The Federation of European Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning Associations, REHVA, has published a guidance on the operation and the use of building services in areas with a coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak.

This article is published in collaboration with Research in Estonia.

Representing a network of more than 120,000 engineers from 27 European countries, REHVA guidance complements the general guidance for employers provided by the World Health Organisation and is targeted to commercial and public buildings.

The document provides practical recommendations that cover ventilation system operation times, use of window airing, safe use of heat recovery sections, no use of recirculation in central ventilation systems as well as on the room level, and some explanation how to avoid overreactions that are easy to happen in situations with limited knowledge. Due to the ever-changing information about the disease, the document will be updated and complemented with new evidence when it becomes available.

“Our document addresses the risk of airborne transmission through small particles (<5 microns), which may stay airborne for hours and can be transported long distances,” Jarek Kurnitski, a professor at the Tallinn University of Technology and the chair of REHVA Research and Technology Committee, said. “Such small particles are generated by coughing and talking when larger droplets evaporate usually within milliseconds and desiccate. This mechanism implies that keeping a one-to-two-metre (3.2-6.4-foot) distance from infected people might not be enough and increasing the ventilation is useful because of removal of more particles. Infection risk can be high in crowded and poorly ventilated spaces.”

“The size of a coronavirus particle is 80-160 nanometres and it remains active at common indoor conditions up to three hours in indoor air and two-three days on room surfaces, explaining also another transmission route via surface (fomite) contact. Special risk is in toilets where flushing creates plumes containing droplets and droplet residue, therefore it is important to flush the toilets with closed lids,” Kurnitski said.

Increase ventilation and open windows

It is recommended to switch on ventilation systems a couple of hours earlier and to extend the operation. A better solution is to keep the ventilation on 24/7, possibly with lowered (but not switched off) ventilation rates when people are absent in order to remove virus particles out of the building. Exhaust ventilation systems of toilets should always be kept on 24/7, and make sure that negative air pressure is created, especially to avoid the faecal-oral transmission.

In buildings without mechanical ventilation systems, it is recommended to actively use operable windows so that one could open windows for 15 minutes when entering the room, especially when the room was occupied by others beforehand. Also, in buildings with mechanical ventilation, window airing can be used to further boost ventilation.

Opening windows in toilets should be avoided as this may cause a reverse direction operating ventilation and contaminated airflow from the toilet to other rooms.

Avoid air recirculation and turn off rotary heat exchangers

Recirculation should not be used, because virus particles in return ducts can re-enter a building in recirculation sectors of centralised air handling units. Thus, recirculation dampers must be closed via the Building Management System or manually. When possible, decentralised systems such as fan coil units that use local recirculation, also should be turned off to avoid resuspension of virus particles at room level.

Similarly to recirculation, heat recovery devices may carry over virus attached to particles from the exhaust air side to the supply air side. In rotary heat exchangers, particles deposit on the return air side of the heat exchanger surface after which they might be resuspended when heat exchanger turns to the supply air side. Therefore, it is recommended to (temporarily) turn off rotary heat exchangers during the coronavirus pandemic episodes.

Actions that have no practical effect

It is also important to understand which actions have no practical effect and are not needed. Transmission of some viruses in buildings can be limited by changing air temperatures and humidity levels.

In the case of the COVID-19, this is unfortunately not an option as the virus is quite resistant to environmental changes and is susceptible only for a very high relative humidity above 80% and a temperature above 30˚C (86˚F), which are not attainable and acceptable in buildings for other reasons (eg, thermal comfort). Thus, there is no need for humidification, and usually any adjustment of setpoints for heating or cooling systems is not needed.

Similarly, there is no need to replace outdoor air filters of the ventilation system, which are not a contamination source in this context. Room air cleaners can be useful in specific situations, but the floor area they can effectively serve is normally quite small, typically less than 10 square metres (108 square feet).

There have been overreactive statements recommending to clean ventilation ducts in order to avoid coronavirus transmission via ventilation systems. Duct cleaning is not effective against room-to-room infection because the ventilation system is not a contamination source if given guidance about heat recovery and recirculation is followed.

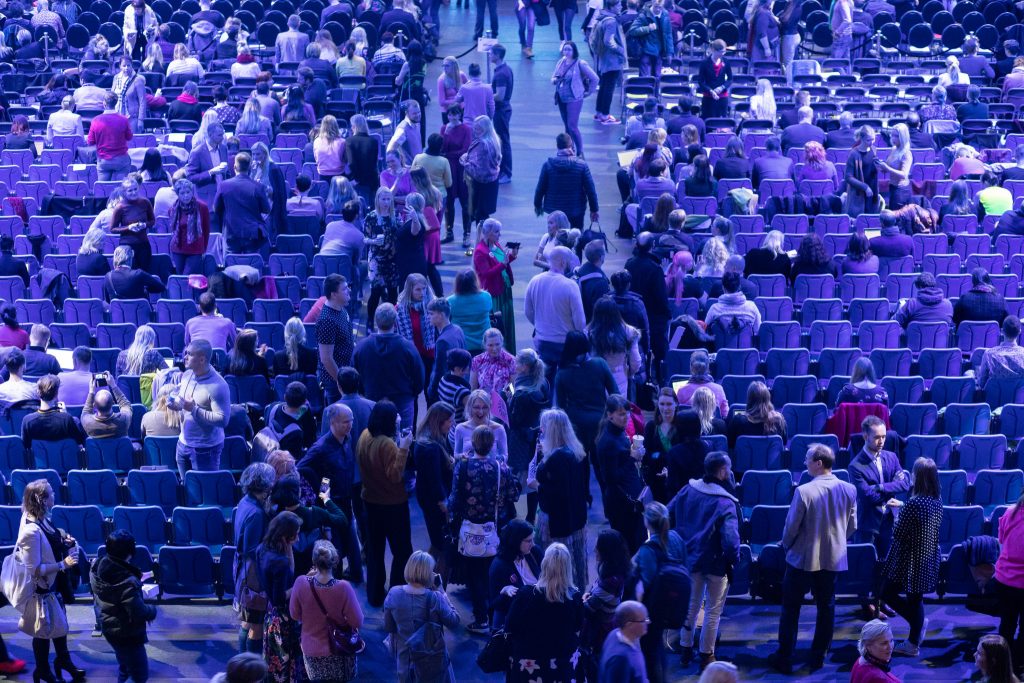

Cover: Camping in Estonia. The image is illustrative (photo by Katrina Tang).