“Despite the fact that I love it in Israel, I’ve always had this sense of my Estonian roots. I think it’s great, because there was a lot of good (in Estonia). And it’s also good because the bad things that happened in Estonia, also taught me a great deal,” says Shmuel Lazikin, 64, in Eretz Yisrael – the Land of Israel – that has been his homeland for the last 22 years.

Shmuel was born in Tallinn in 1948, four years after the Soviets came for the second time and stayed for almost 50 years. Hence the comment about “bad things”– it wasn’t easy to be Estonian in these years of hardship, and it was even harder to be an obedient Jew. These were the days when religion was suppressed, traditions wiped out and people subjected to a regime everyone loathed.

Estonia – the best place in the Soviet Union

His family had lived in Estonia for 250 years. “There was no question for my parents whether to enrol me in an Estonian- or Russian-language school. My native tongue is Yiddish, we spoke it at home, and our second language was Estonian.” Shmuel didn’t speak Russian – interestingly, he only learnt it after he had immigrated to Israel decades later.

“I realised in Estonia that the best place to be born would have been Israel, but within the Soviet Union, Estonia was absolutely the best place to be born,” he recalls. Why? “My mother’s brother Abraham Gurevitsh – blessed be his memory – was the Rabbi in Estonia and he had a great influence on me. Secondly, in an Estonian school I learnt about Russia’s “moral values” quite quickly.” On the other hand, he says, quite often the Jews were a tiny bit more preferred compared with the Russians: “both us and Estonians were oppressed.”

Up to the Second World War, the Estonian Jewry enjoyed a flourishing cultural autonomy in Estonia. Estonians, traditionally fairly tolerant people, did not have anti-Semitic tendencies. The Soviet occupation, and especially the German occupation brought all that to an end. The Estonian Jewish Community was annihilated, and Estonia was declared judenfrei. “And I knew this didn’t happen only through the hands of Germans,” Shmuel hints at some of the Estonian Nazi collaborators. Some of the anti-Jewish sentiment remained in Estonia even after the war. “At school, I was stressed out the entire 11 years. I started properly learning only after graduation.”

A big change

At the age of 42, in 1990, at the brink of the Soviet Union’s collapse, Shmuel made a life-changing decision. He and his family sold their car and flat, gave the money they received to relatives, and took a ferry to Finland. He had began his journey to Israel, the Promised Land: “For me the Soviet Union was the most awful place in the entire world. In some ways even worse than Nazi Germany.”

Shmuel and his family arrived in Finland with hands in their pockets. They didn’t have anything, not even passports. “I remember how comfortable it was to travel without it,” he calls to mind. However, the Finnish border guards didn’t share his enthusiasm and threatened to either send them back to theSoviet Union, or to arrest them. “I gladly agreed to go to jail. Our friend in Finland, Rauno Nuoraho, had made a deal with the Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs that we were to be allowed in the country, so I asked them to arrest me and told them that I would give a press conference in the morning from my cell.”

“The border guards were very nice people. They started to look for our names in most wanted lists. When Rauno saw that our interaction with the authorities was dragging, he spoke to one of the senior border officials and promised that he would take us to his place to spend the night, and if we didn’t get the permit from the foreign ministry, he’d bring us back in the morning.”

Surprisingly, it worked. The Finnish border guards let Shmuel and his family go. “By the morning we had solved all issues and I didn’t have to give the press conference I had promised.”

A huge donation from a complete stranger

But Shmuel’s luck hadn’t run out. “A few days after he had arrived in Finland, Rauno told me that a Christian woman wants to donate 5,000 US dollars for our family to make our journey, and settling in a little more comfortably. When I wanted to thank this lady, Rauno told me that she wanted to remain anonymous. “The warm attitude of this Christian family towards us was something I had never felt before,” Shmuel remarks with a smile. “To this day I have no idea – was the kind donor really some anonymous Christian lady, or was it Rauno himself?”

For Shmuel and his family, the 5,000 dollars were like a fairy tale. They were coming from the Soviet Union, they were poor – and then suddenly they were travelling loaded!

Learning Russian in Israel, of all the places!

As mentioned earlier, Shmuel didn’t speak Russian in Estonia and he only learnt it, once in Israel. “It wasn’t easy to learn it in Estonia. It was a foreign language, not too many lessons. However, in Israel, one million Russian Jews arrived within a short space of time, after the collapse of the Soviet Union. You could hear Russian everywhere; a Russian radio station started and Russian newspapers appeared on sale. At first, this gave me information in a tad more understandable language than Hebrew was for me at the time.”

Soon after that, Shmuel began giving lectures on Judaism in Russian. For the last 16 years he has worked at a private learning centre for children from mainly Russian Jewish families.

“I think it was easier for me to start a new life in Israel, than for many others coming later,” he asserts. “Israel helped us a great deal. When I left the airport, I already had my passport and a cheque for an amount sufficient for renting a flat and keeping it together. Using it sparingly, it was possible to live on it.”

Blogging in Estonian about Israel and Jews

“When reading news about Israel in the Estonian media, it quite often feels as if the author doesn’t know absolutely anything about what he’s reporting on. The stories are dull, translated from somewhere and almost never impartial – there were exceptions like Sten Hankewitz’s articles (Shmuel insists on adding this remark to this article). It either feels that the writers are completely influenced by the left wing media’s stance, or that their level of intelligence wasn’t necessarily too high.”

Another thing that annoys Shmuel are many readers’ comments in relation to matters concerning Israel, which indicates a lot of ignorance among many people. “And thus I came to an idea to create my own portal that would at least try to offer an alternative to the disinformation prevailing in the media – an issue not just in Estonia but everywhere.”

With that in mind, a blog called Listen,Israel was born. “I want to write about both good and bad things. About problems and accomplishments. Of course, I haven’t yet achieved much, because I am working on it out of my free time and I don’t have a lot of it.”

With that in mind, a blog called Listen,Israel was born. “I want to write about both good and bad things. About problems and accomplishments. Of course, I haven’t yet achieved much, because I am working on it out of my free time and I don’t have a lot of it.”

His blog has 10-20 readers a day, which isn’t a lot, Shmuel admits. But it definitely is a start, and one can hope that these 10-20 people learn something that they won’t necessarily learn from the mainstream media. “One day I hope to find a sponsor and then dedicate more time to it. Right now I don’t have the funds to advertise it, nor offer photos or videos that could potentially make it more interesting.”

“One subject in the portal is especially sacred for me – Memorial Day. In December, I’ve covered this for a year already. It’s about Jews that have been murdered – throughout centuries, every day.”

“Estonians should build Estonia together”

Are Estonians home and Estonians abroad different? “To a certain extent, yes,” Shmuel says. “But in my opinion, all Estonians in the world should stick together – only this way they will prevail. We Jews know about assimilation very well. There are assimilated Jews everywhere, even in Estonia.”

“It would be for the best if Estonians returned from around the world, went back to Estonia. They could build the country together, with a purpose, and maintain their roots. I remember, when I worked for the Estonian Philharmonics, I discovered Estonian folk traditions for myself. Read the first book on the subject within days. After that, I started giving lectures and concerts on the subject – we had a musician, two singers and two dancers. We were all on stage, me included, in Estonian traditional clothing. People were always astonished to see this – it wasn’t every day they saw a Jew in Estonian traditional clothing talking to Estonians about their traditions!”

Shmuel notes that in his opinion, it’s harder for diaspora Estonians than it is for diaspora Jews to keep their traditions alive – because for Jews, there’s the Torah (the Jewish Bible) that ties them together. As Shmuel points out, the Torah has been the spiritual foundation of the Jewish people that has kept them together for millennia. “It means that Estonians have to work harder on upholding their uniqueness in the world. If that were to disappear, G-d forbid, the entire world would lose.”

“I want to tell all Estonians, at home and abroad – stay Estonian. Don’t assimilate. After all twists and turns in history, your independence is G-d-given and you have to cherish it with your heart and soul!”

I

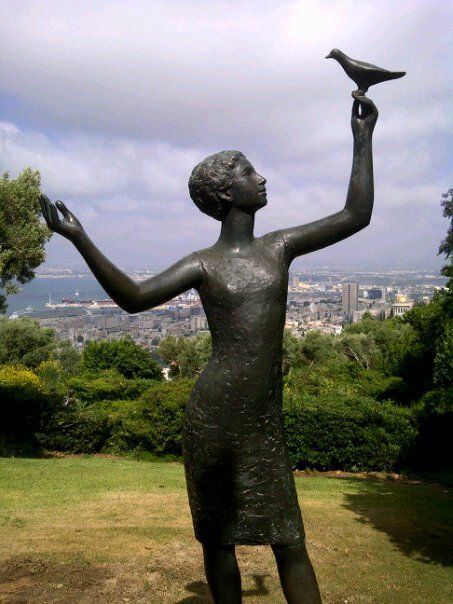

Cover: Shmuel Lazikin in Israel (photos courtesy of Shmuel Lazikin/Silver Tambur/Boris Gorsky/Estonian Jewish community).

Enjoyable article. I once interviewed the great Estonian comedian Eino Baskin who was head of the Jewish Estonian society. He also gave an interesting perspective of his life in Estonia. Thanks for the thumbs up. An Esto-Canadian journalist/educator..

Fascinating article for me. I’m half-Estonian, half English, born in far east, childhood in Europe, education and life ever since in England. One visit to Tallinn & some family members in 1997, ashamed not to have mastered the language. Enjoy reading about Estonia, always disappointed articles come across as so “wooden” – not the kind of stuff that will really interest or promote Estonia abroad. So I shall further into Shmuel for a bit of insight…..

Ma ei usu, et ta on vene keelt õppinud alles Iisraelis. Selleks on see temal liiga hea. Seda enam, et ma kuulsin paar korda sama lugu leedukatest, kelle “rusų kalba” oli ka kiitust väärt.