Hesam YR, an expat living in Estonia, is contemplating whether Estonia could become a real home for expats who cannot renounce their citizenship of origin – as Estonia doesn’t permit multiple citizenships.

It’s not long since Estonia has started to make a name as a destination for novelty-seeking expats. Some see it as an entry to Europe while others see Estonia in its own merits and hope to stay long term. For those who settle in, the process of naturalisation is a long and eventful journey but depending on your country of origin, it might be legally or practically impossible to become a full member of the Estonian society.

Estonia has a lot to offer and is rapidly growing. This provides an opportunity for its residents to become part of the change in many innovative initiatives. But if you are thinking long term, compared with other expat destinations that have a long history of diversity, there is still a lot of room for improvement.

Due to the relatively short history of cosmopolitanism and concerns around national identity, attracting expats for the purpose of naturalisation doesn’t quite yet seem to be Estonia’s cup of tea.

At the same time, it is to be expected that after years of stay, some expats will have grown roots and find it more delightful to settle and integrate in Estonia rather than their home country. Among them, perhaps not surprisingly, many are from outside of the EU. In order to “become” Estonian, however, they would have to renounce the citizenship of their country of origin. Not an easy feat – renouncing a citizenship is legally or practically impossible for nationals of some countries, making it impossible to become Estonian, regardless of being qualified.

The journey of Estonia

Coming from the era of post-occupation without much of a reputation to go by, Estonia has come a long way in becoming more attractive as an expat destination.

I still remember that, in 2011, when I arrived in Estonia, there was hardly any international community and I was largely treated as exotic, subject to interviews in television and newspapers.

Despite ups and downs and changes of strategy in immigration policy during recent tensions between governments, undertakings such as the e-residency, the International House of Estonia, scholarships for higher education foreign students, free language courses and, of course, the growing and vibrant startup ecosystem have all contributed to the goal of making Estonia more attractive to the outside world.

As a result, Estonia has proven to have the potential to effectively absorb and use the help of foreigners to build a better future for all and perhaps also address some of its workforce, identity and preservation of cultural heritage challenges along the way.

Attracting educated and talented people ready to commit themselves to a life in Estonia is a solid strategy but not something that would happen overnight. It has taken a decade for Estonia to see an increase in the non-EU workforce.

As the expat community matures, Estonia will be facing new political and economic decisions. Whether to continue taking a business-minded approach towards foreigners living in Estonia or choose to also include them in the national narrative, is probably one of the many decisions to come. Among other things, this would mean supporting expats next to the local Russian population through the journey of naturalisation.

The journey of an expat

The reality is that in the journey of any expat there is a time when they feel like having been upgraded to a senior expat if you like. They start speaking the language, understanding local news, making sense of the cultural nuances and gravitate towards long-timers and locals rather than newcomers.

They also tend to have a stable job, a family and a strong network of people. Moreover, seeing themselves a contributing part of the society, they start appreciating a sense of belonging in the place where they live. In comparison, after spending the better part of their life in Estonia, they might not have much left in their country of origin.

Somewhere just around the corner also lies the topic of citizenship and the promise of being able to feel like having equal rights to other citizens. It is a natural turning point in any expat’s journey to start thinking about the question: could this really be my home? Home being a place where you are accepted not just as a tool in achieving a better status quo but a part of the family.

Considering the history and the struggles that eventually led to the Estonian independence in 1918 and the restoration of its independence in 1991, it is understandable why dual citizenship is not permitted in Estonia. Nonetheless, this means expats who might wish to become full members of Estonian society, will first have to figure out how to lose their current citizenship.

For some, this could be only a moral dilemma, a choice between roots and ideals, but depending on the country of origin, it might also involve quite some bureaucracy. For other countries, including Argentina, Mexico, Yemen, Costa Rica, Syria, Iran, Morocco, Guatemala, Ecuador and many more, however, it is outright illegal or practically impossible to renounce citizenship. People from these countries are neither able to lose their current citizenship nor be granted Estonian one, regardless of being qualified and fully integrated. They are effectively in uncharted territories.

There are not many expats from such countries in Estonia. Recently, the Estonian Human Rights Centre opened a court case related to a Syrian national to bring recognition to this issue.

The man has been living in Estonia for over 10 years and has an Estonian family, but is unable to renounce his Syrian citizenship. As a result, despite fulfilling all the requirements (among other things, eight years of stay and passing language and constitution exams), he is not able to acquire Estonian citizenship either.

One might rightfully point out that there is no obligation on Estonia to consider his case because, if anything, it’s Syria who should give the choice to its citizens. However, Syria could not care less and if Estonia also does not, this man has no way out of this situation.

Aside from missing out on the rights that only an Estonian national could have, his family will always have to be dealing with restrictions that are imposed on him because of his different nationality. This affects the freedom of movement and access to infrastructure for his entire family.

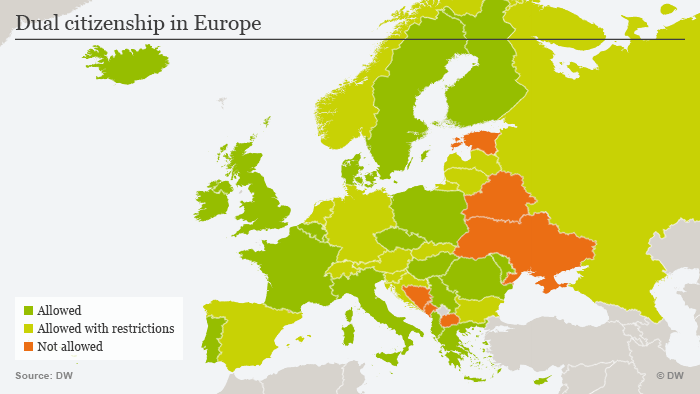

Estonia is not unique in not permitting dual citizenship. There are several popular expat destinations in Europe where dual citizenship is also not allowed – notably Germany, Netherlands, Sweden and Norway. Nevertheless, these countries have recognised the issue that renunciation is legally or practically impossible or otherwise unreasonable to fulfil in some countries and offer exceptions and workarounds in such cases.

The only exception to the single citizenship requirement in Estonia is for Estonians who acquire citizenship through birth. As a result, although dual citizenship is not permitted by law, many Estonians have multiple citizenships thanks to the fact that Estonian citizenship by birth cannot be taken away. This, however, does not apply to expats seeking naturalisation with difficulties in losing their home country citizenship.

For comparison, there are only a few countries in Europe – including Estonia, Ukraine, Belarus, North Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina – which have almost no tolerance for exceptions to the strict rules governing prevention of dual nationality. Such exceptions are needed to allow naturalisation of people from countries where renunciation of citizenship is nearly impossible.

The road ahead

Estonia has had a rough history but thanks to its overall wise strategizing, it is rapidly changing from a nation with a fragile identity into a place where all can contribute to a better future for all.

Despite countries’ complex legal systems with regards to nationality and naturalisation, there are still gaps that could use a humanitarian perspective rather than a strictly legal one. If you are an expat considering Estonia as a long-term destination and coming from a country where renouncing citizenship is not an individual’s own right, you should be aware of the complications on the way.

Perhaps the growth of economy and technological advancements in Estonia will gradually pave the way for a stronger national identity, where all who contribute to the future of Estonia have a chance at being fully recognised and diversity can be celebrated. Maybe one day it would be easier to call Estonia home for foreigners, too.

Read also: Aune Valk: Why on earth are they coming to study in Estonia?

The opinions in this article are those of the author. Cover: A group of expats at an Estonishing Evenings event in Tallinn, April 2019. Photo by Kristin Kalnapenk.

‘citizenship through birth’ – nonsense, I can give you a nice list of people, myself included, who can’t even get a residence permit let alone a citizenship based on being born in Estonia.

This nonsense dodging of people who 30 years later are a notice away from being deported from their land of birth – let me repeat that again LAND OF BIRTH! – is enough to boil ones blood.

Perfect article.

As an expat living in Estonia for 8 years and working in the country’s top university, I face the exact same difficulties.