A recent study carried out by an international group of building scientists showed that Estonia is among the countries with the most energy-efficient buildings in Europe.

This article is published in collaboration with Research in Estonia.

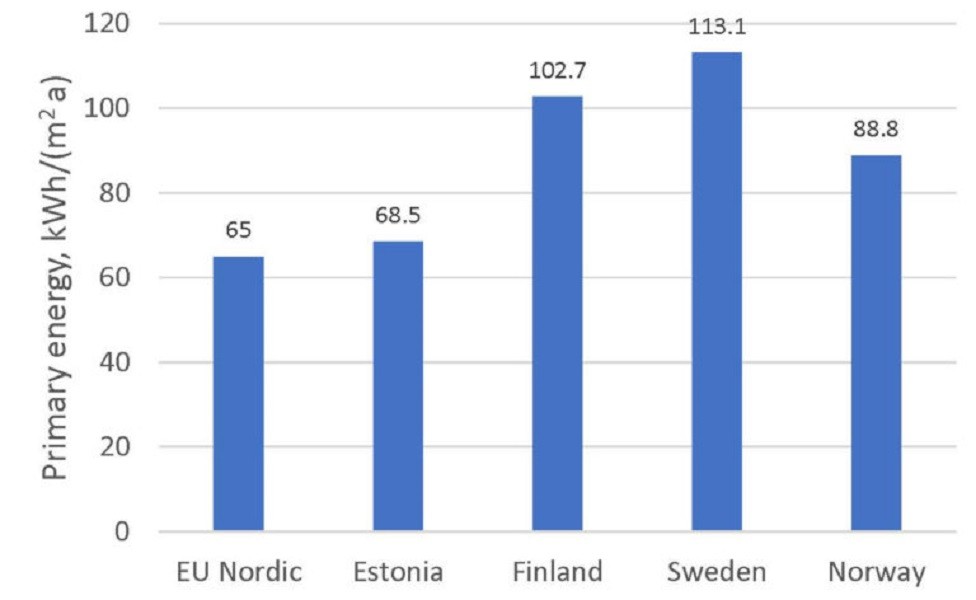

The analyses of the NZEB (nearly zero-energy buildings) energy performance requirements and reference apartment buildings in four countries – Estonia, Norway, Finland and Sweden – showed that the nearly zero-energy buildings constructed in Estonia are most energy efficient. In other words, their energy consumption is the lowest.

“The reason for our success story in building energy efficiency is, besides the 15-year sterling work carried out by our researchers and engineers, also the fact that Estonia as a fast-evolving country was one of the few in Europe to establish minimum energy performance requirements in 2019 with the ambition following the cost-optimal calculations results,” professor Jarek Kurnitski, the head of Tallinn University of Technology – or TalTech – NZEB Research Group, said.

“This approach was initially planned also by our neighbouring country Finland, who, however, bowed to market pressure and opted for a slower development path. This meant slightly lower construction costs, but significantly higher operation costs in the long run.”

Improving energy efficiency in the coldest zone

In Europe, climate zones are divided into four. Estonia, together with the other Nordic countries, is in the fourth – the coldest zone. When benchmarking NZEB requirements against European Commission’s NZEB recommendations, the differences in national methodologies that affect the results of the calculations must be taken into account. For example, Finland consumes nearly twice as much domestic hot water per person as countries in Central Europe.

The international research group draw its conclusions by taking into account the NZEB requirements in force in the European Union, which are expressed as national energy performance indicators.

The “primary energy indicator” means total weighted energy consumption per heated square metre of a building. It is calculated not based on the total cost of energy consumption, but by using conversion factors, which take into account the primary energy content of energy delivered into the building.

The conversion factors as well as many other input data differ from a country to another. National nearly zero energy performance indicators must be calculated based on cost-optimal levels, by determining the present value of a 30-year life cycle. The costs are composed of the construction costs, 30-years maintenance and operation costs with interest and increase of energy prices, which is why energy costs play an important role.

“Finding the most cost-effective energy-efficient solutions is an economic-technical optimisation task the building scientists need to tackle. However, we should not split hairs upon improving energy efficiency, because in order to achieve cost-efficiency, construction costs must be kept under control,” Kurnitski, who is also leading the “Zero Energy and Resource Efficient Buildings and Districts” centre of excellence at TalTech, said.

Low construction cost not sustainable in the longer run

Why have many countries not been as successful as Estonia in achieving the energy efficiency goals?

In Finland, for example, the 10-year economic recession created an unfavourable environment, which made the decision makers cautious and, instead of targeting low life-cycle costs, a course was taken to achieve as low construction cost as possible. This solution is not sustainable in the longer run. In Sweden, the process of preparing the requirements took too long, which explains a relatively low ambition of the requirements set out within the prescribed deadline.

“Strict energy efficiency requirements constitute a kind of consumer protection for a house or apartment buyer. Energy efficiency would never improve only by considering construction market preferences – it is profitable for the developer to build at the lowest possible cost, because the buyers are looking for a home and usually do not take later high operation costs into account at the time of purchase,” Kurnitski noted.

In Estonia, the first energy efficiency requirements based on primary energy use were established in 2008. In 2013, the requirements became stricter and from 2019-2020 NZEB requirements were established (from 2019 valid for public buildings and from 2020 for residential buildings).

“Estonia has trusted its scientists, responded quickly and flexibly to the changes and achieved rapid improvement in energy efficiency along with economic growth. In 2013, we reached the same level as Sweden, Finland and Norway, but now we are a step ahead of them,” Kurnitski observed. “Somewhat surprisingly, Estonia had the courage to establish ambitious NZEB requirements by regulations and make the construction sector stick to the requirements.”

Heating costs are four times lower than in the 1970s

Energy efficiency requirements shall be reviewed every five years. In 2013, the required energy class in an energy performance certificate was C; class A is laid down now by NZEB requirements. More classes may be introduced in the future, for example, class A+++ is used already as the highest class for household appliances.

Energy costs have decreased significantly in modern residential buildings. For example, compared with an apartment building built in the 1970s, the energy consumption in a modern zero-energy building is more than twice as low and the heating costs are even more than four times lower.

The international research group included researchers from TalTech, Aalto University in Finland, SINTEF in Norway and Växjö in Sweden. An article on the work of the research group “NZEB requirements in Nordic countries” was published in REHVA Journal in December 2019.

Cover: A new residential building in Kalamaja, Tallinn. Photo by Tõnu Runnel.