The London Book Fair 2018 focussed on Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania as the countries are celebrating their centenaries; numerous events at the fair concentrated on Estonian books, writers and translators in the city that is considered a gateway to the European markets.

The London Book Fair, held from 10-12 April 2018, is over. It has always been an event for discovering opportunities, to do face-to-face business. This year, over 25,000 delegates from 130 countries participated, over 200 professional events like panel discussions, seminars and training sessions took place. Traditionally, it is a showcase for individual publishing markets, where contacts are made and deals are done.

It was, no doubt, a great moment for Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – the countries that were focussed on at the global market place – and one may only hope that the grand event at Kensington Olympia will get transformed into a remarkable impact in the publishing industry of the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world. As several European publishers still consider London a gateway to the European markets, the impact might even be echoed on the continent. Perhaps even on several continents, one never knows; all we know is that in the modern world writers are as essential as a glass of water.

Audio books and non-fiction becoming popular

What is the news in a nutshell regarding the LBF 2018? It is the first time one notices such a remarkable growth in the use of audio books – especially among men in their twenties, thirties and forties. Also, the importance of poetry has grown – probably as a counter-reaction to politics. Blogs, literary blogs are getting more and more noticed. And no doubt, the book fair highlighted the interest in book illustration. According to statistics, children are remarkably good readers, so one can be sure that books have a great future; and not only traditional books but also e-books.

The popularity of non-fiction is growing fast; a good example being the huge pre-publication interest in “Meghan: A Hollywood Princess”, written by Andrew Morton. A generation ago, Morton’s book, “Diana: Her True Story”, was an explosive account on the princess’s conflicted secret life. The book on Meghan Markle involved a thorough research, on the basis of which the author claims that she is the person who has made the royal family relevant for the next 100 years.

Translations and translators are in the limelight, as are many cross-cultural and global topics. Brexit means insecurity for all those tens of thousands non-UK citizens who work in different sectors, including the publishing industry of the United Kingdom. Moreover, it may mean a shift from the traditional use of London as the publishing markets’ gateway to Europe.

Translators turn into writers

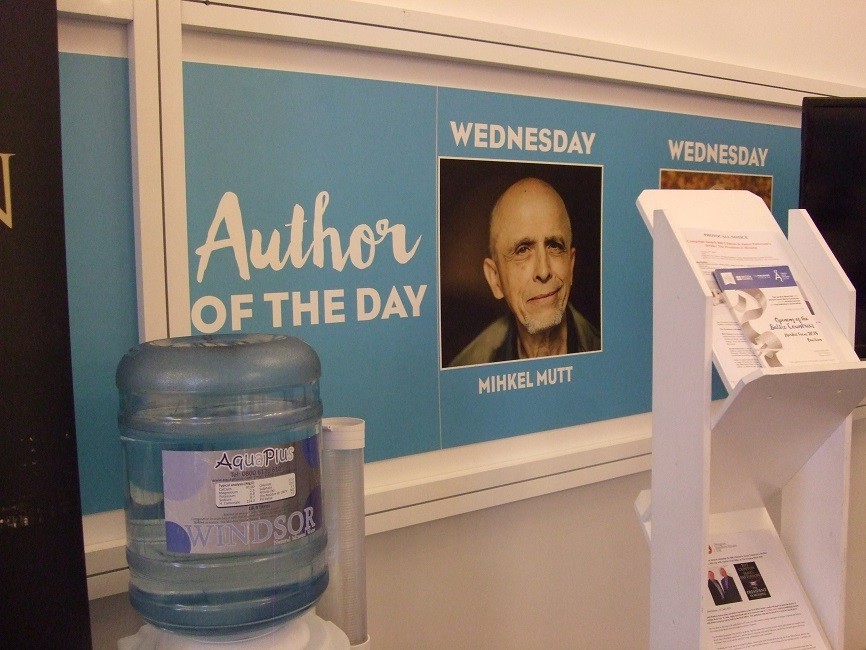

But back to the translators, and also the translators turned into writers. The latter may have a great future due to their obvious capability of presenting their texts in a more accessible manner for readers of the global village. The panel discussion during which Maarja Kangro (who explained that she was a translator who grew into being a writer), and Christopher Moseley (who has translated several Estonian authors into English) teamed up on the topic was utterly intriguing and most enjoyable.

Be it a box of Malta, a display area of Estonia or display areas of China, translators were given a voice. Miriam McIlfatrick, Susan Wilson, Adam Cullen, and Christopher Moseley – experienced and creative translators from Estonian into English – were seen taking part in different events of the book fair. Be it Estonia or the UK, publishers are interested in getting good translations from the translators who have developed a cross-cultural grasp and perfect language skills.

Over the years, the Estonian Literature Centre, headed by Ilvi Liive in Tallinn, has made a remarkable effort to train those who translate Estonian books into foreign languages. It is not an exaggeration to say that among many other things, the Estonian Literature Centre has managed creating a global network of professional translators.

The other side of the same coin is translating from foreign languages into Estonian. Interestingly, the topic drew a remarkably wide audience at a busy hour of the book fair. The translator and publisher, Krista Kaer, and the publisher, Christopher MacLehose, were in a gripping conversation that painted an intriguing cross-cultural picture of the history of translating into Estonian. By the questions and answers time, Christopher Moseley joined in, and the jostling of cameramen around them was swiftly followed by several one-to-one filmed interviews.

Moseley translates fiction not only from Estonian into English but also from Latvian, Finnish and Scandinavian languages – and somewhat surprisingly, even from Livonian. He teaches at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London, and for those English speakers who have studied Estonian, his name is familiar thanks to the complete course, “Colloquial Estonian” – the most popular text book written by him for learners of the Estonian language.

The most recent good news is that on top of grammar, from 2018 it will be possible to study under his supervision an undergraduate course introducing the literature of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in English translation.

The list of Estonian writers Moseley has translated is impressive, including Andrus Kivirähk, Indrek Hargla, Maimu Berg, Anton Hansen Tammsaare and even Ene Mihkelson, whose “Plague Grave” is a remarkable challenge for the most experienced translator (a chapter of the book is available in the Riveter magazine, Riveting Baltics Writing, April 2018).

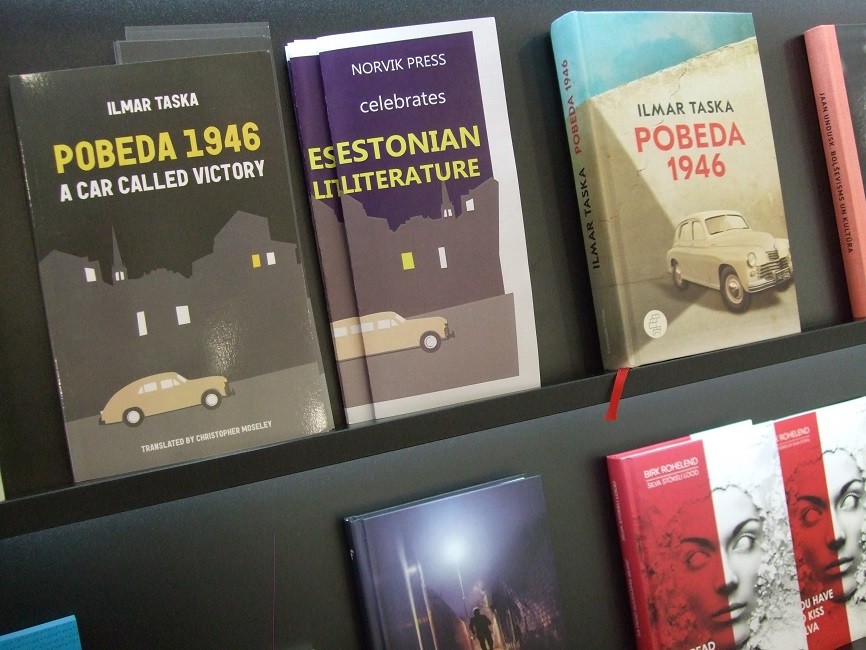

Moseley’s most recent translation of a novel is “Pobeda 1946: A Car Called Victory”, written by Ilmar Taska – the book that has just been published by Norvik Press and is now available for the readers living in the United Kingdom.

Problems reflected in the Taska’s book as relevant as ever

“Pobeda 1946: A Car Called Victory” is Taska’s first novel. Published by Varrak in 2016, it has already been translated into Finnish, Lithuanian, German and Danish, and enjoys both critical success and popularity among readers in the respective countries. Taska is a modern and sensitive author with a remarkably visual style of writing. His career started in the TV and movie industries: he has worked at Tallinnfilm, the Swedish television and Hollywood film companies.

Compared with many authors, Taska’s grasp is global; however, while reading this book, one realises quickly that it is a very personal story – Taska was born into a family that had been deported to Kirov.

Taska’s novel is based on characters turned into archetypes; from victims to the new era collaborators, each character gets a voice in the light of the power change that impacted the lives of people in occupied Estonia. Moreover, each character has his or her hopes stemming from their perception of the changing world; and when the hope dies, the voice certainly dies.

As the book has been published only recently, the conversation between Taska and Rosie Goldsmith (the director of the European Literature Network and a former BBC journalist) that took place in the framework of EstLitFest was keenly followed by would-be readers.

Taska cleverly draws a line between collective and individual: on the one hand, there are people who have lost their names in the narration – the main characters are “the woman”, her son who is just “the boy”, and a KGB man who is “the man”; on the other hand, there are those who still have their names, the two striking individuals – Johanna, an Estonian opera singer and Alan, a London-based BBC news director – whose love story stamps the book with great hope. Having said that, I must admit that there stays a nagging question regarding “the boy” – will he become “the man”?

Johanna’s problems are in many ways the problems reflected on by Sofi Oksanen in “When the Doves Disappeared” and by Margaret Atwood in “The Handmaid’s Tale”. Will the woman who succeeds escaping the totalitarian world be understood in the free world? Will the door behind her be locked forever? And just to think of all those many other questions following the first two.

The problems reflected on in the Taska’s book are as relevant as ever; the wartime is not the past. The picture he paints of news production, and the way readers are led to follow Johanna in order to discover the real news within the news is pretty amusing. It reminds one of a Russian doll, and maybe brings to mind people discovering messages left by famous tailors into the suits and dresses worn by their famous clients. Date of arrival is often depending on the mind-set and resourcefulness of the recipient.

Finally, I hope my reader will forgive me for not having been capable of shedding light on so many other truly interesting events that took place in the framework of the ever-vibrant London Book Fair. I do believe seeing is believing, and I hope to see it all continued next year, at the London Book Fair 2019.

I

Cover: London Book Fair 2018 at Kensington Olympia (credit: LBF). All images by Ann Alari except where stated.