Estonian scientists from the Tartu Observatory, together with the scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and other partners, are preparing a set of three space missions to Venus to search for signs of life in the planet’s atmosphere.

According to a statement by the University of Tartu that owns the observatory, the scientists are in a consortium of scientific institutions and private companies in the effort; the project is expected to conclude with a return of samples from the Venusian atmosphere to the earth.

The goal of the Venus Life Finder missions is to assess the habitability of Venusian clouds and later to look for life in them, according to the university. The overall program is led by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

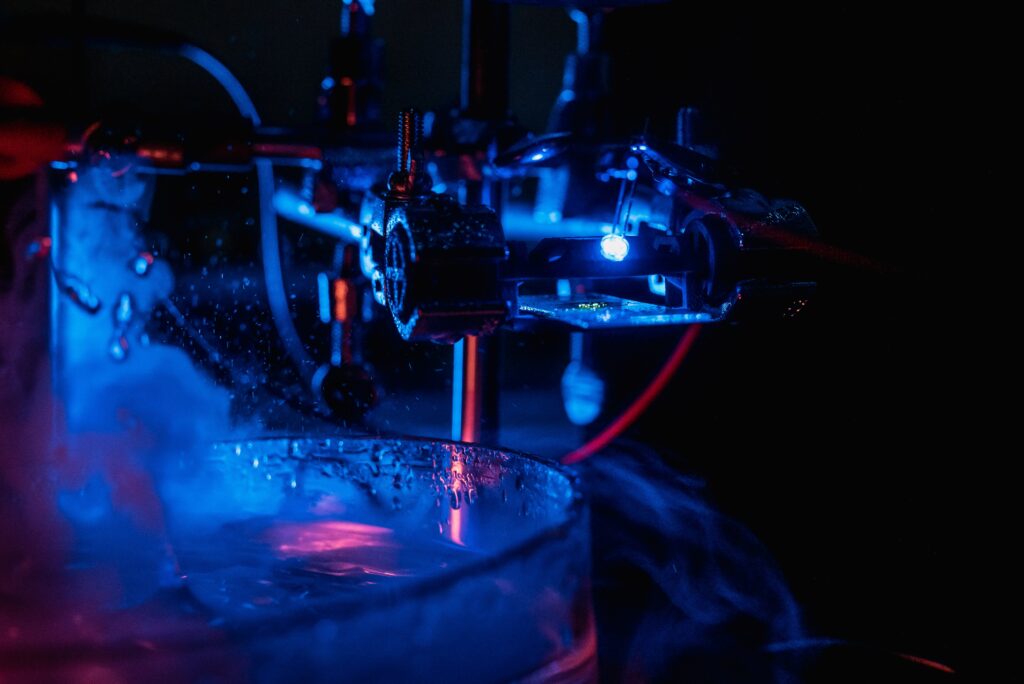

The university said in a statement that the scientists from the Tartu Observatory proposed two instruments for the Venus Life Finder missions, one for measuring the acidity of the Venusian clouds and one for measuring atmospheric oxygen. “A proof of concept for the acidity sensor was completed in 2021 as a part of the VLF mission study,” it added, using an acronym for the Venus Life Finder.

The Estonian Venus Life Finder team is led by the head of the Space Technology Department at the Tartu Observatory and associate professor in space technology, Mihkel Pajusalu. According to him, the current assumption has been that Venusian clouds are too acidic for life to exist there.

NASA and ESA aren’t looking for life on Venus

“New modeling efforts have shown that the existing data about Venus also agrees with acidity levels that some organisms on Earth thrive in. To actually measure the acidity of individual cloud droplets, the MIT team turned to the Tartu Observatory team to build an instrument for it. A first proof-of-concept prototype was completed in the summer of 2021,” Pajusalu said.

Although the Venusian atmosphere was studied last in the 1980s, Pajusalu pointed out that Venus is becoming a very popular target within the Solar system again.

“Both NASA and ESA have confirmed new missions to Venus, but none of these are suitable for looking for life in the Venusian clouds and for determining their habitability in general. Our missions are also novel because of financing from the private sector and the missions are developed outside space agencies to develop them faster and more cost-effectively,” Pajusalu said, according to the university.

NASA is the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in the US; ESA is the European Space Agency in the European Union.

The preliminary study was mainly financed by the Breakthrough Foundation from the US and several private companies, foundations and other partners are involved in preparation for the missions.

“Developing a single probe would take decades in space agencies, but we are planning to send out three probes in little over 10 years with a much smaller budget and more innovative instruments than conducting this through space agencies would allow,” Pajusalu added.

“Venus has probably started as a planet very similar to the earth, but a very strong greenhouse effect elevated its surface temperature past what can be reasonably considered habitable. At the same time, the temperature and pressure in Venusian cloud layers are similar to the conditions on earth’s surface.”

Inconsistencies in our current understanding of Venus

“In 2020, signs of phosphine were detected in the Venusian atmosphere and no processes are known that could produce this gas in these quantities on Venus without life. The freshly published VLF mission study also lists many inconsistencies in our current understanding of Venus and mysteries found in the datasets from Venus,” according to the statement by the University of Tartu.

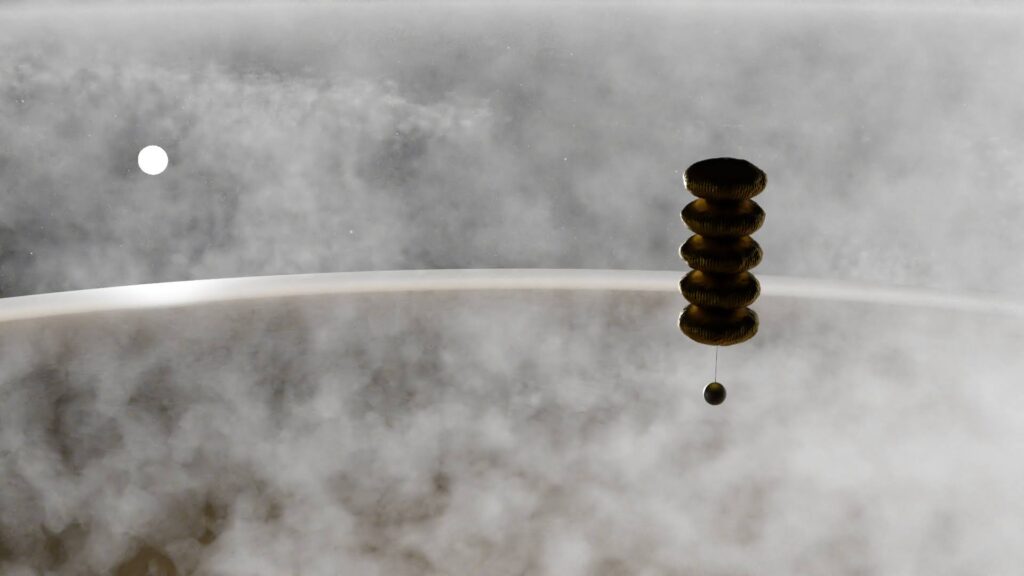

Venus Life Finder consists of three missions. First, in 2023, a Rocket Lab led mission will fly through the Venusian atmosphere and perform measurements to determine the shape and composition of the cloud droplets. In 2026, another mission is planned to deploy a balloon in the Venusian atmosphere and to perform more detailed and complicated measurements.

The instrument being developed in Estonia is planned on this probe. The third mission aims to return samples from the Venusian atmosphere for study on Earth, hopefully in the early 2030s, the university said.

The freshly published mission preliminary study involved over 50 scientists and engineers from the US, the UK, Poland, Japan, Switzerland and Estonia. The set of missions is led by professor Sara Seager from the MIT.

The Estonian participation in the preliminary study was by the Tartu Observatory team, led by the Head of the Space Technology Department at Tartu Observatory and associate professor of space technology Mihkel Pajusalu.

The other members of the Tartu Observatory team were Ida Rahu, Laila Kaasik and Iaroslav Iakubivskyi.

The Estonian acidity sensor going onboard the mission will be built by Estonian science institutions and private companies; its development is ongoing, the university said.

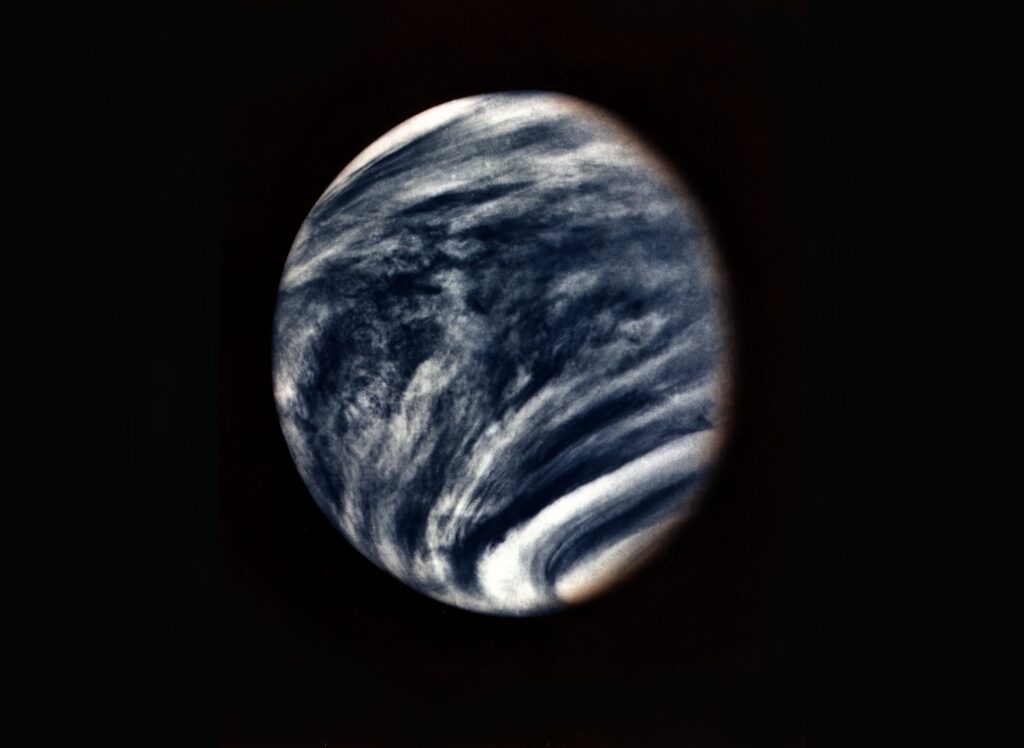

Cover: This picture of Venus was captured by the Mariner 10 spacecraft during its approach to the planet in early 1974. Photo by NASA on Unsplash.