Given that a teacher with an advanced degree earns the same salary as those with only secondary education, is it any wonder Estonia is experiencing a “teacher succession drought”?

This opinion article was originally published in Estonian in Eesti Päevaleht.

In the autumn of 2022, Estonian teaching professionals will be able to say with confidence and based on decades of experience, that a systematic and meaningful contribution to the development of the nation’s children is not the priority of any political party currently serving in the Estonian parliament, Riigikogu.

Underfunding of education has led to a situation where, in many schools, the implementation of the national curricula is no longer taking place: lessons are simply cancelled due to a shortage of teachers, or classroom work is carried out by people who do not have the requisite knowledge of the subject matter nor the skills needed for teaching. What’s more, the crisis is worsening, as older teachers leave for a well-deserved retirement and only a handful of individuals go on to teach at university.

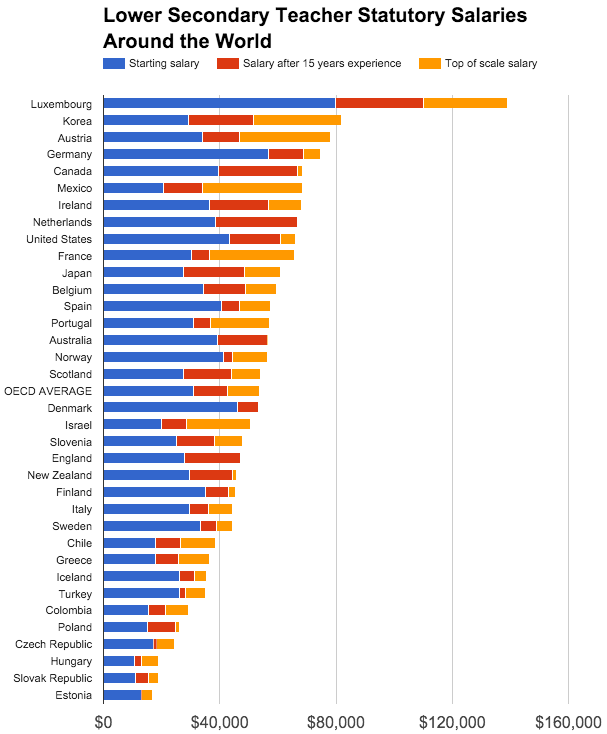

Today we are tackling two problems. Firstly, teachers’ unions are trying to retain teachers who are already working in the profession. To do this, we need a rapid increase in teachers’ minimum salaries, otherwise, we will lose these qualified instructors – many of whom have advanced degrees – to other sectors.

The Estonian Education Workers’ Union has put forward an expectation that teachers’ salaries should start at €2,000. The current gross salary for a teacher is €1,412 (net salary about €1,100), which often compels a 50-60 hour work week. This means that a physics and chemistry teacher who spent five years studying at university has a realistic hourly wage of €5 to €6. The public is misled by the claim that teachers are paid on average, and it is left unsaid that this average is the result of a situation in which teachers are treated like factory workers during the 19th-century industrial revolution.

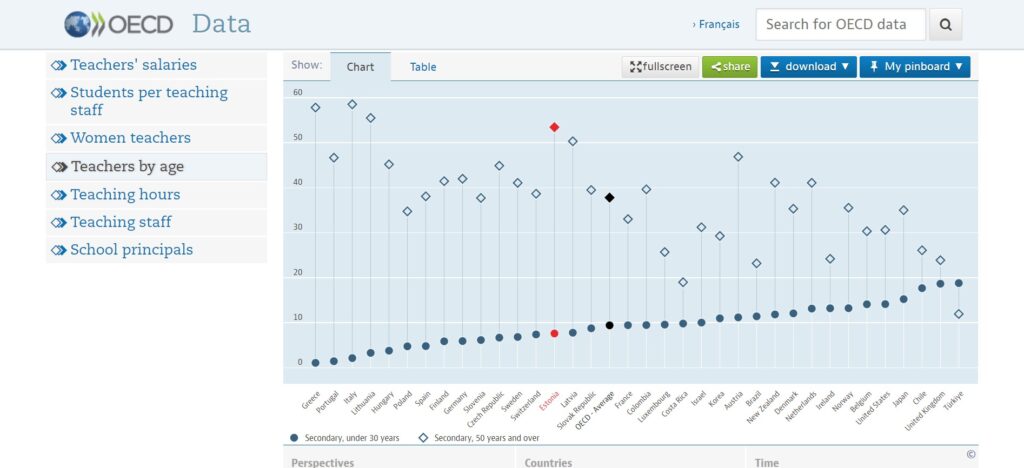

Another problem that teachers’ unions have been attempting to tackle is the “teacher succession drought”. The summer of 2022 confirmed once again that only graduate courses for primary and class teachers had full rosters. This is to say, only a handful of people are studying to become subject teachers, responsible for the systemic development of learners in grades 5 to 12.

It seems totally incomprehensible that people who have taken on the responsibility of running the country, and are privy to a definitive statistical overview of what is happening, have let the education sector sink into such a deep crisis.

The Estonian education statistics website Haridusilm shows that in 2018/2019 there were 904 teachers without a degree – ie just secondary education – which rose to 946 in 2019/2020, and 1,035 in 2020/2021. There are still 14 teachers with just nine years of education! These figures speak for themselves.

The message from the representatives of teachers’ associations, who recently gathered in Tallinn Secondary School of Science was clear: to foster the next generation, teachers need a sharp pay increase and a clear career model.

I have an excellent maths teacher colleague who meets the qualification requirements and has been a teacher for 49 years. Her students achieve outstanding results in exams, subject competitions and Olympiads; she has also worked at university for five years – and her full-time salary is €1,100 net. At the same time, a teacher with a secondary education who began teaching in autumn 2022, will also have a net salary of €1,100.

This system, in which even half a century of quality real-world work experience does not lead to any wage differentiation, has precipitated our current situation: it is not advisable to study to become a teacher because the pay is demeaning for a person with a master’s degree, the working week is 50-60 hours long and there is no career model.

The best-case scenario is that a teacher ends up in a school where most of the parents are educated and the headteacher is competent and knowledgeable about the profession. In an ironic twist, what distinguishes teachers from firefighters, policemen and doctors is the fact that the better we do our job, the less we are paid. Teachers do not work on a timetable, and hidden hours are not paid.

In autumn 2020, the culture committee of Riigikogu held an in-depth debate on the succession of teachers and the value of teaching. All concerns and possible solutions had been mapped out. Last year, however, I wrote that the pay rise for teachers thus far is akin to varnishing fingernails with gangrene.

More recently, on 12 September representatives of teachers’ associations met with members of the Estonian government and the culture committee of the Riigikogu to jointly find a solution to the teacher succession drought. After several hours of discussion, it was concluded that a significant increase in the minimum wage for teachers and a differentiation of salaries, which would require at least €132 million of additional money for the teachers’ payroll, would alleviate the situation.

Now it all depends on the political will of the government and the coalition parties: whether we solve the problem of teacher replacement or continue to lick our gangrenous fingernails.

Read also: Estonia: Where have all the teachers gone?

The opinions in this article are those of the author.