from across the Finnic-Ugric world, but Estonia has had a leading role in making them happen. The idea of a rotating cultural capital for the Finno-Ugric peoples was first established in 2013 by activists at MAFUN, the International Youth Association of Finno-Ugric Peoples. One of those activists, Oliver Loode, runs the URALIC Centre as an Otepää-based NGO with the mandate of coordinating the cultural capitals programme.

The Finno-Ugric World Congress will also take place this year in Estonia after being postponed last year due to the pandemic. President Kaljulaid’s invitation to the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, to attend remains open.

No unifying flag theme

Just as notable about the Finno-Ugric peoples is what they do not share in common. While Estonians share close genetic similarities with their Indo-European speaking neighbours, particularly in Latvia, the Finno-Ugric identity is a linguistic rather than an ethnic identity. Several Finno-Ugric attendees from Russia at the ceremony have an Asian appearance, despite their closeness in language and culture.

Lined up prestigious along the sides of the ceremony, it was also noticeable there was no unifying theme to the flags of the Finno-Ugric nations. Each one tells a different national story as it was created during national awakenings that took place under different circumstances.

The flags of Estonia and Hungary are tricolours. This flag design is rooted in the enlightenment movement and spread in popularity across Europe primarily through the revolutions of 1848, which were also known as the spring of nations. This influenced Estonian students whose student society flag later became the national flag of Estonia. Finland’s flag clearly conveys its Nordic association, while others depict various cultural motifs and patterns.

Neither Hungary nor Finland treat the Finno-Ugric identity with quite as much reverence as Estonia, which has a stronger understanding of the fragility of nationhood. It has even changed the law to celebrate the Tribal Day, also known as the Finno-Ugric Day, every October.

The benefits would be born in Mulgimaa

“Estonia takes a central role in Finno-Ugric unity,” Bogáta Timár from Hungary, who sang in Mulgi during the ceremony, said. Timár is studying for a PhD in Finno-Ugric studies and has lived in Estonia for a year. In her spare time, she’s a band member for a student music group called Kännu Peal Käbi, which performs songs in various Uralic languages.

“Estonia is basically the mother of the Finno-Ugric family in the sense that she takes care of everyone. Finland is the single aunt who’s usually too cool to care but occasionally expresses her opinion, while Hungary is the crazy uncle who moved to another continent and only shows up for Christmas.”

Estonia’s central role is helped by the fact that Estonia doesn’t feel too foreign to any other Finno-Ugric nation, Timár believes. It’s close enough to Finland, Russia and Hungary to feel familiar to all of them.

“Estonians enjoy this role,” adds Timár. “The Finno-Ugric world is a place where they can feel large and influential.”

Asked after the ceremony what benefits would be brought to the region through the Capital of Culture title, Kaljulaid explained the benefits would be born in Mulgimaa, not brought to Mulgimaa.

“The benefits can only be born here are the greater attention to the Mulgi language and Mulgi culture,” she said.

One speaker in the ceremony had to pause momentarily as the siren of an ambulance passed by, a reminder of yet more challenging times in which we are living and which will prevent significant numbers of international visitors from taking part in any of the activities locally.

Yet the pandemic has also brought unexpected benefits to Estonia’s regions. Usually, 75% of international visitors remain in Tallinn, some only for a few hours after hopping off and back on a cruise ship. The pandemic has led to a surge in domestic tourism instead and Estonian tourists are more likely to spread out across the country in search of authentic experiences that support local businesses.

The challenge for Mulgimaa will be to make the most of this opportunity now and sustain the focus on their culture and region when international visitors return in future.

A schedule of events throughout 2021 in English can be found on the Mulgimaa website.

Overlapping Estonian identities

While debates continue about Estonia’s modern identity, such as whether it is a Nordic country, Estonia’s embrace of its ancient Finno-Ugric heritage is more meaningful and reveals a more fundamental aspect of what it means to be Estonian. It also contradicts the common perception that Estonia is only interested in looking west or north in order to define its place in the world.

The Estonian state was forged most fundamentally out of a desire to ensure the continuation of the Estonian language, around which the Estonian identity and culture is based. Estonians understand the fragility of this more than most nations. By championing other Finno-Ugric and indigenous peoples, Estonians are reasserting their own right to survive and thrive. Their empathy is also sincere, as is their contempt for supranational rulers who would seek to prevent languages from flourishing.

This worldview is now being expanded to include the survival of all Estonian dialects. Language standardisation in the early republic partly reflected an anxiety to keep the nation together in its fledgling state. The promotion of dialects now reflects a greater confidence in the future of Estonia and an acceptance that overlapping identities can coexist.

Estonians can be Mulgi and Estonian. Just as they can be Nordic and Baltic, Western and Eastern, European and global. All these identities add up to what it means to be Estonian.

The Cultural Capital title didn’t have to be an important occasion. Thousands of cultural exchange initiatives like this are attempted continuously all over the world with little fanfare. They rarely attract senior politicians or media coverage. Yet Estonia chooses to use its power to support the wider Finno-Ugric family because it’s a key part of the story of Estonia.

A nation is ultimately a shared story and here it is one that will continue to be told in Estonian and its various dialects, such as Mulgi.

Cover: Mulgimaa takes centre stage as Estonia embraces its Finno-Ugric family. Photos by Taavi Bergmann.