The Baltic Sea is coming back to life and there is no need to stop eating fish, according to an Estonian scientist, Joonas Plaan.

This article is published in collaboration with Research in Estonia.

If we cared enough about our planet, we should all give up eating fish. This was the overall message in the world-famous Netflix documentary “Seaspiracy” that made waves in March 2021. This American movie showed how big fishing companies scraped the ocean floor with giant football stadium-sized nets and dump them afterwards, polluting the waters, and how bycatch and overfishing destroys marine wildlife. To stop the massacre, the authors proposed we should all stop eating fish in hope that the reduced demand will pull the industry back.

But the picture they painted only represents the poorest and the most corrupt parts of the world.

“While the documentary highlighted an important topic – the state of our waters – it doesn’t reflect on what is happening in our region,” Joonas Plaan, an Estonian fish expert and a lecturer of environmental anthropology at Tallinn University, said.

Eating small fish good for the Baltic Sea

In fact, the opposite is true. In the Baltic Sea, an arm of the Atlantic Ocean, squeezed between the Northern European countries, some fish should be eaten.

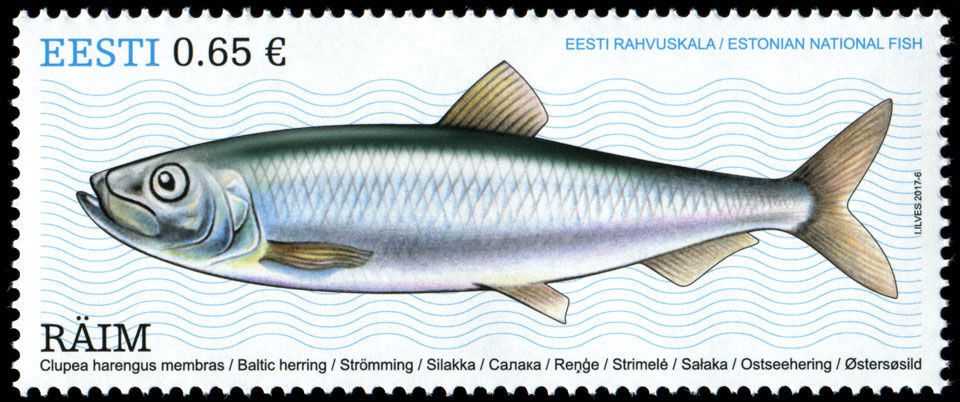

“Eating small fish benefits the Baltic Sea!” Plaan said. “It helps take the nutrients out of the sea.” The biggest problem in this North European sea is actually eutrophication – a process where the water is filled with minerals and nutrients. The main blame for this can be laid on the fertilizer-dependent agricultural industry that releases nitrogen and phosphorus into the sea. Should we stop eating bread and vegetables instead?

Plaan has a simpler recommendation: eat local fish, especially the little ones at the end of the food chain like Baltic herring and sprat.

“Round goby, ide, carp-bream, Prussian carp and white bream are also in abundance, even though they rarely end up on our dinner table,” Plaan said. Over the past decades, the numbers of these small fish have grown due to increasing temperatures and nutrients.

Larger fish endangered

At the same time, some of the larger predatory fish are endangered. Cod is at critically low levels in the Baltic Sea, and the numbers of perch, pike perch and plaice are dropping.

Each year, Plaan looks through large databases to evaluate the state of different fish in Estonian waters. Based on these numbers, he publishes his recommendations in the WWF Fish Guide on which fish is safe to eat and which not.

This year’s guide was published on 27 May and is meant for anyone interested in eating and catching fish in a planet-friendly way.

Plaan’s WWF guide recommends staying away from fish that are brought in from faraway places and where the conditions are not known.

Europeans love fish. An average EU citizen eats four kilograms (8.8 lbs) more fish or seafood than the rest of the world. The favourites are tuna, cod and salmon.

Most salmon, however, is grown in fish farms that have a list of problems. Among others, there are concerns about levels of antibiotics, pesticides and heavy metals in farmed salmon. Therefore, Plaan’s recommendation is to limit the intake of salmon to special days.

He also recommends not buying canned tuna if possible. “We don’t usually know how they have been caught,” Plaan explained. “Even if there are certificates on the labels that give information about the fish, there aren’t any guarantees. Eating locally is best for the environment and for us too because it makes us eat seasonally.”

The Baltic Sea is recovering

Even though it is seeing the impacts of climate change, the Baltic Sea is actually recovering, largely because the devastating Soviet practices ended three decades ago when the union collapsed.

The Soviet forces that once occupied Estonia, brought harmful industries with them that also heavily damaged the ecosystem in the Baltic Sea. “The Soviet period was a sad era for the Baltic Sea,” Plaan said. “There was a lot of overfishing.”

The fishermen were expected to fish as much as possible and were told to eliminate the fish-eating seals. During the 20th century, hunting reduced Baltic seal populations by 90–95%. “It was a massacre!” Plaan said. Even though they are now under protection – and the grey seal population has recovered – many fishermen still see seals as their enemies who eat their income and damage gear.

When the Soviet regime finally collapsed, giant trawlers that used to dock in Tallinn disappeared. In fact, bottom trawling – the most harmful way of fishing – is not used in most of the Baltic Sea – except for Western cod, caught by Danish, Polish, German and Swedish bottom trawling vessels. For now, this is the only way to catch some of the species that live at the bottom of the sea.

“Everything is marked down in the Baltic Sea,” Kaire Märtin, an expert of fishery resources at the Estonian environment ministry, said. The fish catches are highly regulated and inspected, even though grey areas remain. The amendments to the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy intend to improve operational and real time control and monitoring, making use of electronic log-books and GPS surveillance also in small-scale fisheries.

“The ecosystem in the Baltic Sea is changing and some fish are being replaced by others, but overall, things are getting better, even if not as fast as we would like to,” Plaan said, optimistically. “Environmental organisations and scientists are increasingly listened to, the collaboration with state officials is getting better.”

Bringing big shops on board

Scientists alone cannot make this change. Ultimately, it’s down to the consumers. Plaan regularly speaks to different retail chains to raise awareness on sustainable fish consumption. Rimi, one of the biggest retail operators in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, agreed to remove all the non-responsive and non-sustainable fish from their shelves in all the Baltic states.

Katrin Bats, Rimi’s public relations and sustainability manager in Estonia, said they closely follow the Estonian Nature Fund‘s recommendations. They now only sell sustainable fish on their shelves.

“This step forced our suppliers to change their products too,” Bats said. “Big chains like Rimi can really make an impact in the whole market and change the customers’ behaviour.”

After a year, she can draw the conclusion that the switch to a more sustainable selection of seafood didn’t change the turnover. Bats also hasn’t heard any complaints from the customers.

Clever solutions for sustainable fishing

“Estonia is standing out in many ways when it comes to sea life protection,” Kaire Märtin from the Estonian environment ministry said. Things can be changed fast and data collected seamlessly, which, in return, helps to make science-based decisions for more accurate state rules.

One example is an online application system for anyone who would like to apply for a fishing permit for angling or recreational fishing. No need to queue up or wait for hours. It only takes a minute and helps the government document and monitor what is going on in our waters.

Estonia is also fiercely fighting to open up the rivers to create better conditions for fish. When the rivers are clogged, it can be harmful for the whole ecosystem. To reverse the situation and restore biodiversity, discussions are taking place with different hydroelectricity power stations that have destroyed or significantly reduced migratory fish populations.

There is very clear and accessible knowledge about which food is sustainable and which comes at an unnecessary cost to the environment. As consumers, we should simply listen to the scientists.

Cover: A small locally caught fish cooked in Muhu island, Estonia. Photo by Oliver Moosus.