In the autumn of 1944, as the Red Army advanced, around 80,000 Estonians fled their homeland, first seeking refuge in Germany and Sweden before many resettled in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada and Australia; it is time to reflect on the plight of our parents and grandparents who escaped the terror and brutality of Soviet occupation.*

In August and September 1944, as the Second World War raged, tens of thousands of Estonians scrambled to board anything that could float – from ships to small wooden fishing boats – in a desperate bid to escape their war-torn homeland, which would remain under Soviet occupation until 1991.

Many nations generously opened their doors, and these refugees went on to build productive lives in their new adopted countries.

People fearing the Soviet Union

Estonians had begun fleeing to Sweden as early as the spring of 1943, but the exodus swelled in August 1944 and reached its peak between 19 and 23 September, when it became clear that the German front was collapsing and Soviet forces were poised to reoccupy Estonia.

The overwhelming majority of Estonians did not support either occupying power – their country had simply been caught between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. The Soviets had briefly occupied Estonia from 1940 to 1941, inflicting even greater suffering on the population than the Nazis, which explains why so many Estonians feared the communist regime above all.

The Soviet Union deported more than 10,000 people to Siberia and executed or imprisoned many of the Republic of Estonia’s former politicians, ministers, judges, priests, entrepreneurs and landowners. Large estates and businesses were confiscated. The NKVD – the notorious Soviet secret police, infamous for extrajudicial killings – carried out at least one massacre in Estonia, in Tartu, where 193 detainees were murdered.

Not all of Estonia’s refugees survived. Stormy seas and enemy fire are thought to have claimed the lives of up to nine per cent of those who fled. Of the people who managed to escape by 1944, most found refuge in nearby Sweden and Germany. Thousands ended up in displaced persons’ (DP) camps in Germany, which became their temporary home for several years.

In war-torn Europe

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Europe lay in ruins. Around sixty million people had been killed, nations were shattered, and between eleven and twenty million Europeans were displaced.

Germany was occupied by the Allies and divided into four sectors – British, American, French and Soviet. Millions were left homeless and dependent on foreign aid for survival. By 1945, around 200,000 Baltic people were registered in Germany as displaced persons, including some 33,000 Estonians.

In 1945, the military authorities in the British, American and French sectors set up displaced persons’ (DP) camps to provide refugees with temporary shelter, food and medical care. Hundreds of such camps were established across Germany, as well as in parts of Austria and Italy. Later that year, responsibility for running them was transferred to the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), and in 1947 to the International Refugee Organisation (IRO).

The original purpose of the DP camps was to repatriate people to their countries of origin as swiftly as possible. By the end of 1945, the military authorities had returned more than five million displaced persons, but it quickly became clear that the same could not be done for the Baltic peoples. Although the war had ended, their homelands remained under Soviet occupation, and going back would have meant persecution, deportation – or even death.

Life in DP camps

On first arriving at a DP camp, many felt an immediate sense of relief. The camps offered a measure of security – a roof over their heads, regular meals, and the hope of being reunited with lost loved ones.

Yet there was no room for complacency. Camp residents lived with the daily fear of being extradited to the Soviet Union. Many Estonians had pinned their hopes on the US Army liberating their homeland from the Red Army, but this was never on Washington’s agenda. For those in the displaced persons’ camps, the only option was to wait and see what the future might bring – and to survive as best they could in the meantime.

In the DP camps, people were grouped by nationality. On arrival they registered their details and were issued with a displaced person’s identification number – for instance, this writer’s grandmother Hertha was given the number 064057. Accommodation varied from camp to camp: former military barracks, schools, hospitals, private homes, hotels and even airports were pressed into service to house the refugees.

Camp life was culturally vibrant, particularly among the Baltic peoples. Many of those who had fled the Baltic states were intellectuals, farmers, craftsmen and artists, bringing with them a wealth of skills. They set up newspapers, workshops, theatres and training centres that fostered a strong sense of community. The workshops produced finely crafted goods from wood, leather and textiles, while embroidery was especially popular.

In the early days, conditions in the DP camps were often grim. Refugees were sometimes housed in quarters once used by forced labourers, or in accommodation that was basic at best and frequently substandard. Overcrowding was common, food shortages persistent, and as if life were not already harsh enough, the camps were soon struck by outbreaks of tuberculosis.

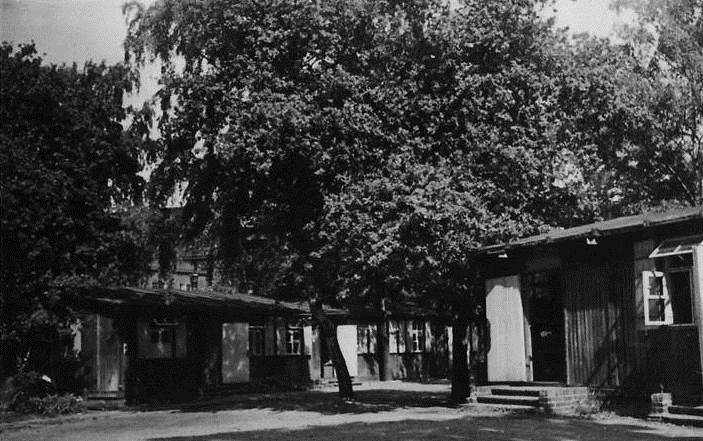

Tuberculosis was rife in some camps. Zoo Camp in Hamburg, in particular, saw many cases that led to numerous deaths. The buildings there had originally been constructed by the Blohm & Voss company, a shipping and engineering firm, to house forced labourers during the war. Made of timber, they were often damp and cold – ideal conditions for tuberculosis to spread. The Baltic University was first established at Zoo Camp before its students were relocated to nearby Pinneberg, where the stone buildings provided far better conditions.

Not all DP camps were plagued by health and welfare problems. Geislingen Camp, near Stuttgart in the American sector, was even described as “the Hilton of DP camps”. The writer’s distant relatives, Heino and Aili Lestal, lived there after the war and recalled the conditions as being very good.

Aili – a spirited 91-year-old living in Canada at the time of writing – recalls that Geislingen was a purely Estonian DP camp of around 2,000 people housed in confiscated German homes. Each family had a single room, which at least allowed for a degree of privacy. Seventeen people lived in the house where Aili stayed, while her future husband, Heino, was in the house next door.

Finding new home

Many people found love in the camps – a welcome distraction from the dangers and hardships that surrounded them.

The writer’s Estonian grandparents met and fell in love while living at Zoo Camp in Hamburg, marrying soon after their arrival in Australia in 1949. Heino and Aili also wed at Geislingen, spending their “honeymoon” and New Year’s Eve aboard the SS Vollendam as it sailed to Australia in 1948.

The announcement of mass emigration programmes by countries facing labour shortages triggered an exodus from the DP camps in 1948 and 1949. Belgium was the first to open its doors on a large scale, seeking 20,000 coal miners. The United Kingdom and Canada also offered opportunities, though these required sponsorship.

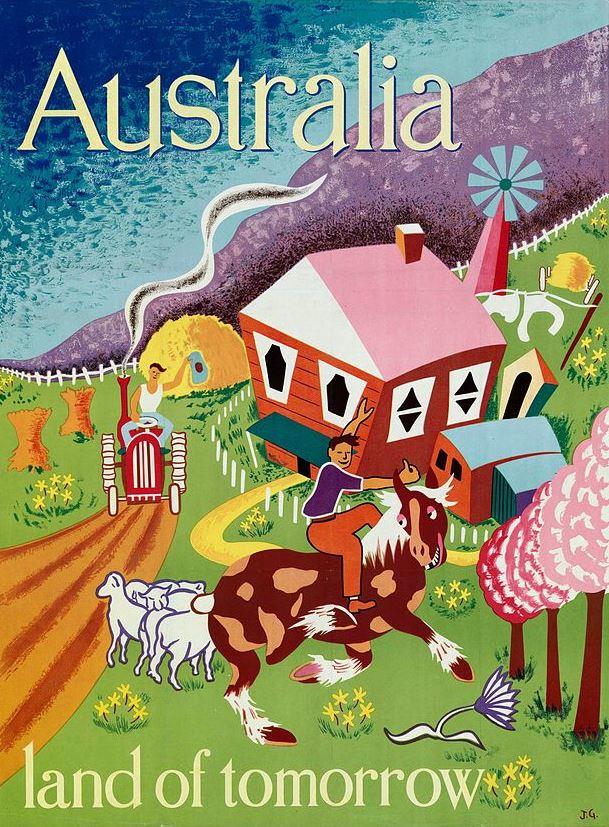

The Australian programme, known as the “DP Group Resettlement Scheme”, was regarded favourably by both the IRO and the displaced persons themselves. Unlike other schemes, which required applicants to be sponsored by a friend or relative already living in the destination country, the Australian government acted as sponsor, making the process far simpler.

Australia not only accepted single men and women into the programme but also welcomed families. This gave peace of mind to those who feared being separated from their loved ones.

The United States was slow to adopt a refugee policy and imposed several exclusions. Those suffering from tuberculosis, for instance, or anyone who had served in the German Army were not admitted. Many displaced persons favoured the Australian resettlement scheme for one compelling reason: it was far removed from Europe and its turmoil.

On leaving the DP camps, people were issued with a “Good Conduct Certificate” recording their name, date of birth and the date they had first entered the camp. The document also confirmed that they had not been convicted of any crime or misdemeanour.

Land of tomorrow

The writer’s Estonian grandmother Hertha had dreamed of emigrating to America, but her application was rejected. She later joined her husband in Australia, where they began their new life together. On arrival, they stayed at the migrant reception centre in Uranquinty, rural New South Wales, where they learned about Australian culture and began to speak English.

All migrants were required to complete a two-year work contract with the Australian government. Once this obligation was fulfilled, they were granted residency and full freedom of movement. Many went on to take Australian citizenship and settle permanently, while others later left to be reunited with family members in other countries.

The post-war mass migration schemes were a remarkable success. They allowed people not only to rebuild their lives in peace but also to contribute meaningfully to their new societies. They brought with them skills, knowledge, culture and cuisine – elements that continue to enrich daily life to this day.

Australia has gained enormously from its migrant population, and today people live there in relative harmony. Many other countries also accepted refugees. The total resettlement figures were: Venezuela 17,000; Belgium 22,000; Brazil 29,000; Argentina 33,000; France 38,000; the United Kingdom 86,000; Canada 157,687; Australia 182,159; and the United States 400,000.

Photos courtesy of Tania Lestal and Estonica.org. Please note: this article was originally published on 14 September 2015 and lightly updated on 19 September 2021 and 19 September 2025.

great article, thank you

The refugees of WW2 were of the same race and similar and symbiotic cultures/belief systems.

Big game changer.

How much more wrong was it to steal the homes of innocent German families living in Estonia and contributing greatly to the wealth and culture of Estonia, murdering those Germanic descended families whom had been living in Estonia peaceably for hundreds of years, merely but for the fact of their ethnicity, than it was for the Spanish Jews to steal America and slaughter the Natives? Crickets……

Both my parents fled their countries during 1944/46, my mother Estonian ,my father Ukrainian, both meet each other in Germany displaced camp, travelled to live in Australia, spent time in Bonagella immigration camp and were married at the camp, bilited to work in Horsham Victoria, brought land, built a home and had 3 children, we are all very proud of our parents for what they had to go through during those years as well as everyone else.

My mother and I spent time in the DP Camps. what I recall was that it was very substandard to the meagarst standards. To many German people we were Ferflucte Ouslanders. Hard as that was to take, I personally now can understand some of those emotions – based on the influx of so many foreigners into their country. To us the Ferflucte was a small burr to bear, compared to what my Mother perceived living with Kommunist Russians would have been like. I think we were in the French sector, my Mother became engaged to a French General, the son of the President of Algiers; when his family rejected her as a commoner, she somehow contacted an Uncle in Canada, who accepted us as Refugees, she served her two year worker contract, met and Married a Canadian farmer, happily produced a Half Brother for me in Canada. My Mother taught me to always be Canadian, to respect the customs, language and so on, we became Canadian.

My Grandmother remained in Estonia and was “locked into the Kommunist regime, no correspondence for years, subjected to inhumane domineering rules imposed by the Russians. My divorced Father (whom I never met), was conscripted to Russia, he eventually was able to get back to Estonia, sadly I’m sure with emotional trauma he had endure just trying to stay alive in Kommunist captivity (modern day called PTSD); he was able to get back to our homeland, he re-married and had family, where I am proud to have another Half Brother in Estonia. I am very proud of my Estonian roots, I call myself a Canadian/Estonian.