Estophile Adam Garrie argues that it’s time to establish a dedicated museum of Estonian music, with an emphasis not only on rich choral traditions and modern classical, but also on a contemporary period.

When mentioning Estonian culture to international audiences, the first thing that usually comes to mind is Estonia’s rich musical tradition. Estonia’s choral music has won global fame, so much so that the former Monty Python comedian and documentary maker, Michael Palin, remarked that it didn’t take a great deal of effort to persuade an Estonian to break into song. Over the last decades of the 20th century and well into the 21st, Arvo Pärt has become the world’s most listened to orchestral composer, something which has brought a great deal of attention to Estonia’s other great modern composers, not least Heino Eller and Eduard Tubin.

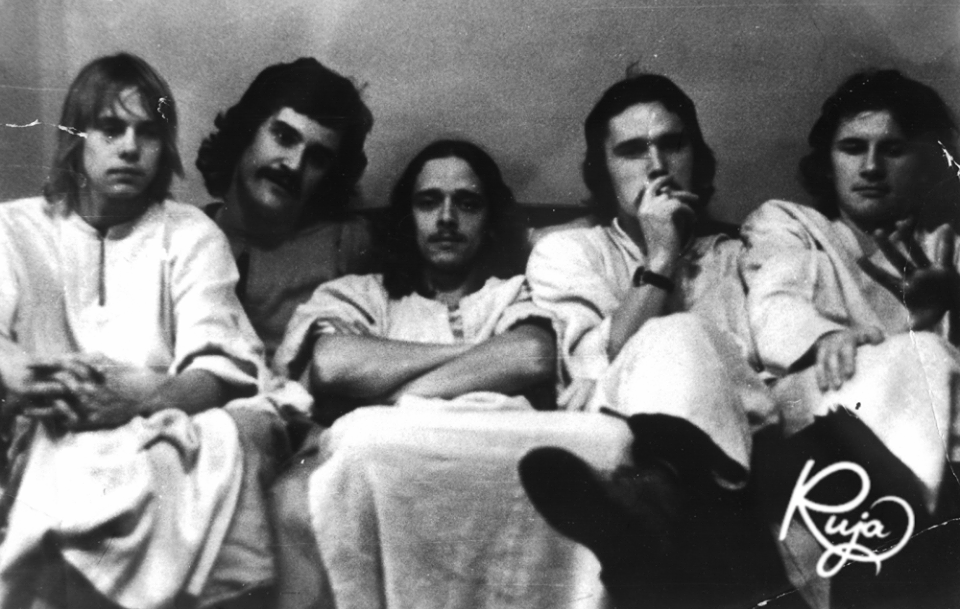

Yet one aspect of Estonian music that is not given enough attention neither in Estonia nor the wider world is Estonia’s contribution to progressive rock. Although the genre was particularly unfashionable in the 1990s throughout the world, under the media radar, prog has been experiencing an international revival led by neo-progressive bands like Porcupine Tree and Muse but also thanks to prog legends like Steve Hackett taking his Genesis Revisited performances across the world as well as bands like Yes who is currently on tour playing three of its classic 1970s albums. Because of this it seems high time for the Estonian music lovers to explore just how groundbreaking so many Estonian prog bands were. Just as Pärt’s music has won fans the world over, had Estonian progressive rock been granted the global exposure it deserved at the time, people would be amazed to see how a small country, at the time occupied by the Soviet Union, was producing music which was as good as any prog rock from outside of Estonia. Ruja, of course, is something of the jewel in the crown of Estonian prog. The virtuosity of multitalented musicians like Rein Rannap, combining with the voice of Urmas Alender, who was one of the best vocalists in any genre of rock music anywhere in the world, makes for unforgettable listening. At this same time artists like Sven Grünberg with his band Mess and, later, the short lived but highly musically complex Noor Eesti (a collaborative project between Tajo Kadajas and Rein Rannap) were all bands who could have easily got a major international record contract, had this avant-garde music been something the Soviet authorities had embraced rather than scorned and at various times officially prohibited.

Estonian creativity in this broad genre continued through the 1980s where In Spe found success with their ethereal symphonic rock. Other bands more inclined towards a jazz-rock sound included the wonderful Kaseke, and Radar. Linnu Tee’s early work saw Indrek Patte take prog into a new decade while also recording and performing in a resurgent Ruja. But it wasn’t just in progressive rock that Estonian music excelled at this time – Gunnar Graps produced a hard edged rock which still wins admiration across the former Soviet Union and Europe. The punk band Propeller, which again featured Alender, demonstrated just how versatile a vocalist he was excelling equally well in the varied styles of symphonic rock, pop ballads, punk and hard rock. The 80s also saw great success by the new-wave band Apelsin who I’d almost describe as an Estonian Talking Heads.

There are of course many more Estonian bands of the 70s and 80s whose music would surely delight people from around the world in addition to younger generations of Estonians. And this is why a museum of Estonian music is needed. Many capital cities are dotted with monuments and museums to various musical icons and Tallinn deserves no less. This proposed museum ought to cover all genres of Estonian music from traditional choral music to the present day. No period should be neglected, but certainly one special focus ought to be put on the period of the 70s and 80s as far from producing government sanctioned throw away music, Estonian rock was rebellious, highly original, musically delightful and most of it withstands the test of time better than a lot of Western European bands from the same period.

Additionally because of the difficulty of rock bands working with Melodiya Records (the only Soviet record label), a lot of the recordings of Estonian rock are difficult to find, although many of them have been released on CD and MP3 in generally pristine quality since the 1990s. Still though, as Europe’s leader in e-services, digitising as much Estonian music as possible and making it available online would help people discover a lot of Estonian’s hidden treasures.

Although music isn’t as profitable a business as it once was (not that in the USSR it ever was a “business” as such) creating a museum of Estonian music both in Tallinn and online would help raise Estonia’s profile internationally. Music is after all the universal language and the arts are one of the best ways to promote a culture globally.

In April 2014 Steve Hackett of Genesis returns to Estonia. He was one of the foremost international stars to play at the famous 1988 Tallinn rock festival. Although planning any project of this scope takes time, wouldn’t it be nice for Hackett to lay some sort of symbolic stone preparing the way for the museum? Even if it’s a digital stone, which in Estonia would be highly appropriate? I would hope that even in a time of economic austerity the project could get some support. Music is one public investment that I believe is always one worth making.

I

Cover photo: Ruja, courtesy of www.ruja.ee