Aure, a 28-year-old blogger from Belgium, analyses how the Ukrainian war inverted the power dynamics in the European Union: Estonians, very much like the Poles, Slovaks or the Romanians can no longer accept playing second-rank roles due to their lack of confidence based on false historical narratives and Western cliches.

The Ukrainian war highlighted how the EU is still divided into two parts:

- The Western bloc

- The post-Soviet bloc (countries formerly occupied by the Soviet Union in Eastern Europe)

While the former reacted with surprise and panic in the aftermath of the Russian invasion, the latter reacted with calm and fortitude.

The degree of difference between these two outlines how far apart the certainties regarding Russia’s intentions stood on each side, at least up until the 24 February 2022.

The proactive role of the East in this crisis and the countless mistakes of the West have inversed the traditional leadership roles.

Power and credibility in the European Union have been redistributed, which will strongly impact the EU’s internal functioning in the decades to come.

Here’s how.

Two realities

The Western bloc has been failing to understand Russia since it became a Soviet Socialist Republic in 1917 and formed the Soviet Union.

The popularity of communism in elections in Italy and France in the middle of the 20th century and the endorsement of the Soviet Union by many artists and intellectuals (who did not actually live under Soviet rule) show that very few in the West knew what was happening beyond the Iron Curtain.

Surprisingly, this ignorance persevered even after the end of the Soviet era.

Whatever Western Europeans know about Russia today mainly comes from James Bond movies.

Western Europeans don’t travel to Russia. They don’t read Russian novels. They don’t watch Russian movies, they don’t learn Russian history, and even less so the Russian language.

As a result, they don’t know what Russia is, where Russia comes from, and what role Russia played in what is today the post-Soviet bloc.

To a random Dutch or Spanish, Russia is a faraway country that has more in common with Asia than it has with Europe. Western Europe is much more oriented south and west than it is east.

The problem is that the Western political class’s beliefs about Russia aren’t much more evolved.

When Germany signed the treaty for Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline in 2011, it chose to ignore the two Chechnya Wars, the Russo-Georgian War and the repeated calls from its Eastern European and American partners that Russia could not be trusted.

To Westerners, Russia in the 21st century was a hyper-conservative-slightly-totalitarian-yet-friendly country – nothing like the USSR used to be.

When the Baltic states came to Brussels to plead for more defence capabilities in the region, the Western bloc raised an eyebrow and replied: “Russia isn’t a threat.”

No one in the West thought they would dare move into Ukraine because “they have nothing to gain from it and everything to lose”.

Everyone in the Baltic knew they would – which is why one of the first things they did after regaining independence was to join NATO.

Given the fact that the most recent domestic conflicts the West was embroiled in were between Westerners (the Second World War), the Western bloc is not used to encounter an opponent that thinks in different terms.

And when it does, it usually fails to grasp it, as we have seen in Afghanistan, Iraq – and how we’re currently dealing with China.

When Russia seized Crimea in 2014, the Germans didn’t budge. Nord Stream 2 was going ahead.

The deeper the sleep, the more painful the awakening.

A cold shower

Western Europeans woke up from a long dream at the end of February 2022 and began to panic.

First, they realised that most of the decisions they had made in the past ten years (at least) had been wrong.

It had been wrong to buy Russian gas. It had been wrong to plan to buy more Russian gas. It had been wrong to shut down nuclear power plants. It had been wrong not to supply Ukraine with more weapons. It had been wrong to assume that Russia had friendly intentions. It had been wrong not to have an army. It had been wrong to tolerate the seizing of Crimea.

Second, they realised their Eastern partners (whom they hadn’t really taken seriously since they joined the bloc in 2004) had actually been right in many regards.

This isn’t often talked about, but the common Western European has remained condescending towards its Eastern partners despite Eastern countries outcompeting the West in many domains in recent years.

This power dynamic was until now, reflected in the internal functioning of the EU.

The functioning of the EU

To understand why Russia’s invasion will impact the working of the EU, we first need to observe how the EU functions.

The founding members of the EU have been leading the group since its inception in 1952 – and left little power to the newcomers.

EU candidate countries today must first comply with a range of economic and political criteria before formally being admitted into the club.

Long story short: to join the EU, you need to imitate (if not copy) what the EU countries are already doing.

This implies that the founding countries have a right to validate or not the efforts of transformation of the candidate countries. They have the power to say: “you belong to Europe”; or “you don’t”.

Joining the EU is therefore a fairly humiliating process for the candidates. They must go through a series of changes to obtain validation from the union without being sure they will get in.

It is, as a result, easy to understand why the EU has been directed by the six founding member countries (Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, Germany, Italy) since the beginning.

Today, the president of the EU Council is Belgian, the president of the EU Commission is German and the president of the European Parliament was Italian (until he died and was replaced by his vice president, a Maltese).

So far, every candidate or new member of the union understood and accepted the bargain.

After all, the benefits weren’t small: Schengen, economic integration, access to funding grants, international recognition.

While the EU imposed reforms, the latter also had the advantage to leave the candidate countries better off at the end (more democracy, less corruption, more money).

As long as the founding members led well and made the right decisions, few complained.

Two decades of bad leadership later, things have considerably evolved.

The mistakes of the West

The EU forever changed after the financial crisis of 2008. The Western bloc realised it wasn’t as rich as it thought on one hand, and that it spent too much on the other.

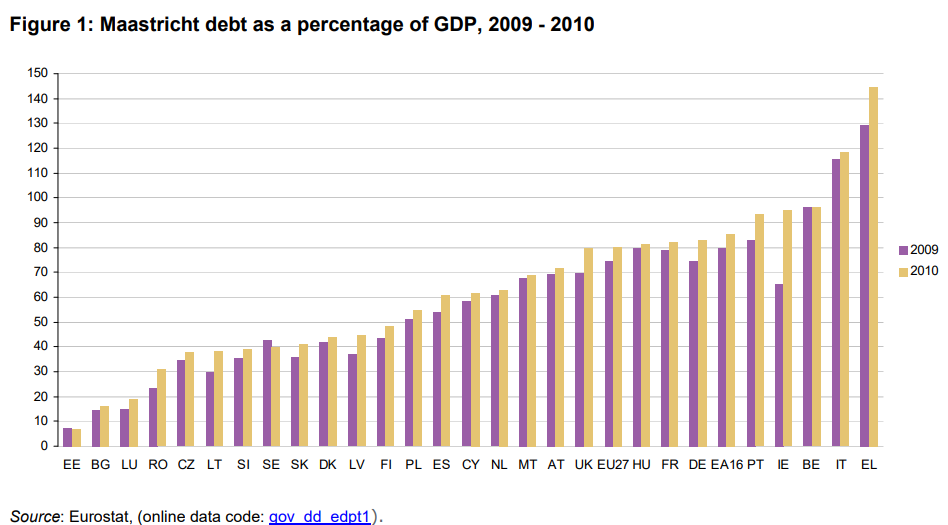

In the subsequent years, Germany went on to impose draconian and economically misguided austerity policies on a range of countries whose deficit was way above the 3% rule.

Why misguided?

The 3% deficit rule has never had any economic backing. It just “sounds nice”.

Economic guidelines have never been sanctioned equally across the bloc.

The scientific consensus on austerity was wrong.

Greece went on to live ten years of dramatic economic pain because the richer (and economically healthier) countries had decided so.

Note that for the newcomers, the Greek crisis was a bleak moment. I remember reading that Slovakians, who earned much less than the Greeks at the time, were understandably angry to have to pay for the debt of a richer country.

To think that all the efforts ended up in vain anyway…

As we can see in the illustrations above, debt today is much higher than it was ten years ago for most countries.

The same pattern repeated for almost all decisions the EU founding members have been taking the last decade or so:

- Relying on Russian gas

- Abandoning nuclear energy

- Failing to spend 2% of GDP on defence

And now, giving in to Putin’s nuclear blackmail.

Some observers have highlighted how the EU has been in constant crisis since 2005.

First, with an energy crisis, then with a financial crisis, then with a debt crisis.

Then with a migrant crisis, with another debt crisis, with another migrant crisis, with a health crisis, with an energy crisis doubled with a… war crisis.

Clearly, there is something that doesn’t work.

The attractiveness of the East

While they used to solve questions related to energy, defence and the economy, the Western bloc struggles today with an energy crisis, a defence crisis, and an economic and debt crisis that appears to be worse than in 2008.

The bottom line: the Western bloc has lost almost all of its credibility.

Meanwhile, the “good students” in the class seem to be the post-Soviet countries.

Poland has been looking for alternatives to Russian gas since 2014 and built a pipeline that links it to Norway in an attempt to diversify.

Estonia manages to maintain low taxes and low government debt and deficit.

Lithuania is the fintech hub of the EU.

Overall, the post-Soviet countries have lower levels of debt, lower levels of taxes and higher levels of GDP growth.

Economically, and now militarily, they’re in an ascendant phase.

Can we say the same thing about the Western bloc?

A reversal

Ever since the EU was created, the Eastern countries had been more dependent on the West than the opposite.

This is now slowly changing.

The post-Soviet bloc has shown itself better not only at dealing with crises, but at preparing for and anticipating them.

Notice how quickly the Eastern bloc reacted to Ukraine’s invasion by welcoming refugees, providing weapons, then banning Russian tourists.

Meanwhile, the Western bloc remains stuck in questionable narratives such as “we will not retaliate in case a nuclear weapon is used in Ukraine” or “Russian tourists are welcome”.

The numerous mistakes the Western bloc has been making (and that the East has averted) outline how the West would benefit from a stronger relationship with its Eastern partners, on all levels.

Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, declared a few weeks ago: “We should have listened to those who know Putin (…) to Poland, the Baltic states and all of Central and Eastern Europe. They told us for years that Putin wouldn’t stop.”

Indeed, they did.

When I moved to Warsaw in September 2020, I made the bet that while Poland received money from France and Germany then, it will likely give money to France and Germany in fifty years.

The East is rising. Yet the West doesn’t seem to realise it.

The conclusion

It is now time for the Western bloc to get rid of the (slightly xenophobic) idea that post-Soviet countries are in any way less deserving or less competent to lead the EU than their Western counterparts.

As the last ten years have shown us, this is clearly not the case.

The West can no longer move forward without inputs from the East – and it knows it.

However, stronger participation of the post-Soviet countries in the European decision-making process does not only demand that the West makes some space for them – it also demands that the Eastern actors step up and make themselves heard.

Estonians, very much like the Polish, Slovakians, or the Romanians can no longer accept playing second-rank roles due to their lack of confidence based on false historical narratives and Western cliches.

The achievements of the post-Soviet countries are remarkable in numerous domains.

It’s time for the Eastern bloc to leave the past behind and focus on building the future.

It’s time for the Eastern bloc to shed any remnants of impostor syndrome or inferiority complex and look with pride at their achievements of the last 30 years.

It’s time for the Eastern partners to step up and gain confidence in their leadership capacities.

They have proven to the world, since the invasion, that they were more than capable of effectively dealing with crises on their own initiatives.

They should, therefore, no longer be afraid to lead and call out the West when necessary.

Read also: Reelika Virunurm: The true cost of Germany’s stance on Russia

The opinions in this article are those of the author. * For personal reasons, the author did not wish to reveal his full identity.