Europeans should start learning about other European countries, cultures and history from as early age as possible – ie at primary school – to have a better mutual understanding of fellow Europeans later in life, Silver Tambur, the editor-in-chief of Estonian World, writes.

In 2016, I joined the IJP – the German-run independent International Journalists’ Programme that offers European journalists the chance to work abroad for a couple of months (I spent two months at the English department at the Deutsche Welle headquarters in Bonn). Each year, the IJP also organises short eye-opening, educational trips to various European countries – just at the beginning of September, a group of us visited the Slovakian capital, Bratislava, where we learned more about the local media situation and the country in general.

We don’t know enough about fellow European member states

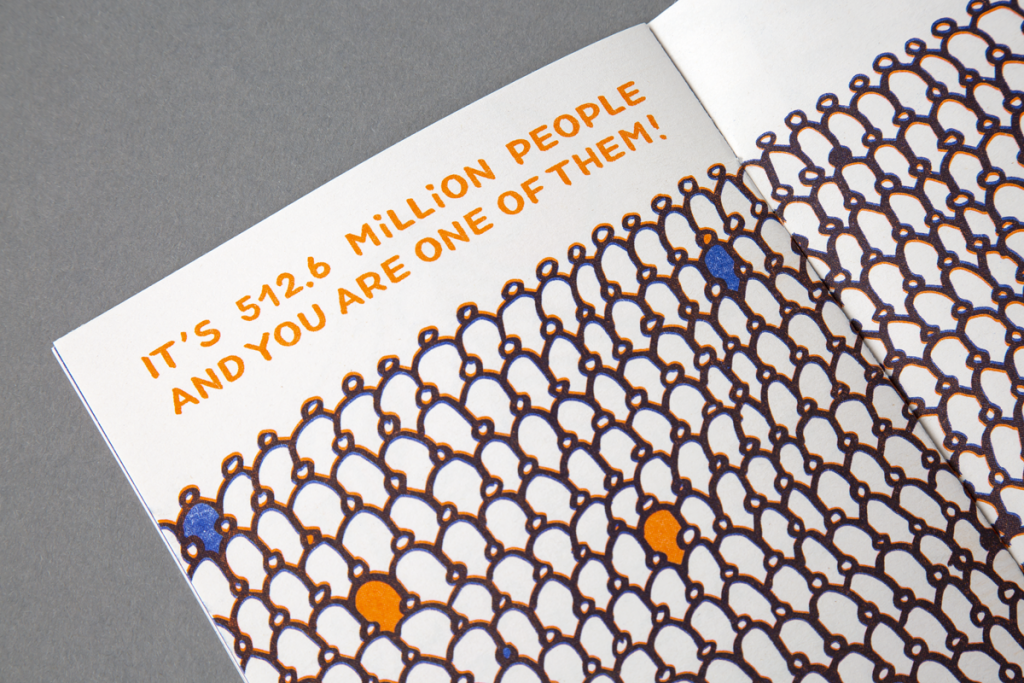

None of us – journalists from Estonia, Poland, Hungary, Latvia, the Czech Republic and Germany – had even been to Slovakia, and none of us knew to a great extent about that country. Yet, Slovakia has been a member state of the European Union since 2004, joining with nine other countries that year. We learned a great deal on the spot – but there are 50 sovereign states in Europe and 28 member states of the EU. Unless one is a globe-trotting millionaire, without any other commitments, we simply cannot visit all those countries within a short span of time to learn about great lengths.

Ah, yes, the internet. All you ever need is there, right? Well, many researchers have years ago pointed out that our brains aren’t all that good at processing the amount and the speed of data and information coming at us all the time now. Besides, when was the last time you researched, without a specific reason, the role an individual European country played historically, for example?

So, I question myself – shouldn’t we know more about respective EU countries and European countries in general and start learning it all at school? Sure, we learn about many cultural, artistic, political, economic and religious milestones in history – but mostly through the angle of major European powers: Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, perhaps also the Netherlands and Austria. When it comes to ancient history, also Greece.

We need more organic integration

At the same time, in countries all over Europe – from Hungary to Poland, from Italy to Germany and from Sweden to Estonia, radical populists and the far-right have raised their ugly heads, stirring divisions and calling for “the return of nation states”. They spread lies not merely about immigrants from outside Europe, but also about fellow EU countries – the Leave campaign’s fearmongering before the EU membership referendum in the UK in 2016 was a prime example.

The populists have also made the allegedly bureaucratic power mechanisms of the European Union – its institutions in Brussels – as one of their targets. The result is that there are many people who think of Europe as an institution, rather than one of the greatest centres of people and ideas – in culture, economics, education, philosophy, you name it.

For many, it feels there’s a top down European integration. But Europe needs once more organic, from bottom to top integration – an enlightening and joyous feeling that we’re part of a great European culture that binds us all.

Pan-European education

Right now, European studies are mostly the privilege of the universities, but we, Europeans, should start learning about other European countries, cultures and history from as early age as possible – ie at primary school – to have a better mutual understanding of fellow Europeans later in life. Every country has its own educational system and teaching methods, but a common European curriculum would help – and again, this should not be compiled by the centralised EU institutions, but perhaps by one of the educational pan-European non-governmental bodies. Since we’re in the technological age, the common curriculum could easily be systematised by an app.

Perhaps slightly ironically, taken into account the recent Brexit mess in the UK, it was the great British prime minister, Winston Churchill, who said in a speech in Amsterdam in 1948: “We hope to see a Europe where men of every country will think as much of being a European as of belonging to their native land, and that without losing any of their love and loyalty of their birthplace.”

It is important that more people see the big picture and feel like Europeans – a narrow-minded nationalism in Europe is not a recipe for success in the globalised world where increasingly, more and more countries outside Europe, are ruling the waves. Education is surely one of the most important ways to achieve an intelligent view of that big picture.

The shorter version of this article was originally published in Slanted magazine.

The opinions in this article are those of the author. Images courtesy of Slanted magazine, except where stated.